Introduction

I wish every candidate for public office would be required to spend an hour or two volunteering at one of the free clinics operated throughout the country by a nonprofit organization, Remote Area Medical. The group bills itself as “pioneers of no-cost health care.” Its volunteer doctors and nurses travel to places where patients have been left behind, offering medical care to these forgotten ones.

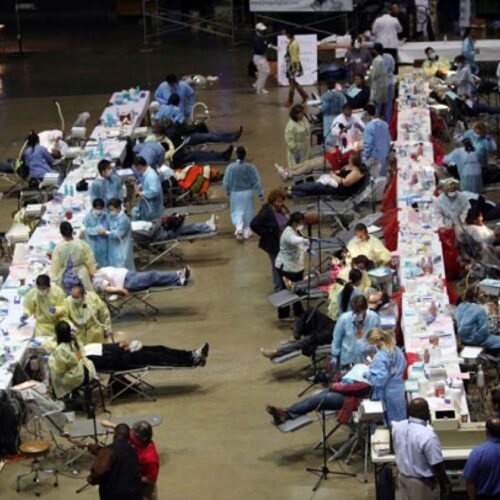

I visited one of their free clinics last weekend in Chicago. If the candidates witnessed what I saw, I’m betting they would finally understand just how much the U.S. health care system has deteriorated in recent years – and why, even now, health care reform must go forward.

If they had been with me at that Chicago clinic, I would have introduced them to 61-year-old Dariel Banks, who lost her health insurance last year when she was laid off. Since then, she has only been able to find part-time work and has not been able to find a health plan she can afford.

“I make just enough to cover my basic needs,” she told me, adding that she at times has had trouble making even that much money. “Once you fall behind, it just avalanches.”

Banks, who makes too much money to qualify for Medicaid and is not old enough for Medicare, was one of more than 2,000 people who came to RAM’s clinic at Malcolm X College, almost in the shadow of Rush University Medical Center’s gleaming new 14-story, $654 million tower that is scheduled to open in January. Malcolm X College is located in the midst of a vast complex of health care facilities, including Cook Country Hospital, now known as the John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital.

Although Cook County Hospital’s Web site says it’s services “are available to the more than five million residents of Cook County, regardless of their economic status or ability to pay,” it was clear from the long lines at the free Remote Area Medical clinic I was visiting that the medical, dental and vision needs of many people in the area are going unmet.

Simply put, the public hospital wasn’t reaching all of the public – even in urban, medical-rich Chicago, a place quite different from the medically neglected and isolated villages around the globe that Remote Area Medical’s founders had first envisioned serving a quarter-century ago.

At the organization’s Chicago clinic, many people come to see a dentist and to get new glasses, not just a medical checkup. It’s a good thing Banks did. The dentist she saw noticed a growth inside her mouth and recommended a biopsy. She’s hoping that if it’s cancerous, it was detected early enough.

Among the other people I met at the clinic were 14-year-old Joshua Wade, his sister Summer, and his grandmother, Deborah Carter. Joshua has been needing glasses for a long time, but his family couldn’t afford them. One of the most efficient operations at a free RAM clinic is its vision service. Within an hour or so of his eye exam, Joshua had his glasses, which he’s looking forward to wearing when he starts high school in a few weeks.

Most of the people who come to RAM’s free clinics are in households where at least one adult works – for an employer offering no health coverage.

A growing number, however, do have some insurance coverage. The problem is that their benefits are so limited or their deductibles are so high, they might as well be uninsured.

And those who have decent medical insurance often lack dental and vision coverage.

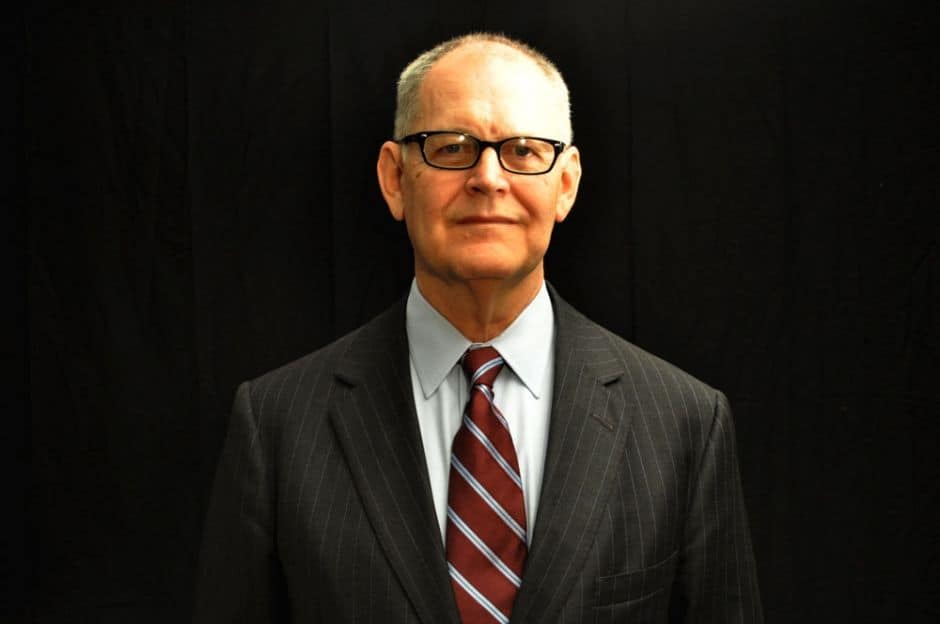

Stan Brock, who founded Remote Area Medical in 1985—initially to fly doctors in the U.S. to remote villages in South America and Africa—says the need for dental care is so great that RAM has a hard time finding enough dentists for the clinics. Of the many people who are turned away at some of the RAM clinics, most are there seeking dental care. (All the doctors, dentists, optometrists and other caregivers who treat patients at RAM clinics volunteer their time. Much of the equipment they use is also donated.)

RAM began holding clinics in the U.S. in the early 1990s. Although many of its expeditions are still to some of the world’s poorest and most remote places, most are now in this country. In fact, more than two-thirds of the thousands of patients treated at RAM clinics these days are Americans. Brock estimates that more than a half-million patients have come to RAM clinics seeking care since he started the organization.

To be sure, Brock steers clear of politics. He has friends on both sides of the political aisle in Washington and many state capitols. He refuses to talk about what he thinks of the health care reform legislation passed by Congress last year, or the efforts by many Republicans to repeal it.

At 75, however, nothing would make him happier than to be able to focus exclusively on the health care needs of the people he originally set out to serve—in places like Haiti and remote villages in South America.

But he doesn’t have time for wishful thinking. As soon as the last person was treated in Chicago, Brock and the few staff members who travel with him packed everything up and began the long drive west to the site of “RAM Expedition # 649” — also not to remote jungles but to another U.S. community in need, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. After spending four days there, the RAM crew will head to Kentucky, then to Virginia, and, finally, to Tennessee.

Clearly, Brock will have to stay busy until the nation’s leaders are ready to step up and fill in the growing life-and-death gaps in medical care.

Read more in Health

Health

Inkling of concern: Chemicals in tattoo inks face scrutiny

Tattoo ink can include some endocrine disruptors and toxic metals, as well as a compound that has been called one of the most potent skin carcinogens

Join the conversation

Show Comments