This story is published in partnership with Belt Magazine and is part of a series supported in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Introduction

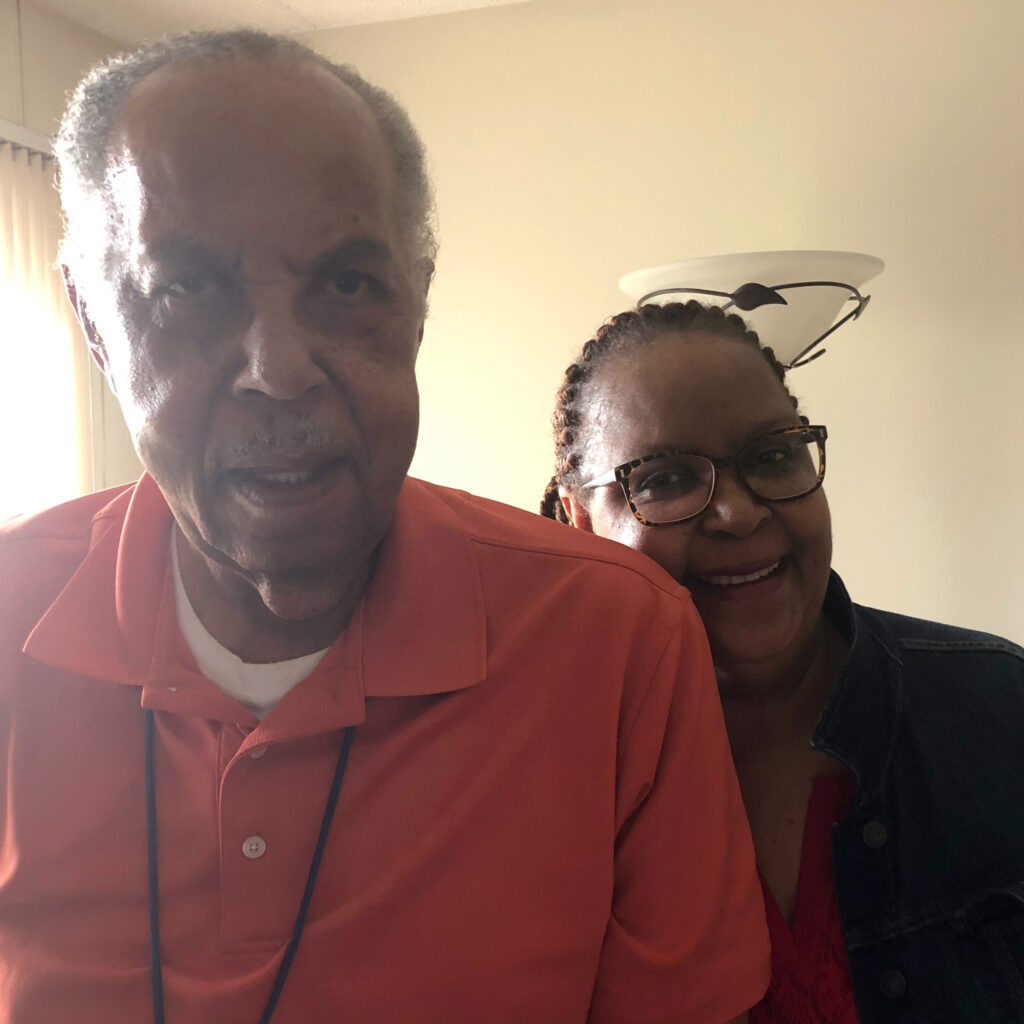

In the winter of 1946, Perkins Pringle boarded the first leg of a 950-mile train ride from Durant, Mississippi, to Akron, Ohio—the Rubber Capital of the World. He initially stayed with his Uncle Erich and found work at the twenty-five thousand-acre Ravenna Arsenal, which stockpiled ammunition and machinery during World War II. Eight years after his arrival, he ended up at Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. in the sooty mill room where workers mixed raw rubber with carbon black, or lamp black, which made tires strong and dark. He then moved to the tube room, the rubber shop, and eventually the tire tread shop, making it a point to learn every job there within six months.

It was hard work but a good living for laborers like Pringle who toiled at Goodyear, B.F. Goodrich, Firestone, General Tire, and other factories in the Rubber City. “The last couple of years at Goodyear, I made $100,000 a year,” Pringle, who retired in 1979, told me when I spoke with him last year. The Pringles “had everything that everyone else had,” as one of his daughters put it. They were able to move from the Valley off Euclid Avenue in West Akron to a three-bedroom corner house on Orlando Avenue up on the Hill. The Pringle children who wanted to attend college were able to do so, and the eldest son is now a lawyer.

Having everything that everyone else had also meant breathing the same air, drinking the same water, and experiencing some of the same resultant health conditions. In those days, soot filled the Akron air; residue covered workers, their cars, homes, and churches. It smelled like rotten eggs from the sulfur dioxide, particularly near the factories on the east and south sides of town. The water had a hint of the same to some people’s taste. Some residents welcomed the sulfuric stench, calling it the smell of money, prosperity, jobs. But today, the smell has also become associated with disease and death.

Of course, factory workers were the most directly affected. But their families were also exposed to the chemicals on their work clothes, in their hair, under their nails and penetrating their pores. And those who somehow had no family ties to the rubber industry were still at risk, because everyone drank the same water and breathed the same air—especially if you lived or attended school in the shadows of the smokestacks, or near landfills where rubber companies dumped liquid and solid waste.

Pringle, now ninety-one, believes he has experienced both the immediate and latent effects of chemical exposure. “I had lung surgery in ’68,” Pringle recalled. “I had fluid leaking out of my lungs.” At one point, he spent a year at the Edwin Shaw Sanatorium, named after a Goodrich executive, for what doctors thought was tuberculosis. “They didn’t find out what was really wrong with me until 1986,” he told me. “It was asbestosis.” He was later diagnosed with COPD and mesothelioma. And he wasn’t the only one. Back then, it seemed to Pringle that rubber workers were becoming sick not only at his job, but all over town. “It fell on everybody all at once,” Pringle said. “They thought they were dying from lamp black and all that stuff.”

Like Pringle’s children, I grew up in Akron. My paternal grandparents lived behind Firestone. My stepfather, uncles, neighbors, and lots of other people I knew were employed in the rubber industry. I remember the sooty skies, and I have never forgotten that smell. While it serves in one sense as a reminder of my childhood and Akron’s heyday—when anyone who wanted to work could make good money with little to no experience or education—it also made me wonder what was really lurking in the air and water.

The jobs that a whole generation of Akronites held are mostly gone, but the health effects of the toxins they worked around every day still linger. Some illnesses are just now surfacing, and, if the findings of epigenetics and toxic exposure studies are any indication, they could keep doing so for generations. This is the story of how all of that came to pass—the rubber, the factories, the jobs, the pollution, the sicknesses—and how it continues to shape the lives of people and families in Akron and beyond.

The history

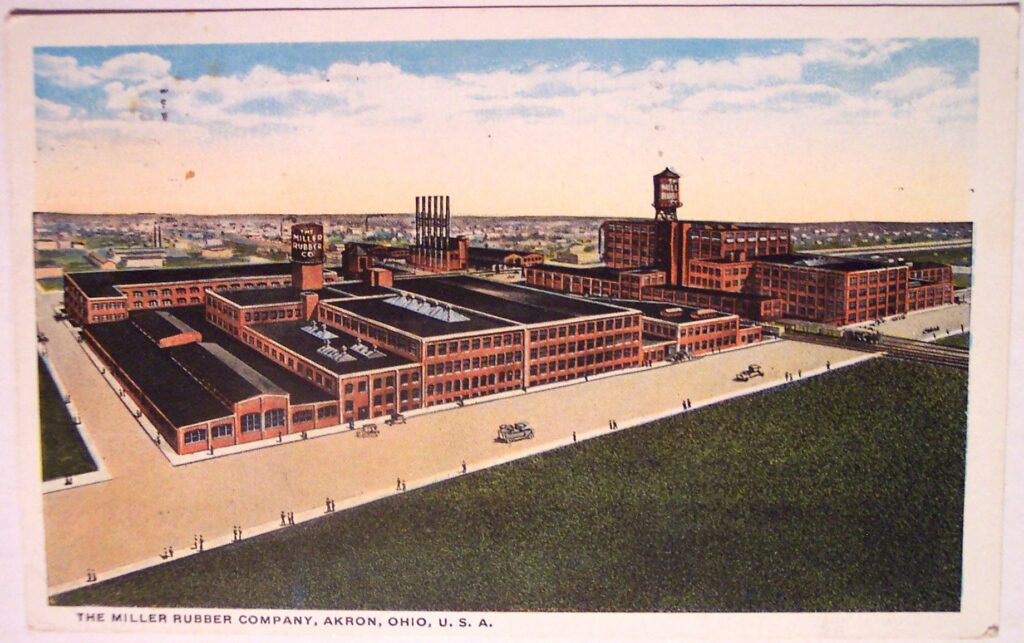

Akron’s rubber industry dates back to 1870, when Benjamin Franklin Goodrich secured local loans to relocate his business from Melrose, New York, according to Steve Love and David Giffels, authors of Wheels of Fortune: The Story of Rubber in Akron. The company was later incorporated as B.F. Goodrich in 1880. Brothers Frank and Charles Seiberling started Goodyear in 1898, Harvey S. Firestone moved from Chicago to set up shop in Akron in 1900, and William F. O’Neil started General Tire in 1915. Their companies became known as the Big Four.

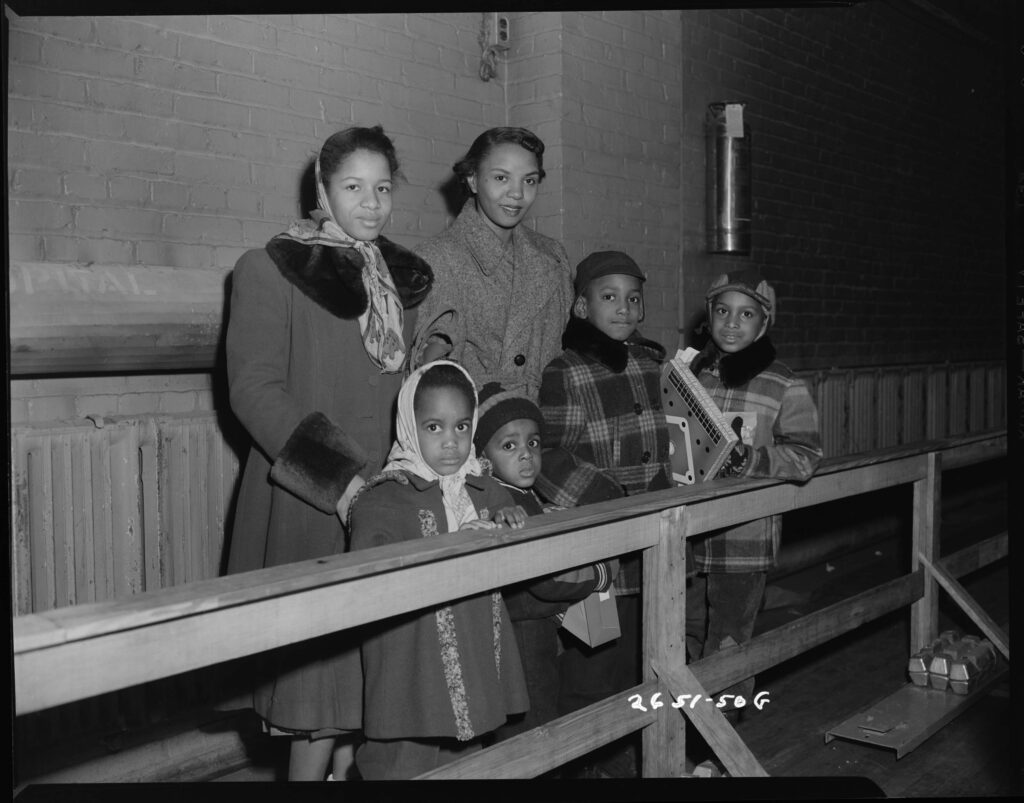

In the early 1900s, Akron was one of the nation’s fastest-growing cities. It literally put America on wheels, manufacturing most of the country’s tires and earning the title Rubber Capital of the World. So many people flocked here from Appalachia that West Virginians claim their three Rs meant reading, ’riting, and the road up Route 21 to Akron. African Americans left the deep South for Akron in response to heavy recruitment by factories during the World Wars, and then in greater numbers during the Great Migration. From the outset, women worked in the factories, which made everything from rubber bands to hoses in addition to tires. According to the historian Kathleen L. Endres, this was especially true of “war wives.”

By the ’60s, however, the rubber industry showed visible signs of ailing, and it went on life support during the ‘70s and ‘80s. The list of contributing factors was long—recalls, takeover attempts, corporate greed, the spike in gas prices from the oil embargo of 1973, union demands, foreign competition, and the introduction of the radial tire, which not only lasted longer, but also could be used year-round, ending the need to purchase and swap out winter tires. In just seven years, the rubber industry flatlined, despite controversial concessions by unions to keep the companies alive and their members employed. Between 1975 and 1982, one by one, the Big Four pulled the plugs on production of passenger tires in Akron, later relocating to the South or being absorbed by other corporations.

Akron died a little bit, too.

Over the decades, tens of thousands of people lost jobs. The rubber industry is no longer a fail-safe option where sons and daughters could follow their parents into the plants or offices. Following the passenger tire shutdown, unemployment hit ten percent in June 1983 and again in October 2009 during the Great Recession, based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. And although overall jobs increased about three percent for the greater Akron metropolitan area from 2002 to 2014, they dropped ten percent for the city itself, according to a 2017 report on post-industrial strategies from the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

To revive itself, Akron turned its attention toward polymers and attempted to diversify its economic base, even snagging a coveted Amazon fulfillment center. But the city has been unable to turn back the clock on deindustrialization. That’s apparent in the boarded-up businesses, vacant lots where families used to live, death of two major shopping malls and warnings not to venture in previously safe neighborhoods when the sun turns in for the night. The trickle-down effect of plant closings and job losses has cut the population by a third, from a high of 290,351 in 1960 to 197,023 in 2020, according to the U.S. census.

As the rubber industry declined, its toxic effects began to reveal themselves. “What’s important is that for most of the chronic diseases caused by occupational toxins, they don’t appear for twenty to forty years after first exposure,” said Steven Markowitz, MD, who co-authored a 1991 study linking ortho-toluidine to bladder cancer at Goodyear Chemical in Niagara Falls. Richard Clapp, senior environmental health scientist for the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production at the University of Massachusetts, said, “It takes so long for some of these cancers to develop that we may still be seeing what’s left from legacy exposures.”

The Akron area is a microcosm of deindustrialized regions across the country, as well as communities where manufacturers relocated to take advantage of cheaper labor, tax breaks, and the opportunity to build more modern facilities at lower costs. Each area has a laundry list of occupational toxins unique to local manufacturing processes. They also have chemicals in common such as benzene, which has been associated with leukemia, and another carcinogen known as trichloroethylene (TCE), a volatile organic compound that can affect the immune and central nervous systems, liver and kidneys.

In addition to asbestos-related illnesses and various types of cancer, medical research has shown links between industrial toxins and respiratory problems such as asthma, emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); auto-immune conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), lupus, or sarcoidosis; reproductive issues; and even heart disease and diabetes. “A lot of times people think diabetes is all about behavior, but there’s lots of burgeoning research showing that it’s actually often related to these metabolic disruptors that are in our air and the other parts of the environment,” said Kelly Ard, PhD, associate professor in the School of Environment and Natural Resources at The Ohio State University and faculty affiliate at OSU’s Institute for Population Research in Columbus.

A number of these health conditions appear in my family tree. My stepfather and almost all of my uncles were rubber workers. My stepfather died of lung cancer at the age of forty-two, when I was in the ninth grade. Two more of my uncles had cancer, and so did my mother, biological father, grandfather, grandmother, godfather, stepmother and two aunts. Two siblings have auto-immune conditions. One suffers from MS. The other has fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and a thymoma, a rare tumor of the thymus gland under the breastbone. The tiny gland typically shrinks by puberty after it stops producing T cells and simply turns into fat. This one didn’t.

Like my paternal grandmother, with whom we lived when I was born, I had severe asthma. Between infancy and the fourth grade, I ended up in Akron Children’s Hospital for pneumonia three times. That’s why loved ones still wring their hands every time I have the flu, bronchitis, or even a little cold. Asthma struck one of my cousins even harder. She spent a year or so of her childhood five states away at a respiratory hospital in Denver for pulmonary rehabilitation. But it was the pancreatic cancer that took her out in her early fifties. Another cousin has sarcoidosis, and one has ankylosing spondylitis, which inflames his spine and temporarily turned his eyes scarlet.

Many families have similar health histories. Some have been able to connect the dots—medically and legally—to the rubber industry, as in the case of a multimillion-dollar asbestos settlement involving thousands of workers in 2012. Others are still scratching their heads about “patterns” of illness among their family and friends or wondering about disease clusters in their communities. They never knew about the various medical studies conducted on the rubber industry over the years, but no matter. Their instincts and experiences are proof enough to them that these are more than coincidence.

Take the Carson family, for instance. “My father worked for a regional rubber company, RCA Rubber Co., for a little more than twenty years before being forced into retirement when he developed multiple sclerosis,” Phillip Carson told me. “Later, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and lymphoma. My father’s youngest brother also worked at RCA for a long time and eventually developed lymphoma…Both my father and uncle eventually passed away due to the lymphoma. I don’t know of anyone else in my father’s family—ancestors and extended family—who ever had any kind of cancer, so I’ve always thought it was odd that two siblings out of eleven had developed the same cancer while working at the same company.”

“So I’ve always thought it was odd that two siblings out of eleven had developed the same cancer while working at the same company.”

Phillip Carson, whose father worked for RCA Rubber Co.

The 2020 mortality rate for cancer in the United States was 158 out of every one hundred thousand people, according to data from the National Cancer Institute and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The death rate for cancer in Summit County has dropped, but still exceeds national levels at 172 for every hundred thousand residents, according to the Ohio Department of Health’s 2019 report. That number has dropped slightly. During regular tire production, from 1950 to 1979, the rate averaged 183 per hundred thousand people in Summit County. It ranged from 142 for white women to a high of 248 for non-white men.

Just as only a percentage of smokers end up with lung cancer, not everyone exposed directly or indirectly to industrial toxins will develop health problems, Dr. Markowitz explains. The reasons are pretty much the same in both cases: susceptibility, heredity, and/or level of exposure. The ironclad connection is for mesothelioma, a type of cancer that only comes from exposure to asbestos, and for angiosarcoma of the liver. “Those are the two we call sentinel occupational cancers,” Clapp explained. “If they occur, there’s probably some type of exposure at work.”

A number of studies found elevated rates of cancer among rubber workers in Akron, from skin cancer to stomach cancer. One study consistently observed higher than expected cancer deaths across a range of departments at B.F. Goodrich, including processing, tire building, and curing. The analysis looked at death certificates with cancer as the cause of mortality for 13,571 white male employees who worked at Goodrich for at least five years. The men died from leukemia and a range of other types of cancer: stomach, intestinal, lung, bladder, brain and lymphatic. The study, published in the American Journal of Epidemiology, covered a thirty-six-year period.

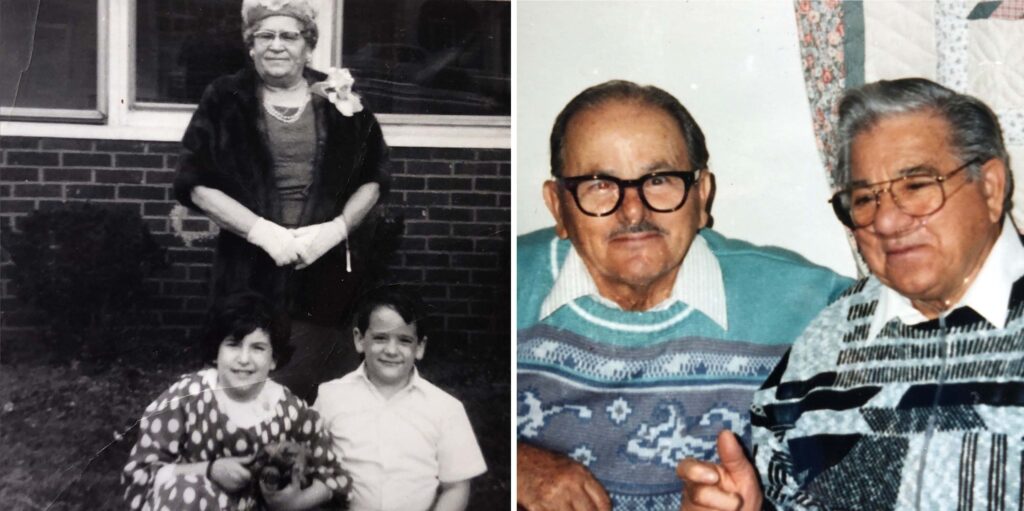

Dennis Paonessa knows of roughly thirty people who have had cancer, including his maternal grandmother and younger brother, Dean, who died of leukemia at the age of seven. “He was probably two when we found out,” says Paonessa, who was about nine years old at the time. Dean was conceived during the sixties when their father, Guido, was making tires at Goodyear. It was tough for Paonessa as a child, watching his younger brother suffer. He had a similar experience caring for his grandmother, Theresa Ciccarone, who had colon cancer in her late sixties. “She only had it for two years before she died,” he recalled. “That’s a hard way to go.”

Ciccarone had emigrated from Italy to Sharon, Pennsylvania, and moved to Akron around 1920, when her husband got a job here. She worked at the Ravenna Arsenal during World War II and then at B.F. Goodrich with rubber bands when more women started working at plants. Like his grandmother, Paonessa worked on the sprawling campus of B.F. Goodrich for ARA Food Services, now known as Aramark, while he was studying business at the University of Akron. “You could walk through any building and go from one end to the other without going outside, so you’re breathing in the same air that they make tires with,” he said.

Paonessa has liver and gall bladder problems, as well as Barrett’s esophagus, which has been associated with toxic exposure and can lead to esophageal cancer. His father, Guido, who never smoked, developed COPD during his time at Goodyear. Paonessa doesn’t know for sure whether his ailments or those of his family members are connected to their jobs. He suspects that they are, especially after poring over medical research on rubber industry toxins and pollution. “I’ve been to a lot of doctors and a lot of hospitals,” he said. “It’s like they don’t want to commit to that kind of stuff. …Unless you pin them down, they’re not going to say, ‘Well, we see the connection.’”

Robert D. Giles’ doctors never figured out why he developed COPD and a “mild” case of sarcoidosis. Giles says that he has no family history of respiratory or auto-immune disease. He thinks his illnesses could be connected to the rubber industry, but he isn’t sure. His conditions could also be related to his three-year stint in the Army in Nuremberg, Germany; or possibly to his childhood in Appalachia, where his father developed black lung disease from working in mines near Bristol, Virginia; or later to growing up on Bell Street near Goodrich in Akron; or maybe a combination of all of the above. Such is the mystery that many people in industrial areas face about their ailments. “I had a whole lot going against me,” Giles says.

Giles started working at Goodyear in 1965. Then twenty-seven years old, he started out building tires just before they were cured. In the early ‘80s, he became one of the first Black supervisors at the urging of a union rep. Five years later, he switched to stock preparation and then to computer operation. “I was one of the fortunate ones, because they usually didn’t let blacks run the machines back then,” Giles recalled. He was also fortunate to survive the rubber industry’s mass cutbacks, retiring in 2001 at the age of sixty-two. “It was okay overall,” Giles says of his time at Goodyear. “It made a good life for me. I was able to raise two kids and live comfortably.”

Still, he acknowledges that he fared better than a number of his peers, especially other African Americans who disproportionately worked on the front end of the tire production process, where they encountered more exposure to chemicals and soot—toxins they also brought home to their families. Race is a clear factor when it comes to exposure and illness. In Akron, as is the case across the country, toxic industry was — and is — concentrated near areas with high African American populations, with the exception of factory-built neighborhoods such as Goodyear Heights and Firestone Park, which initially had covenants barring non-white homeowners. Black people bore — and bear — the brunt of industry’s negative effects, including disease and death.

Take-home toxins

Atha Walker blended huge vats of rubber and additives in a Banbury mixer at the Seiberling Rubber Company in Barberton, Ohio, adjacent to the southwest side of Akron. Walker joined Seiberling in the fifties when African-American men weren’t welcome in factory showers. While rubber employees of all backgrounds periodically left plants wearing their work clothes, Black men had no choice for many years. So, day after day, Walker came home from work wearing striped gray coveralls covered with soot.

“His clothes would be totally black,” said his youngest daughter, Judi Walker Miles. “He would clean out his nose and cough every day, and you’d see black soot come out. It’s amazing that he wasn’t ever seriously ill. It almost seems like he was a medical marvel, because a lot of younger men got sick. He would talk about how they had to leave, and they were concerned about how they’d be able to provide for their families.”

Walker, who lived to be ninety-four, had rheumatoid arthritis and pernicious anemia, which interferes with the body’s absorption of vitamin B-12 needed to produce blood cells. Miles, who is now a lawyer in Cleveland, developed asthma and a half-dozen autoimmune conditions, including scleroderma, which is associated with rubber chemicals such as benzene, trichloroethylene (TCE), toluene, xylene and vinyl chloride. She also has lupus; fibromyalgia, a neurological chronic pain syndrome; and vasculitis, which inflames the blood vessels in her temples. She believes the take-home toxins on her father’s work clothes, along with local pollution, contributed to these conditions.

Certain industrial toxins can cause illness in the immediate relatives of factory workers (through secondary exposures) and in local residents (through air and water pollution) — particularly if they have no family or medical history of the health conditions and there is no other identifiable cause, according to experts I spoke with and existing studies. “There are take-home exposures to dust, like when the worker brings their work clothes home and children play on the worker’s lap or spouses shake out the clothes before they put them in the washing machines,” Clapp explained.

“I have a full life. But it’s not the life I expected to have.”

Judi Walker Miles, who suffers from health problems. Her father worked at the Seiberling Rubber Company

Like Miles, three of Pringle’s four daughters have suffered from ailments they believe to be linked to secondary and environmental exposure to industrial toxins, since they have no family or medical history of their conditions. “It’s almost synonymous to secondhand smoke,” said his youngest daughter, Pamela Pringle Wellington. “That’s how I look at it.” One sister has fibromyalgia. Another has multiple cancers: ovarian, breast, colon, liver and kidney. Wellington underwent surgery to have cancerous cells removed from her colon cancer. She also has a multiplier effect of medical problems stemming from polymyalgia rheumatica, an auto-immune condition with arthritic symptoms that forced her to use a wheelchair, walker and cane in her fifties. It also led to her being among the fifteen percent of PMR sufferers who develop temporal arteritis, which damages arteries to the brain.

These days, nerve pain jolts parts of Wellington’s body, and she has experienced TIA mini strokes, or transient ischemic attacks. During the winter, she wears a scarf or wool cap inside her home, because cold air makes the left side of her head hurt. That’s on top of the debilitating headaches that strike without warning. Plus, she gained nearly a hundred pounds at one point from the prescribed steroids. “I had been dealing with it maybe five years before I was diagnosed in October 2013,” said Wellington, who had to retire early from the job she loved at the University of Akron as a senior payroll specialist. “I lost my vision three times, so I am blessed that it came back.”

Research on auto-immune connections is not as extensive as the research on cancer, but a number of studies have associated auto-immune diseases with occupational toxins and pollution. According to 2007 research published in Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience, a number of toxins have been linked to negative impacts on the central nervous system, including trichloroethylene (TCE), aluminum, arsenic, inorganic and organic mercury, lead, manganese and thallium. The researchers obtained health histories from NIOSH on nine hundred workers who had experienced direct exposure to the toxins through their skin or inhalation. The study found that workers often spread the toxins to their families from residue in their hair or on their clothing. The researchers also discussed the complexity and reality of cumulative exposures or “multiple chemicals from multiple sources” — like combining take-home exposure with exposure to air and water pollution.

Despite the research, Judi Miles and other patients I spoke with told me that doctors rarely, if ever, broach the possibility of their illnesses being connected to the rubber industry. In the meantime, Miles said, her health problems have led to three miscarriages, at which point her doctors told her it would be dangerous to have children; a year after having a hysterectomy based on that advice, Miles said she met a specialist and pre-eminent researcher who told her that she might have been able to conceive after all. She was crushed, but said she tries to focus on the bright side: her two blood clotting disorders, Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and Post-transfusion purpura (PTP), have been in remission for almost seventeen years.

“I have a full life,” Miles told me. “But it’s not the life I expected to have.”

Children are particularly vulnerable

Glistening white snow, speckled with tiny black flakes — I grew up thinking this was normal. Soot was part of everyday life in Akron and some of its industrial sister cities. It covered laundry, seeped into windows, and blanketed cars. The soot left the stones of St. Vincent de Paul Catholic Church, in my grade-school parish, as black as the ashes crossed on our foreheads at the beginning of Lent. An exterior cleaning in 1997 revealed that the Romanesque Revival-style church is really the color of off-white sandstone. So is St. Bernard’s downtown, where I had piano lessons with Sister Catherine. I grew up thinking that both churches were naturally black as coal.

Children are particularly vulnerable to the effects of pollution. Toxins in the air can reach and affect children in myriad ways. “They sit on houses, and they settle in places where children can touch them and get in their mouth,” said Ard, the Ohio State researcher. “They’re undergoing development … so they metabolize things faster,” she explained. “It has long-term implications for their health, their mental abilities, for impulsivity, for all sorts of social issues later down the line.”

In the early ’80s, a team of researchers at the University of Akron conducted a two-year study to assess the effect of air pollution, like soot, on children. They found that students who went to school nearer rubber plants were exposed to significantly more pollution than students just a few miles away and reported a daily symptom twice as often: sore throat, runny nose, coughing, chest congestion or irritated eyes. They also experienced more cases of acute respiratory illnesses, including greater airway and air flow obstruction. These were the healthy ones; the study excluded students who had already been diagnosed with chronic conditions such as asthma. Either way, researchers said the students faced a greater risk of lung disease later in life. Today, those children would be in their early fifties.

In addition to respiratory problems like asthma, studies and anecdotal reports indicate children are at risk of developing ailments from exposure to toxic chemicals in the womb. A 2018 research review noted the association of chemical pollutants such as trichloroethylene to birth defects and infant mortality across the United States and in other countries. This included congenital heart defects, skin problems, neural tube defects and other conditions affecting the central nervous system. The researchers, whose work was published in the journal Environmental Prevention, wrote that “pregnant women and the developing fetus are particularly sensitive to the effects of environmental exposure.”

Another source of concern for some parents is recycled tire crumb rubber, which appears on playgrounds and athletic fields in Ohio and around the country. In 2016, multiple federal agencies, including the EPA and the CDC, began jointly researching the issue. They released a 2019 report that describes some of the chemicals in the recycled rubber on synthetic turf fields, but cautioned that the report is not a risk assessment. In 2019, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, which is among the participating agencies, surveyed parents in preparation for its risk assessment of playgrounds; in the survey, parents said that twenty-five percent of the playgrounds they visited most often had rubber surfaces.

That same year, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of American ranked Akron as one of the top twenty “asthma capitals” in the country—a designation based on prevalence, emergency department visits, asthma-related deaths, and risk factors such as air quality—and number fourteen on the Top 100 Most Challenging Places to Live With Asthma, behind Dayton (number two) and Cleveland (number five).

I reached out to the remaining tire companies, inviting them to discuss specific details about occupational health and the impact of industrial toxins on local residents. General Tire was sold to Continental, and B.F. Goodrich no longer exists (though tires are still sold under both brand names). Firestone declined to comment. Goodyear sent a statement: “We have policies and procedures in place focused on material handling and the safe use of substances used or stored at our facilities. Preventing work-related illness in the workplace begins with understanding the potential impacts of noise and the substances used in the manufacturing process. We assess workplace exposures through monitoring, which validates that controls are effective and provides transparency to associates.”

For richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, Akronites have stood by the rubber companies. Some people shrug their shoulders and say that at least the city’s industrial prime was good while it lasted. Most people I talked to spoke fondly of the Big Four, the jobs and prosperity they offered. After all, these factories provided a means of trading up houses and trading in cars—American made, of course—every three to four years. And some families still live proudly in the homes that rubber magnates built for them in Goodyear Heights and Firestone Park, noting that their neighborhoods’ corporate namesakes still maintain ties to Akron in some form or fashion.

Those in this camp will often describe the loss of jobs, health, and lives as “unintended consequences.” But others have no nostalgia about the rubber companies, nor the sulfur dioxide and other chemicals they emitted into the air. “I’m looking at the positive, but I’m also looking at the negative,” Perkins Pringle’s youngest daughter, Pamela Pringle Wellington, said of the rubber factories. “Dumping into the water, the smoke and whatever was emitted into the air—we were inhaling that. …I’ve often wondered if they knew what was going on.” (Pringle himself, who suffered from COPD and mesothelioma, died just before publication due to complications from COVID-19.)

Goodyear is the only rubber company whose headquarters remain here, anchoring East Market Street in the shiny new and slightly gentrified East End. Its golden Wingfoot logo adorns the Cleveland Cavaliers’ burgundy uniform, an emblem of pride on the chests of native son LeBron James and his teammates in 2016 when they brought home our first professional championship in half a century. Goodyear still produces racing tires in Akron; so does Firestone, which announced that it plans to consolidate and expand its Firestone Firehawk race-tire operations on the south side in a state-of-the-art facility with a goal of rolling out more tires for the Indianapolis 500.

In a city filled with monuments to the captains of the rubber industry, Akron now plans to honor the everyday people who built their fortunes. A statue of a rubber worker holding a tire is scheduled to be unveiled this spring on a roundabout at South Main and Mill streets, in the heart of downtown Akron. Commemorative bricks with the names and positions of former employees will line a nearby plaza with an interactive kiosk telling the stories of the men and women who put America on wheels—workers like Perkins Pringle, Theresa Ciccarone, Robert Giles, and the Carson brothers.

These gestures of acknowledgement are important, and they mean something to former workers and their families. But they do not address or erase the effects of the industry on these workers’ life and health. We do not yet know, and we will perhaps never know, the extent to which people have been harmed by the rubber industry in Akron. But truly honoring workers will require dealing honestly and meaningfully with these toxic legacies—and ensuring that nothing like this happens ever again.

Yanick Rice Lamb, a native of Akron, Ohio, is a professor of journalism at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and co-founder of FierceforBlackWomen.com. Lamb was also a National Press Foundation Cancer Issues Fellow and a National Cancer Reporting Fellow through the National Institutes of Health and the Association of Health Care Journalists. She can be reached at ylamb@howard.edu.

Read more in Health

Worker Health and Safety

Inside the decades-long fight over an Ohio Superfund site

In Uniontown, Ohio, outside of Akron, residents and officials have clashed over cleanup of the Industrial Excess Landfill.

Worker Health and Safety

On a day to mourn workers who died on the job, COVID-19 looms large

As we mark Workers Memorial Day, a time to remember those killed or injured on the job, OSHA faces pressure to adopt coronavirus-related measures.

Join the conversation

Show Comments