Introduction

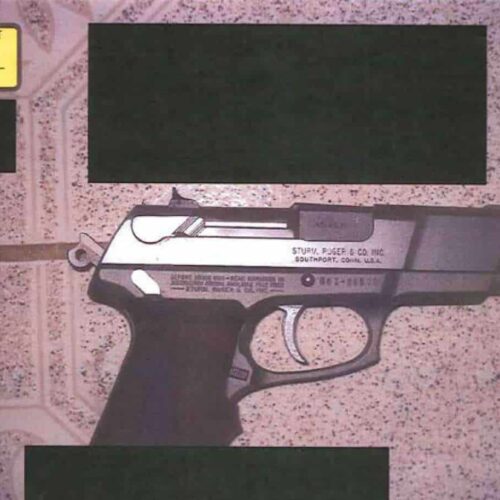

On Jan. 14, 2010, federal border patrol agents stopped two men driving a car through the border-crossing town of Columbus, New Mexico. Inside the vehicle was a cache of assault weapons, including AK-47s, Ruger .45-caliber handguns and pistols called “cop killers” because their ammunition can penetrate armor.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers ran the guns’ serial numbers in a nationwide database and waited. None of the eight came back flagged as stolen or suspect, so the agents let the men go — just a few short miles from the Mexican border, where gun trafficking is fueling a violent and deadly drug war.

At the time, the border guards were unaware that six of the weapons had been purchased by alleged straw buyers in a federal sting and were supposed to be monitored by Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives agents trying to bust a major Mexican gun running ring.

The ATF had not yet flagged the weapons in a law enforcement database, and CBP wouldn’t alert its sister law enforcement agency to the traffic stop for five months, delays that would prove fateful for both agencies.

The two men in the car turned out to be Blas Gutierrez and Miguel Carrillo, who earlier this month were indicted as part of a Mexican cartel gun trafficking operation that also involved Columbus’ mayor and police chief, court records show.

And one of the Ruger pistols from the vehicle turned up at a murder scene directly across the border in Puerto Palomas, Mexico, on Feb. 8 of this year, according to court records and a lawyer for one of the defendants.

The episode — confirmed by the Center for Public Integrity through interviews, internal agency memos and court records — highlights major gaps in the U.S. war on Mexican gun and drug cartels: America’s frontline agencies aren’t always coordinated fully and often feel powerless to arrest suspected gun runners in the absence of tougher federal laws.

As a result, weapons from an ATF sting in Arizona called “Fast and Furious” unwittingly ended up in the possession of a trafficking ring in a neighboring state while other guns crossed the border and at least one showed up at a murder scene in Mexico.

There has been an outcry on Capitol Hill and inside Mexico’s government since the Center and CBS News disclosed in a joint investigation earlier this month that ATF, over the objections of some agents, had allowed more than 1,700 guns over 15 months to fall into the hands of suspected straw buyers for Mexican cartels in hopes of making a bigger case.

In reaction to the controversy, the Justice Department recently issued a stern warning that agents must always interdict weapons headed across the border, even if it jeopardizes a criminal prosecution. In the Columbus case, a statement from the office of the New Mexico U.S. Attorney said that “every effort was made to seize firearms from defendants to prevent them from entering into Mexico, and no weapons were knowingly permitted to cross the border.”

But such statements are harder to implement on the front lines of the gun trafficking wars, according to agents, supervisors and prosecutors. James Cavanaugh, a former ATF commander, said stemming the flow of guns to Mexico is a Herculean task given the lack of law-enforcement resources and political will.

“I don’t see how it’s realistically going to slow down if we don’t make changes in resources, laws and policies,” he said. “It’s important because people are being slaughtered.”

Agents and prosecutors have been especially passionate in pleading for Congress to pass a specific law banning gun trafficking, and have repeatedly watched as courts threw out cases against straw buyers who made purchases that were technically legal.

The law ATF relies on most heavily to stop the flow of weapons south makes it illegal for someone to lie on a form at a gun shop, claiming to buy a weapon for himself when he or she is really buying it for someone else. Proving the person lied, however, is difficult and often judges treat the indiscretion as a paperwork violation deserving of light punishment, according to law enforcement authorities. Without a specific gun trafficking statute, authorities say, they often can’t do much as they watch suspicious activity.

“It’s upsetting,” said Michael Bouchard, ATF’s former assistant director in charge of field operations. “What are you supposed to do? No one in their right mind would let a gun go across the border knowing that it would kill a law enforcement officer or be used to kill others. But there’s no easy answer.”

The finger pointing and handwringing on the U.S. side of the border provides little solace in Mexico, where the victims of gun and drug violence pile up by the thousands as the numbers of guns trafficked across the border unabated grows by tens of thousands.

Last year, just in Ciudad Juarez, 3,111 people died in violence linked to illicit drug trafficking, according to Mexico’s National Security Council. Juarez, a city of about 1.3 million people, is the hub of drug trafficking in north-central Mexico. It is prized territory in a battle between the Sinaloa and Juarez cartels.

The victims of this war include one man in Palomas, a border hamlet west of Ciudad Juarez that has been hard hit by drug violence over the past year. The man lost his sister and brother-in-law in a spectacular shootout on Feb. 8. The brother-in-law, Alvaro Sandoval Diaz, had earlier shot three members of a Palomas street gang that had sought to extort protection money from his junkyard business. That incident brought Sandoval Diaz national attention; he was labeled “The Hero of Palomas” for standing up to powerful drug gangs.

His brother-in-law said that fame also invited the traffickers’ reprisal.

“You talk and you get in trouble,” said the long-time Palomas resident in a telephone interview. He asked that his name be withheld because the street gang implicated in the Feb. 8 murders remains active and he fears for his life. “If this was not a tragedy for our family, it would seem to me very comical how easy it is for guns to cross the border and take lives. It’s just too easy to get any kind of gun around here. We’re surrounded by guns.”

The attorney for Gutierrez, one of those indicted in the New Mexico case, said he was told by prosecutors that while a gun from his client’s car was found at a murder scene in Palomas on Feb. 8, it was a different murder.

The Columbus, N.M., incident marks a rare instance in which federal officials acknowledge guns from an ATF sting have crossed over to another crime ring, affecting a sister federal agency.

Spokesmen for CBP declined to comment on the stop. But they said agents cannot arrest anyone for smuggling guns into Mexico until they’ve entered the designated port of entry at the border crossing.

A spokesman for the U.S. Attorney in New Mexico also declined to discuss the case. The indictment left out details connecting that case to the Fast and Furious investigation, and did not even mention that CBP agents had stopped the car full of weapons. Instead, it simply stated the suspects had been observed with the weapons on Jan. 14, 2010.

Sen. Charles Grassley of Iowa, the senior Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, told the Center he has been investigating the Fast and Furious operation but has been unable to get any information from CBP on the January stop and the weapons check.

“We asked the Customs and Border Patrol to address this issue prior to a previously arranged briefing last week. However, the appropriate officials failed to attend the briefing, so we’re still waiting to hear from the agency about its involvement,” Grassley said Wednesday.

ATF documents state that the episode began on Jan. 9, 2010, when 23-year-old Jaime Avila Jr. allegedly walked into Lone Wolf Trading, a gun shop at a Glendale, Ariz., shopping center, and bought three FN 5.7 mm handguns — the ones known as “cop killers.” As required by law, the store reported the multiple sales of those handguns to ATF, and they were entered into a gun-tracing database on Jan. 11. Three days later, documents show, an ATF agent keyed the guns’ serial numbers into a different database of “suspect guns” that can be linked to the National Crime Information Center system tapped by all law enforcement agencies.

The entry notifies law enforcement agents to contact an ATF agent should they encounter one of these guns. Usually, officers will call the ATF agent on the phone from the scene and follow their directions.

The border patrol agents stopped Gutierrez and Carrillo because their vehicle matched the description of one reported stolen, said C.J. McElhinney, Gutierrez’s attorney. But the vehicle was not stolen and McElhinney said there’s nothing unusual about finding guns in a car in New Mexico.

“In New Mexico, everybody has a gun in the car,” he said. “It’s just the culture.”

Still, three of the guns in the vehicle had been bought by Avila and ATF was trying to track them. (The three AK-47s had been bought by another suspect in the Fast and Furious case.) But the computer entry for the National Crime Information Center system had apparently not yet gone through. Had the border officers contacted ATF, it would have signaled that guns in a sting operation had crossed state lines and were already near the Mexico border. Selling guns across state lines without a federal license is a crime.

Even if border agents had known the guns were suspect, says former ATF commander Cavanaugh, without more investigation into whether a crime had occurred, agents would not have been able to seize the weapons.

“Maybe I could go to a judge and ask for a warrant, but it’s going to be close,” said Cavanaugh. “You might have a de minimus charge, but that’s not going to stop a gun ring.”

On the other hand, had ATF known about the guns’ whereabouts earlier on it might have given a boost to the investigation, Cavanaugh acknowledged.

Later in the investigation, ATF stopped Gutierrez in Columbus twice and seized a total of 20 AK-47 pistols in his vehicle, on Feb. 12, and again on Feb. 24 of this year, according to court documents. ATF had nearly completed its investigation by then and was able to have Columbus Mayor Eddie Espinoza and Police Chief Angelo Vega indicted in the gun-running case.

The Fast and Furious case ended shortly after two guns in the sting were found in the vicinity of the fatal shooting of border patrol agent Brian Terry in Arizona on Dec. 14.

The trick in any investigation is deciding when you have enough to start making the arrests and a solid case, Cavanaugh said.

“Any decision you make entails risk of guns going across the border,” he said. “You’re trying to make it as small as you can.”

Read more in National Security

National Security

Weapons at root of trafficking case were subject of an earlier Center probe

National Security

The million-dollar weapon

Libya missile assault cost quarter billion dollars

Join the conversation

Show Comments