Introduction

What might the oil- and gas-rich Eagle Ford Shale region of South Texas look like in 2018?

A newly released but largely unnoticed study commissioned by the state of Texas makes some striking projections:

- The number of wells drilled in the 20,000-square-mile region could quadruple, from about 8,000 today to 32,000.

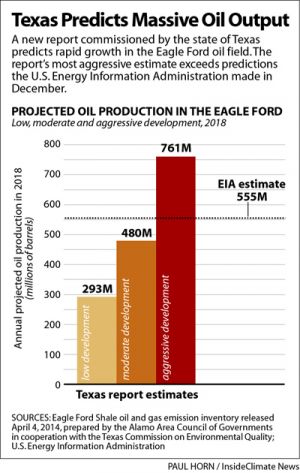

- Oil production could leap from 363 million barrels per year to as much as 761 million.

- Airborne releases of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) could increase 281 percent during the peak ozone season compared to 2012 emissions. VOCs, commonly found at oil and gas production sites, can cause respiratory and neurological problems. Some, like benzene, can cause cancer.

- Nitrogen oxides — which react with VOCs in sunlight to create ground-level ozone, the main component of smog — could increase 69 percent during the peak ozone season.

These projections are included in a study prepared by scientists with the Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG) in San Antonio and paid for by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). The study was designed to determine the extent to which oil and gas development in the Eagle Ford region is contributing to rising ozone levels in the San Antonio metropolitan area, which lies north of much of the drilling. San Antonio’s ozone readings have violated federal air quality standards since August 2012, making the city vulnerable to sanctions under the Clean Air Act.

The study’s findings also have implications beyond San Antonio.

In February, the Center for Public Integrity, InsideClimate News and The Weather Channel produced a series of reports about air quality in the Eagle Ford and found that the Texas regulatory system does more to protect the gas and oil industry than the public. The TCEQ has installed only five permanent air monitors in the region, which is nearly twice the size of Massachusetts, and all of them are on the fringes of the shale play, far from the heavy drilling areas where emissions are highest.

Peter Bella, AACOG’s natural resources director, said in a telephone interview that the San Antonio project has two components: a 260-page emission inventory that was posted without fanfare on the AACOG website April 4, and a photochemical model that uses numbers from the inventory and meteorological data to project how the Eagle Ford’s pollutants will influence ozone in San Antonio.

Findings from the photochemical model were given to the TCEQ more than two months ago and the agency is reviewing AACOG’s methodology. Bella said he did not know when the results would be released.

The TCEQ did not immediately respond to a request for comment Friday.

The emission inventory catalogs air pollutants from a range of oil and gas operations using three scenarios: low, moderate and aggressive development. (The numbers cited above assume aggressive development.) It was prepared with technical assistance from, and was reviewed by, the TCEQ.

State Rep. Lon Burnam, a Fort Worth Democrat, said the growth predictions are bad news for people who live in the Eagle Ford and surrounding cities, especially San Antonio. Burnam has tried unsuccessfully for years to pass legislation that would protect people from pollution associated with oil and gas production.

“The numbers are mind-boggling,” said Burnam, who recently lost a primary election for a 10th term. “Welcome to an increasingly dirty and unhealthy environment in a state wholly unsympathetic to the health and welfare of its people and wholly beholden to the industry.”

Omar Garcia, president of the South Texas Energy & Economic Roundtable, said Friday morning that he did not have the time to talk about the implications of the report. In previous interviews, Garcia has stressed the economics benefits of the Eagle Ford boom. His organization, which represents major operators in the region, says on its website that in 2012, the boom generated $61 billion in spending and more than 116,000 full-time jobs.

“I would love to engage,” Garcia told a reporter, explaining that he couldn’t spare even a few minutes. “We’ll get you on the next one.”

Drilling for decades to come

Documents obtained by the Center for Public Integrity and InsideClimate News under the Texas Public Information Act show that the AACOG study has generated intense scrutiny. In an email last May, for example, Bella told TCEQ scientists he had “recently been fielding questions on a weekly basis” about it from the media, local officials and academic researchers.

The results of the report, plus a separate inventory of non-Eagle Ford pollution sources, would help the fast-growing San Antonio metropolitan area prepare for future development, Bella wrote.

“We can’t afford to work through this critical juncture in San Antonio’s air quality history without comprehensive, accurate ozone data…including a comprehensive, accurate ozone precursor” emission inventory for the Eagle Ford, he wrote.

A final draft of the inventory was submitted to the TCEQ for review in December and released publicly a week ago, at the same time the agency was compelled to provide documents related to the report to the Center for Public Integrity and InsideClimate News under the Public Information Act.

The report relies heavily on industry publications and input from Eagle Ford operators with on-the-ground expertise. The document paints a picture of massive production growth over the next four years in a largely rural area already impacted by air pollution and other problems associated with five years of drilling.

Between 2008 and 2012, for example, 835 oil and gas wells were drilled in La Salle County — about one well for every nine residents. In neighboring McMullen County — population 730 — the ratio is one well per five residents.

Parts of the Eagle Ford could see active drilling through 2035, the report says, and wells could be more tightly packed. That could lead to more concentrated air emissions. Most of the growth is expected to occur in four counties — Webb, Dimmit, Karnes and La Salle. These counties were responsible for more than half of the Eagle Ford’s VOC and nitrogen oxide emissions in 2012.

Devine, Texas, lawyer Tomas Ramirez represents two Karnes County families in lawsuits against oil companies that claim emissions are sickening his clients. He called the AACOG projections “staggering.”

“It’s already dangerous if you live in close proximity to these sources of emissions,” Ramirez said. “So what does the future hold when you see such a huge increase? I think that the quality of life will substantially deteriorate for the people.”

Ramirez said he recognizes the vital role oil and gas plays in the Texas economy and that energy is a critical element in the overall stability of the country.

But the industry has to be more responsible, he said. Pollution controls “cost money and the oil companies don’t want to spend it. There is a way it can be done but the oil companies are not going to want to spend the money to do it.”

Extent of future emissions debated

Midstream operations — gas processing plants, compressor stations, storage tanks — will far surpass drilling rigs and well hydraulic engines as sources of ozone-forming pollutants, the AACOG scientists forecast. If the area develops as fast as some predict, midstream facilities could be producing 64 tons of VOCs and 49 tons of nitrogen oxides per ozone season day by 2018. That’s more than twice what was emitted in 2012. (In San Antonio, the ozone season runs from April through October).

Email exchanges between AACOG and TCEQ scientists show cordial discussions of the methods used to calculate pollution levels in the Eagle Ford. The emails also reveal the unique challenge of estimating emissions from a fast-developing industry where technologies are constantly evolving.

In an email on Feb. 24, 2014, for example, the TCEQ’s Michael Ege noted that AACOG’s numbers for emissions from pump engines were higher than estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, while AACOG’s emission calculations from oil and condensate tanks were lower than those used by the TCEQ.

The scientists met two days later to discuss the numbers, and AACOG’s Steven Smeltzer sent Ege an email on Feb. 27 to explain the discrepancies. Smeltzer said the EPA’s numbers were outdated, and that AACOG had used data from local industry sources and environmental consultants. AACOG also got its storage tank information from local operators.

Such disagreements aside, it’s clear the Eagle Ford is headed for explosive growth. The report notes that David Porter, a member of the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates drilling, said it will take nearly three decades to “fully develop” the Eagle Ford.

Tom Smith, director of the Texas chapter of Public Citizen, a nonprofit public-interest advocacy organization, said that kind of growth would exhaust the resources of the region’s counties and cities in terms of maintaining roads and providing services.

“The economic devastation to the communities will be extraordinary,” he said. “The demands for infrastructure will increase proportionally to the increase in activity. The tax base will struggle to pay the debt and clean up the mess made for decades.”

Amber Lyssy, who lives with her husband and three children on an organic farm in Wilson County, said their land is already surrounded by drilling rigs, flares, storage tanks and waste pits.

“Now, to think it’s going to get worse is scary,” she said

This story is part of a project by the Center for Public Integrity, InsideClimate News and The Weather Channel. Jim Morris is a senior reporter with the Center for Public Integrity. Lisa Song and David Hasemyer report for InsideClimate News.

Read more in Environment

Environment

Is this U.S. coal giant funding violent union intimidation in Colombia?

Alabama-based Drummond Co. sued for alleged ties to group behind deaths, threats

Join the conversation

Show Comments