This story was published in partnership with The Arizona Republic and USA TODAY.

Introduction

ORACLE, Arizona — Thomas Benavidez never came home that Father’s Day.

His wife and three children knew he had to work, so they didn’t make plans to celebrate that Sunday. Instead, they spent it trying to confirm rumors of his death that swirled through this Arizona community of fewer than 4,000 people and quickly spread alongside details of a mining accident posted to Facebook.

Police photos from the scene show the flipped pickup truck Benavidez had parked in an open-pit copper mine in 2010. A 240-ton truck the size of a two-story house, designed to lug rock, drove over the smaller vehicle, flattening it. Benavidez, 52, was caught in one of the haul truck’s blind spots and crushed to death.

The mining industry has known for decades about these blind spots and the role they played in dozens of deaths. All the while, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) has pushed companies to install readily available and relatively cheap safety features that, it says, could save lives.

Mining companies and trade groups have responded with strong opposition.

A Center for Public Integrity review of MSHA investigative reports, police files and court documents reveals that weak oversight has mixed with mistakes at mines to deadly effect, as the industry and its regulators bicker over proposed rules. Various types of heavy machinery have directly or indirectly been involved in nearly 500 deaths, dozens of them caused by blind spots, at underground and surface mines since 2000, according to MSHA data.

A recent analysis by the agency found that 23 deaths could have been avoided in surface mines alone between 2003 and 2018 if heavy machinery were equipped with safety measures such as backup cameras, proximity sensors or other collision-warning systems.

Benavidez suffered one of those avoidable deaths when a haul truck driver, even after following the mine’s safety protocols, never saw Benavidez’s Chevrolet pickup and drove over it. A mechanic in the seat next to Benavidez was extricated from the vehicle, but with serious injuries.

“Think about having a million blind spots all around you,” Benavidez’s 30-year-old daughter, Amanda, said. “That’s what it’s like to be in one of those. You don’t know what’s right under you.”

The loss of a community linchpin

Benavidez — who went by “Eddie” or “Doughboy” — used to joke that when he died, he wanted a party, not a funeral. He was a John Wayne fan who named his sons, one of whom now sports a “Doughboy” tattoo, after characters played by the actor: Jake in honor of Big Jake’s titular character and Cole for El Dorado’s Cole Thornton.

“He was truly magnetic in every sense of the word,” read his obituary in a Tucson newspaper. The chapel in the rural town of San Manuel couldn’t accommodate the number of people who showed up to pay their respects. The crowd overflowed into the adjacent nursery, fellowship hall, courtyard and parking lot, where they listened in over speakers.

Benavidez had worked as a mechanic in the Ray copper mine, a roughly five-mile-long, open-pit operation between Tucson and Phoenix and owned by Asarco, a subsidiary of mining giant Grupo Mexico. Asarco saw a similar, potentially avoidable fatality in another of its Arizona operations in 2017. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

Nine years after his death, Benavidez’s wife, Nita, said she can’t understand why the haul truck wasn’t equipped with cameras and proximity-detection systems similar to the sensors in cars that beep when a driver drifts out of a lane or backs too close to another car. “They have them on our vehicles,” she said in an interview at her neatly decorated home off a short dirt road in Oracle. “Why can’t they have them on big vehicles that can’t see anything?”

Federal regulators have asked the same question for more than two decades.

“These large haulage trucks cost a fortune, but inexpensive camera systems which are currently available, are not required by MSHA,” Davitt McAteer, the head of MSHA during the Clinton administration, wrote in a statement accompanying testimony before Congress in 2007. “In the late 90s, I initiated a voluntary program to encourage operators to install them, and sadly that program has languished in the last several years.”

The first backup camera was unveiled on a Buick prototype in 1956, becoming common a half-century later. A federal regulation that came into effect last year made the devices standard on new cars sold in the United States but not on mining equipment.

A National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health study in 2007 noted that cameras had already been available for mining equipment for some time and were continuously improving.

While cameras are the simplest fix, more advanced collision-warning systems using radar, GPS or other tools have been developed to scan areas around operating heavy equipment. Proximity-detection systems, for example, can be modified to sound an alarm or automatically apply the brakes if they sense an impending collision. Studies show these tools are most effective when used together, especially because geologic conditions and other equipment in underground mines, such as dust monitors, can interfere with certain systems.

A single haul truck costs more than $1 million and can operate for decades, so companies are hesitant to pull them out of service. But retrofitting existing trucks with safety features costs at most a few thousand dollars, safety advocates say, an estimate that aligns with equipment available from online vendors. Komatsu, a heavy-equipment manufacturer whose trucks have been involved in some of the fatal mine accidents, sells retrofit kits, but a company spokeswoman would not disclose the price, saying it varies widely. Representatives of Caterpillar, another manufacturer whose trucks have been involved in collisions, did not respond to requests for comment, although the company has also developed blind spot cameras and sensors.

Don Lindell, Komatsu’s director of electric-drive truck technology solutions, said in a statement that the company and the industry need to reflect on blind spot fatalities. “Each accident, large or small, offers the mining community an opportunity to stop and learn. The biggest lessons can come from those tough moments,” he said.

Levi Allen, the international secretary-treasurer of the United Mine Workers of America, a major miners’ union, said that no single technology will remedy the blind spot problem. But he said the need to act has “been proven with bloodshed.”

“The time for proximity detection systems is now,” the union wrote in comments it submitted on a proposed rule in 2015 that would have mandated such systems in underground mines but was never finalized. “The industry must embrace this new technology to eliminate pinning, crushing and striking injuries and fatalities.”

Mining trade groups disagreed. “It is well-known that currently approved proximity detection systems are not perfect,” Bruce Watzman, the National Mining Association’s senior vice president for regulatory affairs, wrote to MSHA about that rule, adding that the agency was asking for it to be implemented too quickly.

A persistent problem

A study commissioned by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health found that haul truck drivers were unable to see a worker standing within 35 feet of the front of the truck. Views to the right and rear were almost entirely obscured. The 2006 study also found large blind spots on bulldozers, loaders, graders and other equipment.

Even at that point, blinds spots weren’t a new hazard.

MSHA first took on the issue under McAteer. In 1998, the agency considered proposing a rule to call for the use of cameras and early iterations of proximity sensors. In announcing the proposal, MSHA found that, between 1987 and 1996, 120 miners were killed and 1,377 were injured due to three main causes, one of which was “blind areas on self-propelled mobile equipment.”

McAteer said black-lung disease was the agency’s focus at the time, so he ultimately asked mining companies to “fix this as rational human beings” without a new rule mandating it.

A federal rule-making process can take years, as agencies propose updates to existing regulations and solicit comments from industry, the public and researchers.

When Joe Main took the helm of MSHA under President Barack Obama in 2009, the agency was able to finalize a rule that mandated proximity-detection systems in underground mines on continuous miners, which are machines equipped with a spiked wheel that eviscerates rock walls. During his tenure, MSHA also proposed the rule in 2015 that called for similar safety measures on other underground vehicles, but it languished.

Main said proximity-detection systems should be in use in both surface and underground mines, but some companies are “looking at their bottom line and not as much at the safety of their miners.”

David Zatezalo, a former chairman of the Ohio and Kentucky coal associations appointed by President Donald Trump to lead MSHA despite concerns over safety violations at a company he previously ran, has acknowledged the high percentage of mining deaths attributed to blind spots. Although this can be taken up at the state level — West Virginia, for example, enacted a related rule in 2017 — he said he thinks federal action is necessary on the matter.

On MSHA’s current regulatory agenda is a “request for information” on some of the same issues McAteer tried to tackle in 1998, which could result in a new proposed rule next year. But the agency ultimately answers to a president who signed an executive order calling for two regulations to be scrapped for every one adopted. An MSHA spokeswoman said the agency is moving forward with proposed rules as well as a safety initiative that communicates to companies the importance of collision-warning systems.

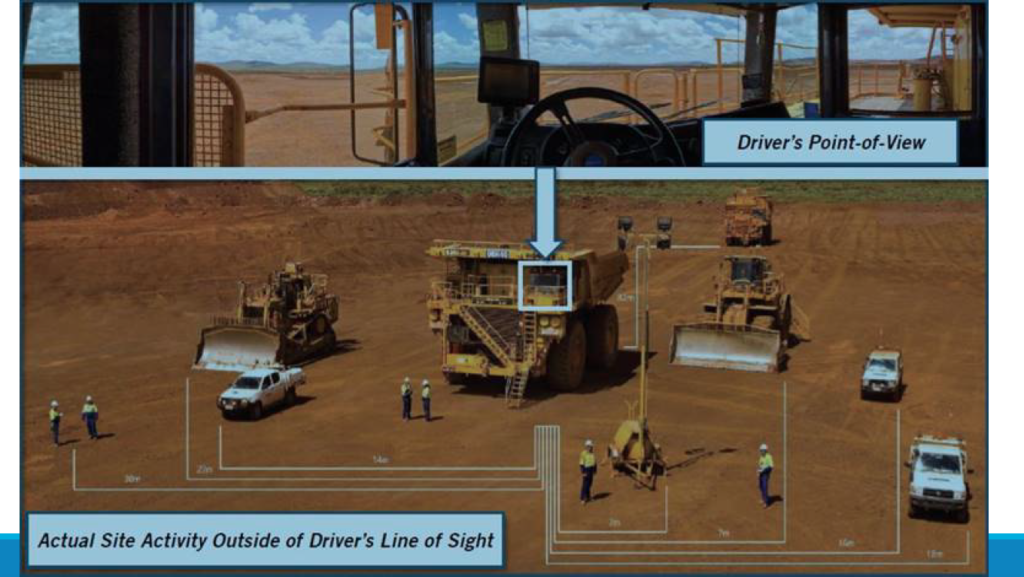

MSHA chief Zatezalo has recently given presentations to industry as well, during which he discussed the agency’s survey of avoidable accidents between 2003 and 2018. To illustrate the problem, he displayed a photo from a haul truck driver’s viewpoint showing what appears to be an empty area of a mine. A second photo reveals bulldozers, miners and pickup trucks surrounding the haul truck but obscured by blind spots.

Arizona saw three potentially avoidable fatalities during that period; only Nevada, with four, had more. In one Nevada case, a group of new hires was touring a gold mine in late 2017. A haul truck driver didn’t see them and crushed their van, killing two people inside.

In a Wyoming coal mine in 2008, a haul truck driver couldn’t see another truck parked in her rear blind spot. She backed into it, pinning the driver amidst his vehicle’s twisted metal. She comforted him as he went into shock. He fell unconscious and died at a nearby hospital hours later.

In February 2011, less than a year after Thomas Benavidez’s death, another tragedy struck Arizona’s mining sector, this time in the Kayenta Mine owned by Peabody Energy, the nation’s largest coal producer. A worker named Roy Lee Black, 55, was driving a diesel fuel truck in the strip mine when another miner driving a scraper didn’t see him until it was too late and their vehicles collided. Visibility was restricted by a high berm at an intersection, not a vehicle blind spot, but MSHA found several types of collision-warning systems potentially would have saved Black.

Black was trapped in his truck’s cab and engulfed by a fire that took two and a half hours and 33,000 gallons of water to extinguish. In its investigation, MSHA blamed Peabody and a construction company working in the mine, Skanska, for Black’s death, citing the companies for regulatory violations. The mine’s roadways lacked adequate signage, and the scraper had a known but unaddressed problem that distracted the driver. The agency’s investigation also found the manager on duty that day was not a certified foreman and a toxicology test wasn’t performed on the scraper’s driver after the crash, a breach of mine protocol.

A few years later, when MSHA proposed its proximity-detection system rule in underground mines, Peabody submitted a comment in opposition.

In a statement, Peabody spokeswoman Charlene Murdock disputed MSHA’s finding that Black could have been saved by collision-warning systems and said the company is conducting its own research on safety equipment.

“As part of our commitment to safety, we are testing surface collision avoidance systems and evaluating for future implementation,” she said.

Black’s family settled a wrongful death lawsuit against Skanska for more than $1 million. Workers’ compensation laws in Arizona and other states generally bar such lawsuits against direct employers, in this case Peabody.

“While fully cooperating with MSHA’s investigation, Skanska disputed MSHA’s citations,” the company’s spokesman, Mike Iacovella, said in a statement. He said that the company’s role in the mining operation was minimal and that MSHA later reduced the severity of the citations.

Industry opposition

McAteer blames the industry, particularly the politically powerful National Mining Association, for the lack of progress on blind spot deaths. “Rules can be stalled now by virtue of anything,” he said. “The association’s bread and butter is to stall. That is their whole reason for being.”

The association came out against proposed rules in 2011 and 2015 requiring proximity-detection systems on underground continuous miners and mine vehicles.

In recent, written comments, the trade group acknowledged that such systems could increase safety in surface mines and that some mining companies were using them. But it said more research is needed, and, in general, “rapid introduction of unproven technology can pose unforeseen safety risks.”

In a statement to the Center for Public Integrity, the association said it did not track the extent to which its members employed these safety features, although “safety is the top concern for mining companies.”

State mining associations also wield considerable influence. The Nevada Mining Association, for example, fought the same rules proposing the use of proximity-detection systems, saying the technology wasn’t advanced enough.

“Safety is the highest priority for the Nevada Mining Association and its members,” association president Dana Bennett said in a statement. But she said that retrofitting equipment is difficult because “third-party aftermarket devices have often been found to be complex and have unintended consequences that pose potential risks.”

The Benavidez family is tired of excuses. They still have relatives and friends working in mines and hope their family’s loss might lead employers to use available technology to protect workers.

But even that won’t bring back the man who used to have long talks with them over a fishing pole, who was seemingly always buying new tools for his latest project, who would hurry to help neighbors in need of a car repair.

It’s been nearly a decade since she lost her father, but Amanda still misses calling him every day after work to talk away the day’s stresses.

“He would just listen and laugh and make a joke and make it better,” she said. “I sometimes still pick up the phone and want to call.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments

I’ve been using Aircraft brand stripper for 20 years. It is the most effective and reliable product in my body shop for its purpose. I tried it the other day without this ingredient. It is the most useless stinky horrible stuff I’ve ever seen. I don’t know what this company is going to do now. They are definitely going to go bankrupt. I suppose it’s for the best , but what a bummer. Instead of spending 30 minutes stripping the old paint off of a hood, I spent three hours sanding it off and using tons of electricity and sandpaper.… Read more »