Introduction

Subscribe on Spotify | Google | Stitcher | TuneIn | Pandora | Apple Podcasts

Transcript

UNIDENTIFIED VOICES: From the Center for Public Integrity, this is The Heist.

SALLY HERSHIPS, HOST: We’re going to start today’s episode by getting to know one guy.

BOB CORKER: Hello. I’m Bob Corker. I hope you’re enjoying this holiday season.

HERSHIPS: A former Senator from Tennessee, Bob Corker.

CORKER: You know I never really dreamed I’d be a U.S. Senator. I dreamed of building a business.

ALLAN HOLMES: Let me tell you just a little bit about Senator Bob Corker.

HERSHIPS: Allan Holmes is editor of the Center for Public Integrity’s Tax project. He’s been following Corker for a couple of years.

HOLMES: He’s from Tennessee.

CORKER: Serving the people of Tennessee has been the greatest privilege of my life.

HOLMES: Grew up in Chattanooga.

HERSHIPS: He’s a Republican, solid, dependable.

HOLMES: Good soldier!

HERSHIPS: Corker is like a living stereotype of an all-American Senator. He was senior class president in high school. He was voted “best all-around boy” in his yearbook. In college, his frat brothers said he was the kind of guy who loved a good party, but never got super drunk. He started his own construction company, became mayor of Chattanooga, then, Senator.

HOLMES: During his career, he’s kind of considered a moderate. Huge deficit hawk. At one point he likened the deficit to one of the worst national security threats, more than even North Korea.

HERSHIPS: And it’s his take on debt, Corker’s status as a deficit hawk, that’s why we’re so interested in him in this episode. Because back in 2017, like we talked about in the last couple of episodes, Republicans were desperate to pass a new tax bill. Even though they controlled the White House, the Senate, and the House, they still didn’t have any big legislative accomplishments. Not one. The 2018 midterms were looming, and they needed a win to keep donors happy. And the tax plan, sure, it would rack up some debt — more than $1 trillion dollars. But all the Republican senators supported it — with one exception, Bob Corker.

CORKER: We’ve got to figure out a way to not just do the sugar side of this, but to do the spinach side. And I’m just going to tell you right now I see no evidence whatsoever, no evidence of us being willing to deal with the spinach side of the equation. So I think we’re in a hell of a mess right now, hell of a mess.

HERSHIPS: That sugar and spinach and stuff — just a few months after he said that, something big had changed. Corker, the famous deficit hawk, the guy who’d said that debt was more dangerous to the safety of the United States than North Korea, had agreed to pass the bill. So what happened?

Welcome to The Heist, a new investigative podcast from the Center for Public Integrity. I’m Sally Herships. While the administration promised its new tax bill would not add to the country’s debt, it did. Almost 2 trillion dollars. A trillion dollars has twelve zeros. That is so much money it’s going to take us generations to pay it back. But one powerful group did benefit much more than anybody else, from the new tax law — the rich.

Today on The Heist, what the passage of “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” tells us about how power works in Donald Trump’s America.

In 2017, Rich Prisinzano was working at the Treasury, in the Office of Tax Analysis. He’d worked as a tax analyst for thirteen years, through three administrations — George W. Bush, Obama, and now Trump. And what he loved about his job was the data. There was so much of it.

RICH PRISINZANO: I’m a numbers guy. I like to analyze stuff.

HERSHIPS: Analysis and numbers have been a lifetime obsession for Rich. When he was in the third grade, he got really into baseball. So he read a book about batting averages and statistics.

PRISINZANO: And it just described this other metric, he had come up with this other metric.

HERSHIPS: Was this a book for nine or ten-year-olds?

PRISINZANO: No, no.

HERSHIPS: So you’re this nine or ten-year-old who’s reading this book, which is probably written for like adult baseball fans.

Rich grew up to be the kind of guy who loves spreadsheets.

So what decisions have you and your wife made using spreadsheets?

PRISINZANO: I mean, our wedding planning was like one superduper spreadsheet because you know, you have like, is it plated? Is it a buffet? All this stuff and so you have to be able to compare them apples to apples.

HERSHIPS: Oh, for the catering?

PRISINZANO: For catering Yeah. Sorry, not to get I did not make a spreadsheet to marry my wife.

HERSHIPS: All this to say, Rich didn’t get into tax analysis because he loves taxes. Instead, he loves numbers. He sees them as a way to solve problems and to make decisions. So for Rich, taxes are like a really big puzzle.

At the Treasury, it was his job to run the numbers on tax proposals and try to predict what would happen if we implemented them. By the way, he was a career official, nonpartisan, so no one was rooting for any particular outcome. It was just straight math. But here’s what made it complicated, and kind of fun for a guy like Rich.

There are all these different economic levers economists and lawmakers can pull to try to get the federal budget to balance itself out. Stuff like expensing and interest deductions. And then on top of that, there are the tax codes — big, legal mazes that all affect each other and taxpayers like a game of Mousetrap.

PRISINZANO: When you do this, it sets off this other thing. And that leads to this consequence or when you do this, that changes this tax filer’s behavior and they’re going to do this.

HERSHIPS: Tax analysts also have to look for loopholes in the code, and predict how taxpayers might try to use them.

How excited did you feel when you realized, oh, cool, I’ve been through a couple of administrations like, we might do major tax reform, what was the level of excitement on a scale of one to 10? To use a number!

PRISINZANO: So I will confess that even through the summer, it wasn’t like guaranteed, right? So the excitement level was like seven or eight because it was still, it didn’t seem like it was going to happen.

HERSHIPS: But, it did. This bill was put together in a hurry. Remember, Republicans desperately needed a big legislative victory.

TRUMP: Thank you very much. You just want massive tax cuts. That’s what you want. That’s the only reason you’re going so wild.

HERSHIPS: Rich stuck around for awhile, but in late summer 2017, just months before the new bill was introduced in Congress, he left the Treasury. He had a new job. And that’s where he was watching all this unfold. He was working at the Penn Wharton Budget Model at the University of Pennsylvania. And he did almost exactly the same thing he’d done at the Treasury. He ran the numbers, to figure out what would happen. Here’s what Republicans said their plan would do. It was going to radically cut the corporate tax rate, lower personal taxes, close loopholes, grow the economy, create jobs.

And, the Administration had been selling the bill as revenue neutral. That means you cut some taxes, but take other measures to bring in more revenue, like closing loopholes or limiting deductions. In other words it all balances out. But when Rich ran the numbers at his new job, and his colleagues ran the numbers at his old job, they came up with pretty much the same thing. Projections showed the bill would add around $1.3 trillion to the debt. There are a lot of different estimates out there for how much the bill would add but bottom line, it is a big number.

So for a bill that set out to be revenue neutral for it to come in with a trillion dollars, is that unusual?

PRISINZANO: Yes. I think generally when we talk about being revenue neutral, there would be maybe 50 million, 100 million, 150 million, something that would be in what I would call, in the margin of error, but a trillion, it really wouldn’t be in what I would call the margin of error for revenue neutral.

HERSHIPS: Let’s stop for a second to think about that. The margin of error when you analyze a tax bill like this is gigantic. You can be off by as much as $50 to 100 million and still be within the margin of error. And even within a window that generous, with that much benefit of the doubt, Trump’s tax bill was coming in hundreds of billions of dollars over that number.

But instead of figuring out how to cut $1.5 trillion down, to balance it all out, to really make the tax bill revenue neutral, they moved the goalposts.

PRISINZANO: They changed from revenue neutral to it will pay for itself, which is a slightly different concept.

HERSHIPS: The idea now was the bill would cut taxes so much that businesses would reinvest, the economy would grow. And ultimately there would be more revenue for the IRS. In other words the tax cuts would pay for themselves. But Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin made an even bigger promise.

He said that not only would the bill pay for itself, it would generate so much revenue it would help pay down the United States of America’s existing debt. Here he is at a Washington D.C. ideas forum.

STEVEN MNUCHIN: Not only will this tax bill pay for itself, but it will pay down debt.

MAJOR GARRETT: And that pay for itself comes from that projected economic growth because you’re about two trillion dollars short, even when you look at your pay fors in the details released so far, at least according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

MNUCHIN: Yeah, I don’t think those numbers are right. I think it’s actually you know what we’re trying to achieve is $1.5 trillion static, OK? But that I would just describe as versus baseline. There’s about $500 billion between baseline and policy.

HERSHIPS: OK, this is wonky language, so Mnuchin gets into the weeds here, but basically what he’s saying is what we just said. That by cutting taxes enough, the economy will grow and the government will bring in more revenue.

To be clear, both Democrats and Republicans agreed it was time for tax reform. During President Obama’s administration, he’d also talked about lowering the corporate tax rate so that American companies didn’t take business overseas, where the tax rates were lower.

But of the many, many economists who analyzed the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — nonpartisan, conservative, and liberal — only one group said it thought the bill would work the way Mnuchin said it would. That it would actually pay for itself. That group was the Council of Economic Advisers, which is an agency within the executive office of the president. And that was the analysis Steven Mnuchin decided to go with.

MNUCHIN: So we think this tax plan will cut down the deficits, by a trillion dollars, that’s a large number.

PRISINZANO: You know, I was frustrated.

HERSHIPS: Rich kept hearing Mnuchin saying the tax plan would pay for itself.

PRISINZANO: Because, you know, again, as an economist, I think there’s general consensus it won’t. And it’s really frustrating to see someone ignore, you know, what I would call a consensus across a discipline.

HERSHIPS: So the consensus was this bill was going to create all this debt. But at the same time, Republicans were under all this pressure to get it passed. Remember Bob Corker, the guy who’d said that debt was more dangerous to the safety of the United States than North Korea. The guy who’d said there was no way he was going to pass this bill? At this point in the legislative process, Republicans needed his vote to move the bill forward.

Their careers were at stake. So on September 19, 2017, Mitch McConnell and Senator Pat Toomey put the squeeze on Corker.

HOLMES: What happened was that Senator McConnell called Corker and Toomey into his office.

HERSHIPS: Allan Holmes from the Center for Public Integrity again. We reached out to Bob Corker, Mitch McConnell and Pat Toomey, the only other senators who were there, and they all declined interviews. But Allan says McConnell’s office, in one of the oldest parts of the Capitol, would have set the tone for the meeting.

HOLMES: It has several rooms. It has all these very old oil paintings all around. It has this big fireplace over which is this kind of gilded edge, huge mirror. And so they settle in there to see if they can hammer out a deal.

HERSHIPS: To be clear we don’t know what happened. But here’s what we do know. They were in there for just ten minutes. And then, Corker walked out from behind those fancy doors. Corker, the man who’d sworn never to vote for this bill had changed his mind. Here he is on CNBC, not too long afterwards.

CORKER: Look, it’s something we need to do. You guys had this big campaign on CNBC years ago called rise above what it said was we needed to figure out a way to create more revenues, more revenues.

I look forward to this debate but Joe I think personally tax reform is harder than healthcare.

HERSHIPS: So with Corker’s vote the bill made it out of committee. Now it was ready to be voted on by the full Senate. But that’s not the end of the drama with Corker. Because a few weeks later, Corker had an announcement to make. He’d changed his mind, again. This time he would not vote for the bill.

Allan, what happened? From what we know, we know Corker had agreed to move forward with the bill.

HOLMES: Well he did. But being a deficit hawk, he wanted to make sure that this wasn’t going to add any more to the debt. So what he wants to do is put some type of guarantee in the bill that if for whatever reason, it doesn’t raise the types of revenue that everybody said it would, that something could come in and raise some taxes to make sure that it did.

HERSHIPS: That thing in the bill, that kicks in and guarantees that taxes would get raised is called a “trigger.”

HOLMES: And what happened, on the Senate floor was, they didn’t put it in. The Parliamentarian of the Senate said this can’t be put in for certain rules, and Corker wasn’t happy. He wasn’t happy at all.

HERSHIPS: But by this stage in the legislative process, Mtich McConnell no longer needed Corker. He now had all the votes he needed to pass the bill. At last, the Republicans were making progress — they were finally going to pass the tax cuts, a major piece of legislation. So when December 1, 2017 rolled around, McConnell was ready to rock-n-roll. He had some good news to share.

MITCH MCCONNELL: Hello, everyone.

HERSHIPS: While thirteen Republican senators struggled to fit on the stage behind him, McConnell adjusted the microphone on the podium in the White House press briefing room. He pushed his glasses up onto his nose.

MCCONNELL: Well this is, this is a great day for the country.

HERSHIPS: It was like watching someone get ready to blow out the candles on their birthday cake. And it looked like the senators behind him were dressed for the occasion. They were mostly in matching black suits and red ties. They were smiling and nodding and laughing at each other’s jokes.

(SOUNDBITE OF REPUBLICAN SENATORS LAUGHING)

HERSHIPS: It was the kind of press conference politicians dream of. The kind you only get once or twice every term if you’re lucky. The kind where you get to stand up in front reporters and TV cameras and say I’m about to do exactly what I promised.

MCCONNELL: I’ll take a couple of questions and then I assume you all have to file your stories and go to sleep.

HERSHIPS: In the meantime, you may be wondering, why, if there was a consensus that this bill would not work, were Mnuchin and so many Congressional Republicans working so hard to make it look like it would? Well, there’s a whole history around Republicans and tax reform. Especially this one big idea, trickle down, it’s the idea we talked about earlier that if you lower taxes on businesses and the rich, they’ll spend more, their businesses and bank accounts will grow from that investment, and ultimately they’ll end up paying taxes on their new, bigger incomes. More money for the government, more money for everyone.

But for Republicans, trickle down is way more than just economic theory. And I wanted to know where the idea got its start and why it’s so important.

Ok so I’ll introduce you in the piece. Why don’t you tell me how you’d like to be introduced?

MOLLY MICHELMORE: Ok, my name is Molly Michelmore. I am a historian, professor of American History at Washington and Lee University.

HERSHIPS: So I talked to Molly Michelmore. And she wrote a book called “Tax and Spend.” It’s all about how the U.S. develops its tax policies. She says the idea of trickle down goes way back to the time around World War I. It lost favor, it gained favor, but if the idea had a modern birthday it would have been born sometime after the Vietnam War era. The Democrats were losing major ground. Voters were upset — there was the war, civil rights. So the Republicans see an opportunity to swoop in and scoop up some voters.

MICHELMORE: But they have to figure out how to appeal to those folks who are increasingly disaffected from the Democratic Party, that is to say, the white working class, right, without alienating their core constituency in the business world. Without alienating rich people.

So how do you do that? How do you appeal to workers and to their employers at the same time? What Republicans hit on is trickle down, also commonly known as supply side economics.

MICHELMORE: And supply side economics because it basically promises a tax cut for everybody, it’s described as the politics of joy, it becomes the most popular because it’s the easiest to explain. Right, we are going to remove the shackles from the economy by cutting taxes.

HERSHIPS: Wait a second, did you say, so basically, trickle down became so popular during this era, because it was the easiest to explain?

MICHELMORE: Yeah. Right. So it doesn’t actually emanate from the halls of economics departments really, right. It does have an economist, professional economist associated with it. Namely Arthur Laffer, who is also involved and was also involved in crafting the 2017 tax bill. But it is largely promoted by what I would call sort of publicists rather than real kind of intellectual thinkers.

HERSHIPS: Arthur Laffer is what Molly calls a “renegade economist.” He came up with this concept called the Laffer Curve. It looks like a bell curve. And it seems to demonstrate the impossible, that if you lower taxes you’ll ultimately, somehow, increase tax revenue. Laffer drew this on a napkin supposedly when he was out at a bar with Dick Cheney and Don Rumsfield, way back in the 1970’s.

MICHELMORE: It’s on a cocktail napkin, right? There are no numbers here. But don’t worry. There’s a figure that goes along with this and everything oughta be fine.

HERSHIPS: This curve drawn on a cocktail napkin allows Republicans to say if we cut taxes don’t worry, we can raise more money for the government. This was the birth of the promise Republicans are still making today.

MICHELMORE: And this then allows you to say to people that are worried about debt and deficits, you don’t have to worry about this, right? We figured out the secret sauce, we figured out the kind of magic pill that will allow us to cut taxes, increase growth, and by increasing economic growth actually maintain stable federal revenues, allowing us to pay down the debt and deficit.

HERSHIPS: Does it work?

MICHELMORE: No. Never works, right? It never works.

HERSHIPS: How should I introduce you?

ARTHUR LAFFER: Dr. Arthur Laffer. I don’t know what you want to say. Economist from Nashville, Tennessee.

HERSHIPS: Okay. That sounds good.

LAFFER: I mean, you know, you want to put in my background with Reagan and with Trump and with the White House under Nixon and all that stuff. (fades out)

HERSHIPS: I had a chat with Arthur Laffer recently. And he was just like your goofy uncle, the one who cracks weird jokes but is really charmaring and has an answer for everything. And I sort of got how that cocktail napkin might have worked for some Republicans.

So what do you say to critics who say this just doesn’t work?

LAFFER: Well, let’s say the Laffer Curve obviously does work. I mean, no one disagrees with that. I mean, I don’t know of anyone now the implications and the application of it, and what the numbers are, they may disagree with the volumes, etc. If they really did disagree with it, they’re not very well- trained. Alright, they just don’t know math. But now where it applies and whether it does work or not, that depends on the circumstance. There are times when you can cut tax rates and lose revenue, and there are times when you can cut tax rates and gain revenues. And it depends upon this specific situation at hand.

HERSHIPS: But not all Republicans buy into the Laffer Curve or its economic cousin, trickle down. When he was running for president against Ronald Reagan in 1980 George H.W. Bush called trickle down “voodoo economics.”

So why do republicans keep sticking with this if it’s never worked?

MICHELMORE: I guess the question is, what do you mean, it’s never worked? Right? It has, in fact worked in terms of broadening the appeal of the party. And so as a political strategy it is incredibly successful.

If you want proof that trickle down doesn’t work Molly says just look at Kansas. Back in 2012 the state of Kansas had a Republican governor who tried out trickle down. Some businesses’ tax rates were slashed. And what happened? The state’s revenues cratered, services were drastically cut. Voters demanded the tax cuts be repealed.

MICHELMORE: And if I’m not mistaken, Kansas now has a Democratic governor.

HERSHIPS: She’s right. But Kansas or no Kansas, trickle down economics is still the cornerstone of Republican tax policy. And according to the theory, the tax bill’s trillion dollar deficit should just take care of itself. It’ll be cancelled out by all the economic growth the bill spurs. Well, one Republican didn’t buy that. And this is when we go back to the fall of 2017, to Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee. He’s where we left him — not on board with the tax bill.

CORKER: If it looks like to me Chuck, we’re adding one penny to the deficit. I am not going to be for it.

HERSHIPS: Corker had already announced he would not be running for re-election. In other words, it was like spring of senior year. His grades were in, he’d been accepted to the University of Tennessee. There was no reason for him to vote for this bill if he didn’t want to. He could ride off into the sunset, stick to his principles and stick it to Trump.

But that is not what happened. So what does Corker do? We’ll find out after the break.

(MUSIC)

PRATHEEK REBALA: Hi. I’m Pratheek Rebala, and I build tools that power our journalism at the Center for Public Integrity. One helped us identify legislation that lobbyists and corporations were pushing all over the country. These bills have allowed used car dealers to sell unsafe cars, they’ve limited access to abortions, and restricted the rights of protesters. And there are thousands of similar bills being shopped all the time impacting your life in ways that you might not even know. That’s why after we built the tool we made it available for anyone to use. That’s what we do at Public Integrity. To support the journalism we do, donate to Public Integrity at publicintegrity.org. With your help we’ll build more great reporting tools that will serve you and your community.

HERSHIPS: When Donald Trump was elected, it was the second time Rich Prisinzano had watched the changing of the guard from his job at the Treasury. The first time, in 2008 when Obama won, Rich says the election didn’t make a big difference in his day-to-day life. Again, as a career official he was nonpartisan.

PRISINZANO: When Trump took over, the transition was a very stark one. It was very much like, okay, Adam Looney and Mark Mazur, you’re not allowed back in the building, which wasn’t the case from Bush to Obama, there was a little bit of overlap.

HERSHIPS: Rich says people who’d been appointed by Obama were pushed out and not quickly replaced. They just weren’t there anymore. So it was up to Rich and his colleagues to try to explain to the Republicans in charge that this bill they had written, it was not going to pay for itself.

MARK MAZUR: Secretary Mnuchin kept pressing people in the Office of Tax Analysis to come up with the analysis that showed the corporate tax cuts pay for themselves. And they couldn’t, because that’s not what their analysis showed.

HERSHIPS: Mark Mazur used to work with Rich at the Treasury. He ran the Office of Tax Policy. Now he’s director of the Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center, a nonpartisan think tank. And he’s actually a pretty moderate guy — he’s one of the economists who explained to me that, yes, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did help some people in the middle class. But he also says there were also a lot of problems with it. And a lot of them stemmed from the fact that the bill was put together so quickly.

(SOUNDBITE OF PRESS CONFERENCE AT WHITE HOUSE)

A tax bill should take many, many pages to explain. But on April 26, 2017, Steven Mnuchin walked into the White House Press briefing room. He stood on the stage and presented the press with the Trump administration’s proposal. It was just one page with bullet points.

UNIDENTIFIED REPORTER: Obviously tax reform will be much more complicated. When will we see the details? When will we see the actual plan?

MNUCHIN: Well, we are moving as quickly as we can.

DAVID DAYEN: It’s almost like you know, you, you’re late on a book report and you have to tighten up the margins and increase the line spacing just to get a document that looks legitimate.

HERSHIPS: David Dayen is author of a critical biography of Steven Mnuchin called Fat Cat. You might remember him from the last episode. In addition to Mnuchin’s big promises about the bill, that it would mean more jobs and higher pay, Mnuchin also claimed that at the Treasury there were 100 people working on it.

MNUCHIN: We have over 100 people in the tax department looking at lots of different scenarios, and we’re working hard on that. We have no intention of doing something that would add trillions of dollars to the debt.

DAYEN: It was 500 words. And that’s what he passed off as this grand analysis of why the tax cuts would pay for itself. That is a level beyond. I mean, we’re used to people fudging the numbers a bit, but to claim that there was this massive study going on, and then to give a one-page document out to everybody, that that’s beyond the pale.

HERSHIPS: We tried to get an interview with Mnuchin for months. The Treasury never responded to that request but a spokesperson did answer some of our written questions. About Mnuchin’s claim that there are 100 people working on the plan, the spokesperson said yes, there are 100 employees at the Office of Tax Policy and at one time or another all of them were involved. And they said, quote, “Good policy is not measured by word count.” But, as Mark Mazur pointed out if you do some math — 500 words, 100 employees that comes out to five words per person. We also asked about Mnuchin’s claim that this bill would pay for itself. But the spokesperson didn’t answer that question.

A former employee from the Treasury who spoke to us on background confirmed what we said earlier, that the Trump administration was desperate to pass this bill. So much so that Mnuchin and other Republicans didn’t seem focused on the content — they were just doing whatever it took to get it through congress. This man is afraid if he’s identified he’ll lose his job. So the voice you’re hearing here is the voice of an actor.

ANONYMOUS SOURCE: Suddenly there was momentum, and the only thing that was important was passing something. There was a lot less concern about what it included, and there was more about passing it. The dynamic became just getting enough Senate votes. So every Senator became essentially a kingmaker. You know, every Senator then could ask for different things.

HERSHIPS: This source told me, at one point he was handed a list of talking points about what are called Opportunity Zones. They’re “economically-distressed” communities where new investments were supposed to get preferential tax treatment in the new bill. But the numbers he was given didn’t seem to add up.

ANONYMOUS SOURCE: We were getting a press conference together. And they handed me this list of talking points. And they said, well, we expect $100 billion of investment into opportunity zones. And I said, where are you guys getting that? What’s that from? They said, well, the Secretary said that and I was like, well, where did the Secretary get it? And they said, well, he just believes that and I was like, I’m not gonna say this. So they just, you know, they just pull stuff out of their ass.

HERSHIPS: By the way, those opportunity zones — let me just put it like this. The president of one firm, Skybridge Capital, which lets its clients invest in opportunity zones told Institutional Investor magazine last year, opportunity zones are like “high school sex,” “Everyone is talking about it, but nobody is doing it.” Even now, a year later the numbers are just a tiny fraction of what Mnuchin said they would be.

Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, and professor at Columbia University, describes the rush to get the bill out this way.

JOSEPH STIGLITZ: It was a group of pigs feeding at the trough. It was a frenzy. They wanted to get that tax bill out as quickly as they could, with the least transparency, so there wouldn’t be outrage from ordinary citizens. This is a real example of undermining democracy. We normally have processes of trying to make sure everything’s out and open and transparent. And the whole objective was to get it out quickly before Americans realized what was going on.

HERSHIPS: Democrats didn’t get a copy of the bill until the day they had to vote on it. The same day as Mitch McConnell’s press conference. They were furious.

JON TESTER: Tonight we’re going to be voting on the tax bill.

HERSHIPS: That’s Senator Jon Tester, a Democrat from Montana. He posted this video on Twitter. The House had passed its version of the bill and now it was the Senate’s turn to finalize its version and then vote.

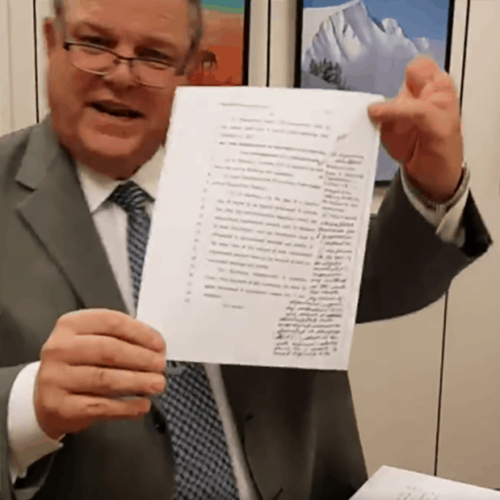

TESTER: I just got the tax bill 25 minutes ago. This is the tax bill. See how thick it is?

(SOUNDBITE OF TESTER DROPPING BILL)

HERSHIPS: That’s Tester dropping his copy of the bill on his desk — it’s almost 500 pages long. And it looks like an essay you might have turned in in high school and just gotten back from your teacher. There are all these paragraphs crossed out and handwritten notes in the margins.

TESTER: Can you tell what that word is? If you can, you’ve got better eyes than me! This is unbelievable.

HERSHIPS: Unbelievable or not, the Senate passed its version of the bill. So back to Bob Corker. He was the only Republican to have voted against it, but it wasn’t a done deal yet. The bill still had to be reconciled with the House version of the bill, and then the Senate would have to vote on it one last time. But as that vote approached, Corker, the man who’d spent his career talking about the dangers of debt, changed his mind, again. For the third and final time.

UNIDENTIFIED NEWS ANCHOR: Senator Bob Corker of Tennessee now a yes on the tax bill, remember, he was the lone Republican holdout.

CORKER: Do I think our country is better off having this tax reform in place versus not? I do.

HERSHIPS: Corker took that final vote on December 20, 2017.

He declined our interview request to talk about why he changed his mind. But there was one theory floating around — his critics said he changed his mind because of what they called the “Corker Kickback.” A provision added late in the game that included tax cuts benefiting some real estate holders, possibly including Corker’s own family. He denied the rumor.

Allan Holmes at the Center for Public Integrity says we’ll never really know what happened. But he does think that for Corker this was about being a good soldier. Playing along with the Republican party.

HOLMES: You know, he’s out of office now. He could say whatever he wants. And he has nothing to lose, but I think he’s still a very loyal Republican.

HERSHIPS: On December 22, President Trump signed the final version of the bill into law. Then, he jumped on a jet to Mar-a-Lago, and the shiny new tax bill went back to the Treasury Department. It was now time for a team of lawyers to write regulations, to figure out how the bill was actually going to work.

As for Rich he felt like he’d come up with numbers in good faith and kept politics out of his analysis. But the numbers had been ignored.

PRISINZANO: And so, you know, for somebody who, that was my one shot. And I didn’t, I didn’t have as much of a direct impact as I would have liked. And, you know, in 30 years, I hope not to be working on tax anymore.

HERSHIPS: In April of 2018, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office released an estimate — the new tax law would add $1.8 trillion dollars to the debt.

Almost exactly what Rich and his colleagues had been projecting since the fall of 2017. We can’t get into Bob Corker’s head, so it’s impossible to know what he was really thinking. But after all that debate, after all his back and forthing and all the drama and the news coverage, Corker had voted for the bill. And here it was doing exactly what he had said he wanted to avoid, creating trillions of dollars of debt. So, if you were him at this moment in time there’s a good chance you’d be thinking, oh crap.

Here he is at a Senate Budget Committee Hearing in April of 2018 — it would be his last year as a senator.

CORKER: You’ve talked about the cost of this tax bill. And if it ends up costing what has been laid out here, it could well be one of the worst votes I’ve made. I hope that is not the case. And I hope there’s other data.

HERSHIPS: In that statement the Treasury Department sent us, they claim the 2017 tax law benefited American families, lower income Americans, small businesses and working families.

And it is important to point out that the new tax law did do some good. Here’s Mark Mazur again.

MAZUR: Lots of lower income people may have benefited from a slight increase in the child tax credit.

HERSHIPS: Imagine a “ladder,” where the people making the most money are at the top, and the people who make the least are at the bottom. Mazur says, as you climb down this ladder, one rung at a time, the number of people who benefited from the tax cut gets smaller and smaller. So yeah, at the bottom, some low-income households did qualify for a slight increase — for example, the child tax credit. They saved money there. But several income rungs up, a much larger percentage of really rich people were getting tax breaks on estate taxes and corporate taxes and individual taxes.

MAZUR: And so there are sort of benefits throughout the income distribution. But the largest benefits went to the highest income individuals.

HERSHIPS: And don’t forget this bill cost a lot of money.

MAZUR: You know, it’s more than a trillion and a half dollars of additional debt added to the, you know, the credit card of the United States. And to the extent that gets paid off in the future is essentially what you’ve done is provided a tax cut to people today and have it paid for by you know our kids and grandkids.

HERSHIPS: And I guess if we were going to take, if the country was going to do something with $2 trillion, if you were gonna spend $2 trillion, you would want a return on it?

MAZUR: No, exactly. Right. That’s exactly the right way to think about it. (fades out)

HERSHIPS: Mark says there are probably dozens of examples. We could get return on investments by having better roads, better ports, better airports.

MAZUR: Or you could take that money and invest in education. Or improved healthcare or research on things. There’s probably no shortage of things you could have invested in that have a higher rate of return than what we’re gonna get from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

HERSHIPS: There is no shortage of fierce critics of Trump’s tax bill. We wanted to find someone in the Administration to defend them. As I mentioned, we tried to get an interview with Steven Mnuchin, many times, but we only got those written responses from the Treasury. But, luckily for us, Kai Ryssdal, the host of Marketplace, interviewed Mnuchin at UCLA back in 2018. And he asked him everything I wanted to. You should know though that Mnuchin got really heckled by the crowd there. He got booed and hissed.

MNUCHIN: Just let me ask you because I’m a little new, do you guys hiss as much at your own questions as you do at the moderator’s questions?

KAI RYSSDAL: We’re gonna find out.

HERSHIPS: Mnuchin was standing behind a podium, all by himself. He had his clasped behind his back and he did this thing he does when you might imagine he’s nervous — he kept half puckering his lips like he was trying on lipstick and jutting his head forward and back.

RYSSDAL: You and the President and the Congress passed last year.

HERSHIPS: Ryssdal asked Mnuchin how the tax bill would pay for itself.

RYSSDAL: During your confirmation hearings, you said whatever tax reform the Trump administration was going to work on will not add to the debt and the deficit.

MNUCHIN: It’s true and I stand behind that.

(SOUNDBITE OF HISS FROM AUDIENCE)

RYSSDAL: Sir, the tax bill that’s enforced now adds a trillion and a half dollars to the deficit.

MNUCHIN: No. That’s not the case. The tax bill, scored on a static basis, adds a trillion and a half. Let me just go through the numbers.

RYSSDAL: Yes sir.

HERSHIPS: He asked about how some companies gave one-time bonuses instead of raises.

RYSSDAL: 250 companies have given one-time bonuses. And I guess the question is, what would you rather have? Would you rather have a one time bonus or a consistent wage increase?

MNUCHIN: We fundamentally believe that there will be wage increases going.

RYSSDAL: Why do you believe that?

MNUCHIN: We believe that there is more opportunity.

HERSHIPS: And about trickle down.

MNUCHIN: To create that. And, you’re correct. It is stimulus, but it’ll be paid back.

RYSSDAL: How so?

MNUCHIN: Again, I just said. If you look at OK, 35 basis points of growth.

RYSSDAL: Three tenths of one percent on the GDP?

MNUCHIN: Correct.

RYSSDAL: And that’s going to do it?

MNUCHIN: That’s absolutely right.

RYSSDAL: Even though no tax cut in history has paid for itself. Not the Reagan tax cuts. Not the Kennedy tax cuts. No tax cuts have paid for themselves.

MNUCHIN: You obviously have an opinion that you’re trying, and it’s different than my opinion.

RYSSDAL: No sir, those are facts.

MNUCHIN: No. You have an opinion.

HERSHIPS: Even a kid in the audience asked about all the debt the bill was going to create.

AUDIENCE MEMBER 1: My generation will have to pay off $1.4 trillion in debt. And the tax bill will also lead millions to lose their health insurance. How can you live with this?

(SOUNDBITE OF AUDIENCE APPLAUSE)

MNUCHIN: Well, since you are so incredibly eloquent, what grade are you in?

AUDIENCE MEMBER 2: Answer the question!

MNUCHIN: I’m going to answer the question. Give me a second. (fades out)

(MUSIC)

HERSHIPS: The Trump Administration promised Americans that it would cut taxes. It also promised that ordinary Americans would benefit.

To say that Republicans didn’t deliver on those promises isn’t totally accurate. They did what they said they would do — they cut some individual income taxes and gave corporations the biggest tax cut in American history. But they were wrong about what happened next. The tax cut was not a win for the middle class. In fact, the middle class will be paying it off for generations to come. CPI’s Allan Holmes again.

What does the passage of this bill say about how power works in Donald Trump’s America?

HOLMES: The wealthy are in charge and it doesn’t matter what good policy is. It doesn’t matter what people who are experts in writing policy that would be the most effective and efficacious. What speaks is wealth.

What speaks is access to power. Who gets to talk to the Trump administration? Who has Steve Mnuchin’s ear? It’s not the factory floor worker. It’s not the teacher. It’s not the person working at McDonald’s. It’s the people at Mar-a-Lago. It’s the people who he does business with, who they do business with.

HERSHIPS: America was promised a tax bill that would benefit all Americans. But instead, we got a bait and switch. The country got stuck with a deal that worked out really well, mostly just for the very rich. And the rest of us got left the bill. And that, is the heist.

(MUSIC)

Next time on The Heist, corporations scored big with the new tax law. But what about the workers?

DEBORAH VOLPE: If it’s a dollar I was never supposed to have I’m grateful, I’m blessed, it’s all good, right? But where is the rest of this going?

ARNE ALSIN: I knew what they were going to do with this cash, which is send it away, away to the stock market for buybacks.

HERSHIPS: Our episode today was reported by me, Sally Herships, Allan Holmes, and Peter Cary. It was co-written by producer Sarah Wyman. Our editor was Curtis Fox, with help from consulting editor Alison MacAdam and Center for Public Integrity’s Tax Project editor Allan Holmes. We had production help from Lucas Brady Woods, Brett Forrest, Camille Petersen, and Ali Swenson. Our theme music and original score by composer Nina Perry and performed by musicians Danny Keane, Dawne Adams, and Oli Langford. Our engineer is Peregrine Andrews. The Heist is executive produced by me and the Center for Public Integrity’s Mei Fong.

Join the conversation

Show Comments