Introduction

Recent news releases from two very different organizations paint entirely separate pictures of what can happen to people once they sign up for a high-deductible health plan.

One release from Cigna, the giant for-profit insurance firm I used to work for, would lead us to believe that human resource managers who haven’t moved all of their company’s employees into a high-deductible plan should be canned for fiscal ineptness.

The other, from GiveForward, a Web site where people can create personal fundraising pages, tells of the real-world consequences when people in high-deductible plans become seriously ill or get hurt.

One of the reasons I left my job in the health insurance industry was because I could not in good conscience continue to promote high-deductible plans, often marketed as “consumer-driven” plans, as wise choices for most Americans. These plans, which are often coupled with a health savings account, have become a favorite of insurance company executives and an increasing number of employers. That’s because they enable insurers and employers to shift more and more of the cost of care from them to health plan enrollees.

Insurers regularly trot out studies, which they themselves conduct, as part of their ongoing campaign to persuade employers that haven’t yet joined in, to get with the program. Earlier this month, for example, my former employer released the results of the “Sixth Annual Cigna Choice Fund Experience Study.” A press release crowed that, “When American workers engage in health-smart habits offered in consumer-driven health plans, they reduced their health risks and lowered their total medical costs an average of $9,700 per employee over a five-year period.”

Cigna said it arrived at that figure from a review of claims submitted during that period by people enrolled in its consumer-driven health plans (CDHPs). And the good news just kept on coming. Not only were medical costs lower for people enrolled in CDHPs, but so were those folks’ health risks. That’s because, according to Cigna, they received higher levels of care, were “more engaged in health improvement” and were “more savvy” consumers of health care than people enrolled in more traditional health plans.

Maybe so, but studies of the population at large, and conducted by nonprofit organizations that don’t sell insurance — like the Commonwealth Fund — have found that high-deductible plans often are exactly the wrong kind of coverage for many Americans.

The Commonwealth Fund has found that adults in high deductible plans “have significantly greater difficulty” accessing care due to cost compared to people in plans with lower or no deductible, and that people who are very sick are at a particular disadvantage.

The Commonwealth Fund also discovered that folks enrolled in high-deductible plans are more likely to accumulate medical debt, especially those in low-income families.

These findings are borne out by the experience of the two young people who founded GiveForward in 2008, Ethan Austin and Desiree Vargas. In the four years since they launched it, GiveForward has helped families raise $10 million for out-of-pocket medical expenses.

I first learned about GiveForward while I was doing research for my column last month about Sarah Burke, the Canadian skier who died after an accident during a training session in Utah. Friends of the Burke’s family turned to GiveForward to help raise several hundred thousand dollars to pay for the care Burke received in the hospital before she died.

GiveForward marketing director Cate Conroy told me that Burke’s friends were among thousands of people who have turned to her organization for help to pay medical bills. Increasingly, the people seeking help have insurance they thought would be adequate but, because of the high deductibles or limited benefits, is anything but.

In fact, one of the first people to get help from GiveForward was Jessica Cowin, 28, who found out that her policy wouldn’t cover the cost of a kidney transplant her doctors said she needed. Her sister, Amy, put up a page on the Web site and, within a matter of hours, donations started pouring in. She says she probably would not be alive today if not for GiveForward and the hundreds of people who donated money.

As GiveForward’s Ethan Austin was quoted as saying in the news release, “There is a huge gap in this country between what insurance covers and what people are expected to pay when they get sick.”

The release also cited the results of a study last year by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which showed that 50 percent of Americans would have a hard time coping with a $2,000 expense, such as a medical copayment. Most high deductible plans have at least a $2,000 annual deductible. Some family plans now have deductibles as high as $50,000, although plans with such sky-high deductibles will be outlawed in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act. While the law will cap the amount of money Americans will have to spend out of their own pockets, it will not halt the trend toward “consumer-driven” care.

As more people are moved into these kinds of plans, GiveForward undoubtedly will become even more essential than it is today. Which speaks volumes about the state of the U.S. health care system.

Read more in Health

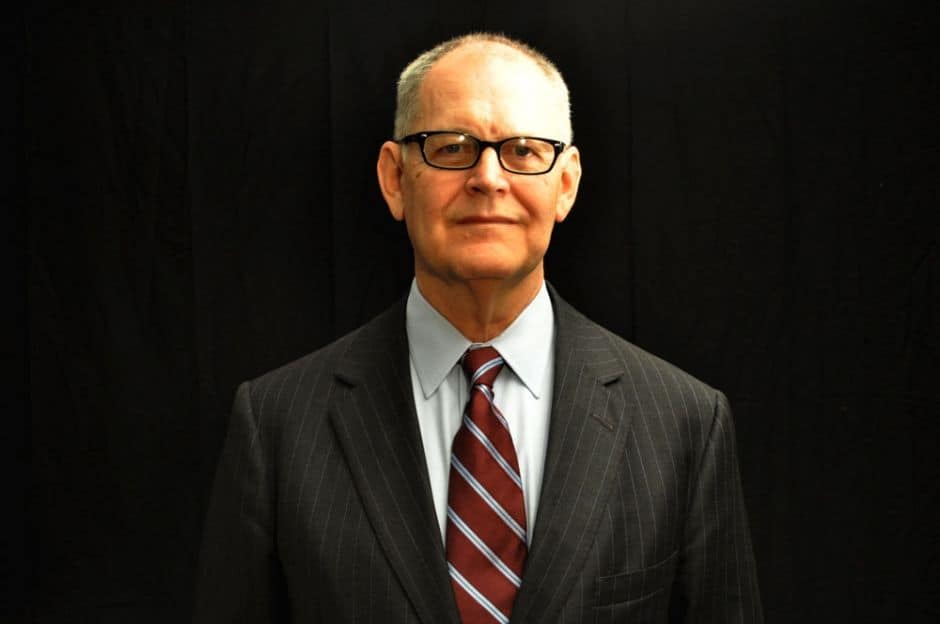

Wendell Potter commentary

ANALYSIS: The end of health insurance as we know it?

Speech by Aetna CEO signals a sea change in how Americans obtain coverage

Health

CORRECTED: States pushing efforts to require certification for cleaning medical instruments

Dangers of dirty surgical devices fuels new testing legislation

Join the conversation

Show Comments