Introduction

(Addendum to sentencing memorandum written by Assistant U.S. Attorney Sherri L. Schornstein)

A Florida drag racing entrepreneur with a history of alleged amphetamine use might seem an unlikely source of vital computer parts for major Pentagon weapon systems.

Over a four year period ending last year, however, Shannon A. Wren’s nine-employee company brokered the sale of more than $15.8 million in computer parts to government customers and others from a small office in a central Florida business park, including many items labeled as “military-capable” and destined for use in advanced fighters, radar systems, and missiles, according to government documents.

As Navy and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement investigators eventually learned, almost all of these parts were produced at a single factory in China, using inferior and recycled materials, while being falsely labeled as the products of well-known chip makers such as Intel, Texas Instruments, and Motorola.

Many have been seized, but any that remain in use pose the risk of causing “components to melt, burst, rupture, catch fire or explode, resulting in property damage, personal injury and death,” the government declared in U.S. District Court filing in Washington on Sept. 30. The Naval Air Systems Command, without addressing whether some of the counterfeit chips remain in use or circulation, had warned two weeks earlier that any failures had the potential to ground military aircraft or prompt mistaken shoot-downs of friendly planes.

Wren’s company, VisionTech – now shuttered as part of the first major federal effort to stop the trafficking of counterfeit computer chips to the U.S. military – flourished for years because the Defense Department has largely failed to impose significant controls on the origin and quality of the electronics it buys, according to federal investigators, industry officials, and lawmakers. Wren died in May at the age of 42, prior to his scheduled trial on federal charges.

Slow to act

Although the Pentagon is responsible for managing 4 million parts worth more than $94 billion, it has been slow to set a uniform standard for “counterfeit” items, track suspect suppliers, or require its contractors to confirm that the computer parts they purchase are genuine, according to a report last year by the Government Accountability Office.

Manufacturers of fake, knock-off chips in China, Taiwan and elsewhere are increasingly targeting the rapidly-growing market for “military-capable” computers in the United States, because the profit margins can be as much as 1000 times higher than in the civilian market, according to Brian C. Toohey, president of the Semiconductor Industry Association.

“The high value opportunities,” Toohey said in an interview, occur “in defense channels.”

Although the Pentagon has declared it is cracking down on fake parts, in recent months GAO investigators posing as chip brokers successfully purchased counterfeit circuits from Chinese suppliers that were labeled for use in military systems, according to a government official. The GAO acted at the request of Sen. Armed Services Committee chairman Carl Levin (D-Mich.) and the committee’s senior Republican member, John McCain (Ariz.), who became interested in the topic partly because a Commerce Department survey in January 2010 estimated the number of counterfeit electronic components detected by military contractors and suppliers more than doubled from 2005 to 2008.

Two months later, the GAO reported separately that:

- Counterfeit routers with high failure rates had been sold to the Navy,

- Counterfeit microprocessors had been sold to the Air Force for use on F-15 flight control computers,

- Oscillators with a “high failure rate” had been sold by a prohibited supplier for use by thousands of Air Force and Navy navigation systems. These failures “could prevent some unmanned systems from returning from their missions,” the GAO said without further explanation.

Obstacles to reform

McCain and Levin have both been critical of the Chinese government for failing to police its chip manufacturers, particularly those in the province of Guangdong. They attempted to dispatch three committee staff members there this spring, but China refused to grant them visas. “There is a flood of counterfeit parts entering the defense supply chain,” Levin told reporters on Monday. “It is endangering our troops and it is costing us a fortune.”

Levin and members of his staff said for example that counterfeit circuits made in China were recently used in a high-altitude Army missile meant to collide with incoming missiles, known as THAD, forcing repairs costing the government $2.675 million.“There’s no reason on earth that the replacement of a counterfeit part should be paid for by American taxpayers instead of by the contractor who put it on the system,” Levin said, adding that he and McCain intend to introduce legislation barring Pentagon reimbursement for such costs.

Levin also said that the staff had found counterfeit transistors were used in a radar system that Navy SH60-B helicopters – including some deployed in the Pacific — use to find targets at night. They were made in China and sold as scrap to a broker that in turn sold them to a Raytheon subcontractor, he said. “Raytheon did not know about the problem until the committee discovered it, and as a result, the Navy did not know about it either.”

Levin said he and McCain “fault the Pentagon for not enforcing the current law [requiring notifications to the government of any counterfeit parts], but the current law is inadequate.” A Pentagon spokesperson had no immediate response, and spokespersons at Raytheon also did not reply to a request for comment. Gen. Patrick J. O’Reilly, the MDA director, said Tuesday that his agency was working to find counterfeit parts before they were installed.

The 2010 Commerce Department survey faulted Department of Defense organizations, however, for failing to have “policies in place to prevent counterfeit parts from infiltrating their supply chain.” It also said that recordkeeping on counterfeit parts was poor and that “there is an insufficient chain of accountability” among government officials responsible for blocking their infiltration.

Many companies are reluctant to report the discovery of counterfeits because they fear it will damage their reputations, the survey concluded. Despite such risks, “the vast majority” of the chip brokers, distributors and resellers it surveyed were unwilling to take even modest precautions to protect themselves or their customers, relying on “visual inspections” of the parts they buy and sell instead of testing whether they meet government requirements, it said.

Only about a quarter of the Pentagon organizations attempted to assess the “business practices, past performance, locations, or facilities” of electronic suppliers before placing orders, the report added. “DOD is largely reactive, only identifying counterfeit parts and fraud after it occurs.”

Customs officials say that partly at prodding of domestic chip manufacturers they seized more than a million and a half counterfeit semiconductors at U.S. borders between 2008 and 2010. But the threat is rising, officials said. “Time and again, we’ve been bringing cases where individuals have taken counterfeit products and tried to sell it to our military,” Assistant Attorney General Lanny Breuer told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Nov. 1. He said “we need enhanced tools,” including stiffer penalties for counterfeiting.

VisionTech’s tale

Wren was indicted by the U.S. Attorney’s office in the District of Columbia in Nov. 2009 on charges of conspiracy and trafficking in counterfeit goods after BAE Systems and several other defense contractors complained about receiving faulty parts from him. Undercover federal agents also purchased two lots of counterfeit chips from VisionTech, located in Clearwater, Fla., the indictment said.

Wren, who according to court documents had spent time in drug rehabilitation, was a regular contender in Florida’s drag-racing circuit and owned a related clothing shop. But he evidently saw the potential for quick profit in brokering military-related chips, beginning five years ago: Within a short period, he had built up a customer list of 867 domestic firms and accumulated enough cash to spend $155,000 for a Ferrari Spider, $200,000 for a Rolls Royce, and to purchase a Bentley, more than 40 other vehicles, several houses, and a boat, according to court filings.

VisionTech’s website was not coy about the potential customers that mattered most: It featured a photo of a jet fighter. A phone recording claimed that “we have over 35 years of combined experience in the electronic distribution industry” and said the company specialized in name-brand circuits “as well as military components,” according to a transcript introduced in court as evidence.

The company’s phone recording further said “our value-added services include…in-house testing,” according to the transcript. But the company actually “did not employ an engineer or other quality control expert,” according to a plea agreement signed in Nov. 2010 by Wren’s top assistant at VisionTech, Stephanie A. McCloskey, who was sentenced last month to 38 months in prison for her role.

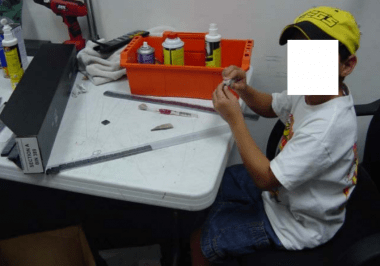

When prosecutors looked through the company’s computers, they found photos of unsanitary, sweat-shop production facilities in China as well as a picture of Wren’s young son – who was not charged with any offense – rubbing some of the Chinese-made chips delivered to Florida with Armor All, the fluid that brightens cars.

On 35 occasions, the parts VisionTech imported were so obviously fake that U.S. customs officials seized them at the borders, court records state. But Wren hired an attorney who asked that penalties be waived because the company “has never intended to purchase counterfeit parts.” These requests were approved on at least two occasions, according to court documents, when Customs agreed to eliminate one fine and reduce another from $124,530 to less than $19,000.

None of these shortcomings – in addition to Wren’s lack of experience and what assistant U.S. attorney Sherri L. Schornstein told a judge in February of this year was Wren’s habit of taking prescription amphetamines – prevented VisionTech’s sales of fake circuits to parts buyers for Raytheon Missile Systems, BAE Systems, and Northrop Grumman, among others. Wren claimed that he had been victimized by his Chinese supplier.

An uncertain fate for counterfeit parts

Raytheon said it bought 1,500 flash memory devices from a broker that purchased them from VisionTech, and that it planned to install them in the targeting system for anti-radar missiles used by F-16 fighters. Testing of some assembled circuits uncovered the deceit, a company official said in a letter to the court. BAE bought its parts through a broker for use in military aircraft computers that identify hostile planes; Northrop bought its parts through a broker for use in a ballistic missile defense radar program.

The Justice Department, in a press released accompanying its indictment of Wren and McCloskey, pointedly said it was not suggesting that the counterfeit parts Wren sold to these or other named, complaining customers “actually made their way into weapon systems.” But it was silent about the fate of parts sold to the hundreds of other customers.

Schornstein declined to be interviewed, saying through a spokesman that she could only confirm the information in court documents. But at McCloskey’s plea hearing, she said “we have not had an opportunity to trace the transactions – which number in the thousands in this case – to see whether we can identify if anyone was actually killed or injured.”

Read more in National Security

National Security

Pentagon whistleblower Franz Gayl is reinstated

Senior Marine Corps science advisor wins case, plans to return to work

National Security

Carrying concealed weapons just keeps getting easier

Ohio one of many states that have weakened requirements

Join the conversation

Show Comments