Introduction

As I was reading former Wall Street executive Greg Smith’s bombshell of an Op-Ed in the New York Times last week, I mentally inserted the names of the big for-profit health insurers — two of which I worked for — in place of Goldman Sachs, where Smith worked until resigning on the day his column was published.

Smith wrote that he decided to leave Goldman-Sachs because it had veered so far from the company he had joined straight out of college that he could no longer say in good conscience “that I identify with what it stands for.”

He put the blame squarely on Goldman’s current CEO and president. It was during their watch, he wrote, that “the firm changed the very way it thought about leadership.

“Leadership used to be about ideas, setting an example and doing the right thing. Today, if you make enough money for the firm (and are not currently an ax murderer) you will be promoted into a position of influence.”

Had Smith been an executive at any one of the big investor-owned insurers that have come to control the U.S. health care system, he could have written the same thing.

Like Smith, I came to realize toward the end of my career that the companies I had worked for had changed so much during my two decades with them that I could not in good conscience continue to serve as an industry cheerleader and spokesman.

Shortly before I turned in my notice in 2008, the human resources manager who had hired me nearly 15 years earlier turned in his as well. He told me that in his exit interview, his boss, the head of HR, told him — not with regret but with pride — that the company he was leaving was not the company he had joined. He was right, which is why that HR manager and I and many other former colleagues have left in recent years, dismayed at what the leaders of health insurance companies have come to value more than anything else: making big money for themselves and their companies’ shareholders.

Smith wrote in his op-ed that “not one single minute [at Goldman] is spent asking questions about how we can help clients. It’s purely about how we can make the most possible money off of them.”

In the many executive-level sessions I participated in over the years — including with peers from other companies at trade association meetings — I cannot recall one time in which we talked for a single minute about designing health benefit plans that truly were in the best interest of consumers. We talked instead about making sure policyholders had sufficient “skin in the game” to ensure “profitable growth.”

Smith soured on common practices at Goldman like persuading clients to invest in mortgage backed securities without mentioning to those clients that the company had already bet against those very same securities. By doing this, Goldman was guaranteeing itself a profit, even as some of its clients were losing a fortune and many of the rest of us were about to lose our homes and our jobs.

Similarly, I soured on common practices in the health insurance industry like refusing to sell coverage to children and others with “pre-existing conditions,” cancelling peoples’ coverage when they got sick and spending less and less every year of policyholders’ premiums on their medical care because of pressure from Wall Street analysts and investors.

As I wrote in Deadly Spin, “when your top priority is to ‘enhance shareholder value’ … you are motivated more by the obligation to meet Wall Street’s relentless profit expectations than by the obligations to meet the medical needs of your policyholders.”

What finally led me to begin questioning what I did for a living was the expectation that I would persuade people to believe things that I knew were not true — like the idea that shifting every American into what the industry euphemistically calls “consumer-driven health plans” would be in everyone’s best interest.

Marketing executive chose the term “consumer-driven” because it sounds better than what they really are: plans with high (and often extraordinarily high) deductibles. These plans are very profitable because people enrolled in them often have to spend thousands of dollars out of their own pockets for their medical care before their insurers will pay a dime. As a consequence, growing numbers of Americans — 30 million at last count, according to the Commonwealth Fund — are now finding themselves underinsured.

At a leadership retreat I attended a couple of years before I left my job, a vice president of a large insurer was trying to explain the benefits of consumer-driven care to a room full of colleagues who were hearing about the industry’s “consumerism strategy” for the first time.

During the Q&A, he was peppered with questions about how the plans could be a good deal for people with chronic conditions and people who didn’t have extra money to put in a savings account or otherwise meet high deductibles. After half an hour of nonstop questions, he finally said, “Look, you’re just going to have to drink the Kool-Aid.”

Sadly, most of them did. By doing so, like Smith’s fellow employees at Goldman Sachs, they had made a conscious decision to think more about their own compensation and their company’s bottom line than what is best for the rest of us.

Read more in Health

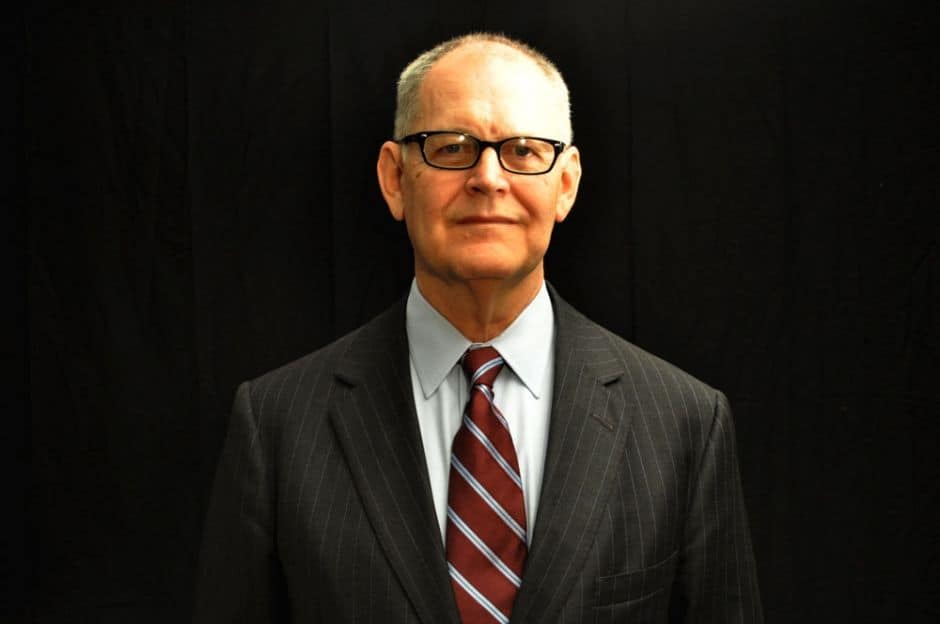

Wendell Potter commentary

ANALYSIS: Slogans versus substance in the battle over ObamaCare’s future

Cries of ‘Hands off my health care’ mask the benefits of the Affordable Care Act

Join the conversation

Show Comments