This story was co-published with TIME.

Introduction

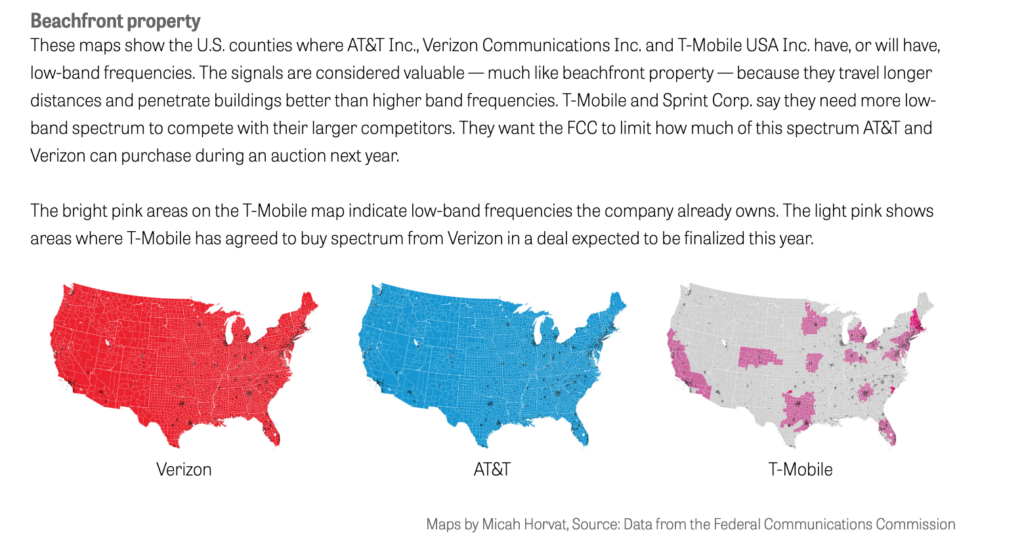

When the federal government auctions off a huge swath of airwaves early next year, it aims to give wireless carriers more capacity and also increase competition in an industry that is now firmly in the grips of AT&T Inc. and Verizon Communications Inc.

It will likely deliver on the first goal, but analysts suspect it won’t on the second.

On July 16, the Federal Communications Commission will vote on exactly how the auction for so-called low-band spectrum will play out. The airwaves, in the 600 megahertz range, are highly coveted because they travel long distances and penetrate buildings, characteristics needed to build a nearly seamless nationwide wireless network.

AT&T and Verizon, the nation’s two largest carriers, already own 73 percent of low-band spectrum, so they provide much more coverage than Sprint Corp. and T-Mobile Inc., which own a negligible amount. More coverage has allowed AT&T and Verizon to sign up about two-thirds of all wireless customers nationwide.

Sprint and T-Mobile say they need more low-band spectrum to better compete, and the upcoming auction, scheduled for the first quarter of 2016, may be their last chance for decades to get a big chunk of it at one time. That’s why they asked the FCC to create a reserve of spectrum that only they and other smaller carriers can bid on.

AT&T and Verizon said no limits should be placed on the auction.

The four companies spent tens of millions of dollars trying to convince Congress and the FCC to see things their way. They paid not only for traditional lobbying but also for academic studies, Astroturf public relations campaigns and opinion articles by hired experts to influence lawmakers, regulators and the public, according to a Center for Public Integrity investigation. AT&T and Verizon vastly outspent their smaller rivals.

The rules the FCC will consider Thursday set aside 30 megahertz that can only be bid on by carriers that don’t have a dominant presence in any given market.

That typically will rule out AT&T and Verizon from bidding on most of the airwaves in the reserve — but not all. The reserve represents 42 percent of the 70 megahertz of low-band spectrum many analysts expect will become available. The auction, however, depends on television stations agreeing to sell spectrum they hold licenses for, and more could be available if a larger number of broadcasters choose to sell.

Some analysts say the 30 megahertz reserve may not be enough to ensure more competition.

“Ideally it should be more,” William Ho, principal analyst at 556 Ventures in Reston, Virginia, said in an interview.

The spectrum comes from frequencies currently controlled by television broadcasters, which are voluntarily selling their licenses.

If the buying power of AT&T and Verizon is limited too much, Ho said, broadcasters may avoid selling their spectrum because they believe they won’t get a premium price. That would depress the amount of money the FCC collects from the auction.

Harold Feld, a senior vice president at Public Knowledge, a consumer advocacy group in Washington that supported a larger reserve, said the set aside “isn’t aggressive enough.”

Feld said carriers need to buy spectrum in 20 megahertz chunks in a market to support the amount of traffic traveling on their advanced networks. A 30 megahertz reserve will therefore only help T-Mobile or Sprint, not both. With AT&T and Verizon likely being able to purchase 20 megahertz blocks of non-reserved spectrum, the auction may end up benefiting just three carriers. The FCC and the Justice Department, when it blocked AT&T’s purchase of T-Mobile in 2011, said it takes at least four companies to keep the wireless industry minimally competitive.

The smaller carriers won’t be able to match AT&T’s and Verizon’s buying power for the remaining spectrum, analysts predict.

“We have had a strong commitment to having four-firm competition, which is why we have done things like keeping T-Mobile and Sprint from merging,” Feld said in an interview. “But these [auction] rules actually support just three-firm competition, not four. Why?”

The Justice Department, in an FCC filing last month, lobbied the FCC to set aside more spectrum for small carriers. The FCC should “give considerable weight in determining the amount of spectrum included in the reserve to protecting and promoting competition,” wrote William Baer, assistant attorney general for the department’s Antitrust Division.

The Justice Department also said it is concerned that AT&T and Verizon will buy up spectrum even if it has no intention of using it just to keep it out of the hands of Sprint and T-Mobile, and reduce competition.

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler defended the reserve last month, calling it “a revolutionary decision” that the agency has never before committed to.

“The important thing is that it exists,” Wheeler said. “That there exists, for the first time, a set aside, a reserve, to make sure that there is the capacity for a quality of competition among wireless carriers. That’s the key point.”

In the end, the question of how large a reserve there should be will become moot if the FCC can convince a large number of broadcasters to sell their airwaves, especially in the largest markets, said Reed Hundt, FCC chairman in the Clinton administration. He believes more than 70 megahertz will be available.

As much as 120 megahertz could go up for sale, he said, which will give T-Mobile and Sprint the opportunity to buy more spectrum. With that much spectrum on the market, AT&T and Verizon likely will find it hard to buy it all up, Hundt said in an interview.

“There are a number ways the FCC can get to that number,” he said “At that point, the problem disappears.”

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Broadband

Cell phone lobby win means ‘more people will die’

Industry pressure leads to watered down 911 location rules

Broadband

White House report says lack of competition barrier to broadband adoption

New report details ways to use existing programs to expand usage

Join the conversation

Show Comments