Introduction

When the Food and Drug Administration unveiled graphic new health warnings for cigarette packs last week, an agency statement said the “bold measure” would “help prevent children from smoking [and] encourage adults who do to quit.” But the agency’s own research concluded that the impact of the warnings might actually be negligible.

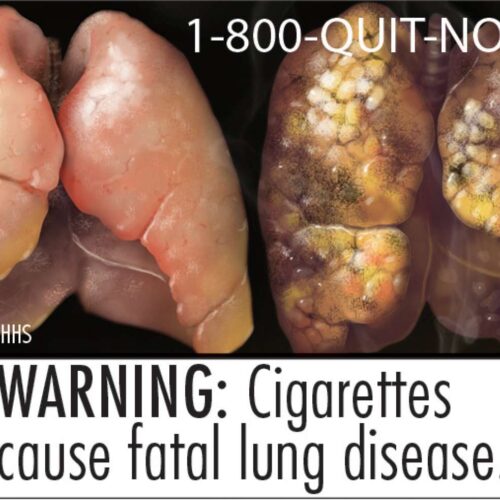

The required new warnings are an outgrowth of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009. When the label requirement is fully implemented in September 2012, all cigarettes made for U.S. sale or distribution will need to include one of nine graphic new warning labels on their packages. The FDA selected the nine from 36 images that were originally proposed, after reviewing scientific literature, considering 1,700 public comments and analyzing results from a survey of almost 19,000 people. Among the warnings are images of decaying teeth and lungs, children surrounded by smoke, and a photograph of a man wearing a shirt that reads, “I quit.”

But a close look at that survey’s conclusions casts doubt on the initiative’s potential for impact. “The graphic cigarette warning labels did not elicit strong responses in terms of intentions related to cessation or initiation [of smoking],” wrote the survey authors at RTI International, a North Carolina research institute, in their December 2010 report for the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products.

The FDA paid RTI $1.3 million to conduct the survey on reactions to the labels, which included a specific attempt to gauge the impact on African Americans, according to procurement orders iWatch News obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. The money did not come from taxpayer dollars, but from user fees cigarette companies are required to pay the federal government to regulate tobacco products.

The FDA collects user fees from the tobacco industry each year to pay for the Center for Tobacco Products. The budget totaled $235 million last year, a figure that — though substantial — is dwarfed by industry spending on marketing. A 2009 Federal Trade Commission report shows the industry spent $12.5 billion on marketing in 2006.

An FDA spokesman noted that the 2009 law required creation of the labels, and said the agency used portions of the survey that were helpful in making their determinations. “Whether to do or not to do the labels was not up for grabs,” FDA spokesman Jeffrey Ventura told iWatch News. “There was never a time that people were deciding whether or not to do this. It was, ‘what is the best way to do what is required under the law?’”

Despite the survey’s conclusions, the FDA estimates that the labels will “reduce the smoking population” by 213,000 within the first year. This widely reported number was cited in the FDA’s final rule published last week; the number was based on an FDA analysis of statistics from Canada, which began to require labels a decade ago.

According to Robert Cunningham, senior policy analyst at the Canadian Cancer Society, smoking rates have declined from 24 percent to 18 percent from 2000 to 2009. Canadian youths showed an even sharper decline in smoking from 25 percent to 13 percent over the same time span. Cunningham noted that other factors besides images on cigarette packs — such as tax increases and restrictions on smoking in certain places — likely played roles as well.

The FDA said it had accounted for “relevant differences” between the policies of the United States and its northern neighbor, enabling the agency to “isolate the effect of graphic warnings on smoking rates” and come up with the 213,000 figure. Cunningham said the estimate sounded reasonable, but others aren’t so sure.

Jeff Stier, senior fellow at the conservative National Center for Public Policy Research, said the labels are an example of what he calls “Why not?” policy-making: The requirements pose no opportunity cost for the government, monetary or otherwise, so they might as well do it even if the labels’ effects aren’t proven, he said. “They say it’s science-based, but the number is nothing more than speculation,” he said.

Dr. Gil Ross, medical director of the American Council on Science and Health, a New York-based consumer education group, also was skeptical, arguing that it was impossible to isolate the effects of the labels. “Their estimate is bogus and is designed to prop up their urge to impose these lurid, large warning labels,” he said.

“Exposure tends to have a diminished effect. The labels may cause a startle reaction but they tend to be taken in stride.”

In the FDA study, researchers inquired about participants’ emotional responses to the images, their recollection of them, their beliefs about the health risks of smoking — and their intentions to quit.

Though most of the study showed desired results — namely, that users had strong emotional reactions to the images, remembered them and understood the health risks of smoking — the survey did not show any intention to change smoking habits. Nor did it indicate that the images would discourage people from beginning to smoke.

Anti-tobacco groups, including the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, dismissed the survey’s conclusion about respondents’ intentions, however, arguing that the survey was meant to compare the reaction to each of the images as a way of weighing which would elicit the strongest emotional response.

Reaching conclusions about whether people might start smoking or quit smoking is virtually impossible from a survey involving such brief exposure to the labels, asserted Danny McGoldrick, the campaign’s vice president of research. “The exposure was so brief,” he said “If you see a Nike ad one time — are you going to go out and buy a pair of their shoes?”

McGoldrick predicted a big impact over time. “This is going to be a dramatic change in terms of what smokers encounter every time they grab a pack of cigarettes.”

The United States’ move toward graphic labels is representative of a larger international trend. Forty-three other nations have already passed legislation for putting labels on cigarette packs.

Canada led the way. “The international consensus is that picture warning works,” Cunningham told iWatch News. “A picture is worth a thousand words and can have more emotional impact. They are harder to ignore. That’s why companies use pictures in advertising — because they work.”

Information compiled by the Center for Tobacco-Free Kids showed that in Brazil, 54 percent of smokers had changed their opinions about the health consequences of smoking as a result of the labels, while 67 percent said the warnings made them want to quit. Surveys conducted in Singapore, Thailand, Australia and China showed similar outcomes.

Tobacco manufacturers oppose the new labels, arguing they are not realistic and are designed to elicit extreme reactions.

“The proposed graphic images include non-factual cartoon images, controversial photographs that appear to have been technologically enhanced to maximize an emotional response from viewers,” wrote Reynolds American Inc., one of the country’s leading producers of tobacco products, during a period for public comment on the FDA rules requiring the labels.

Reynolds American also challenged the FDA’s conclusions on the labels prospective impacts, alluding to the RTI survey showing little change in smokers’ intentions.

“In assessing the potential benefits of the proposed warnings, the rule relies on studies that not only are methodologically flawed, but also fail to demonstrate, even on their own terms, that the warnings will have any impact on smoking prevalence,” the firm wrote.

But the survey may simply have measured effects over too short a duration. A 2009 study published in the Journal of Consumer Affairs suggested that the images might take time to be effective tools.

Approximately 46.6 million Americans smoke, and one in five deaths are caused by smoking-related illnesses each year, according to 2008 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data. In addition, the CDC estimates the U.S. health cost at $193 billion annually.

To Cunningham of the Canada Cancer Society, opposition by the tobacco industry tells the whole story: its resistance suggests the labels have an effect. “If it didn’t work,” said Cunningham, “the industry wouldn’t oppose it.”

Ricardo Sandoval and the Center for Public Integrity’s International Consortium of Investigative Journalists also contributed to this story.

Read more in Health

Health

Doctors skittish about health technology despite promise of big federal bucks

Cleveland area physicians worried about big hassles, big risks and a big commitment of time they don’t have

Join the conversation

Show Comments