Introduction

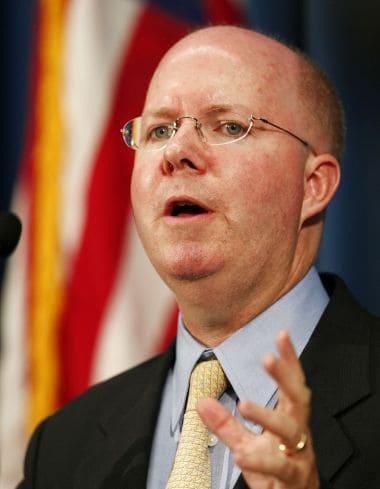

With Mitt Romney at or near the top of the polls in the race for the Republican presidential nomination, the Center for Public Integrity’s iWatch News wanted to find out how his administration might regulate toxic air pollutants. Although James L. Connaughton insists that he doesn’t speak on behalf of the campaign, he is a prominent supporter of the former Massachusetts governor and has been dubbed “the next EPA administrator” by some GOP insiders. Connaughton was chairman of the White House Council on Environmental Quality during both of George W. Bush’s terms. Since 2009, he has been an executive vice president at Constellation Energy. (The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

Q: How well have air toxics been regulated, in your view?

A: There’s been really good, strong regulation of industrial air toxics that were of high concern. The Toxics Release Inventory is wildly successful in creating an information-based incentive for companies to get out of air toxics. The two places where action on air toxics had been lagging is power plants and some of the toxics associated with petroleum fumes.

Q: Do you support a cap-and-trade regulatory system for air toxics?

A: The more market-based approach creates opportunities to optimize your pollution control of both [smog-forming compounds] and air toxics. Performance-based [regulations] set the target, usually based on benefit/cost, and then let the private sector sort out the most cost-effective way to get there. And there’s no better example of that than the acid rain trading program. Its main purpose was to deal with the acidification associated with power plant emissions. And no program has been more successful at lower costs, with lower bureaucracy, with virtually no litigation.

Q: How can you be sure that a cap-and-trade program won’t lead to pollution “hot spots” near poorer communities?

A: If you have a really effective and stringent market-based approach to air pollution, you’re going to get rid of a lot of your air toxics. Now, are you still left with peaks and valleys from one region to another? Yes. But are the peaks and valleys a lot smaller than they were before you did the market-based regulation? Absolutely. The “hot spot” becomes a less and less applicable concept as we get dramatic pollution reductions. You’re always going to have an unequal distribution of emissions of some sort, but pollution is so low now that, relatively speaking, the highs are just not that far away from the lows. Before, there used to be big differences.

Q: But what about people who live near industrial areas with heavier pollution?

A: That’s not an air pollution control issue; that’s a development issue. That’s a zoning issue. That’s not anything for a pollution regulator to deal with, other than to make sure that those facilities comply with applicable standards. As long as [a plant] is meeting the air quality standards, then it’s in compliance. Now, if you’re suggesting the air quality standards should be lower, there’s a process for doing that. But the whole point of the Clean Air Act is to set a reasonable ceiling on allowable pollution and let the communities sort out what kind of economic activity they want to meet air quality standards.

Q: In some communities the Center for Public Integrity and NPR visited for our Poisoned Places series, reporters found that enforcement has been uneven or absent. Is that finding consistent with your experience in the Bush administration?

A: That was an enormous frustration for me when I was doing policy. I think you’re right there, but it cuts in ways that are not popularly discussed. California holds itself out as being the most progressive when it comes to clean air control, but it remains the case that Southern California is still the area of the country most hopelessly out of compliance with air quality standards. What does it mean for California to have the strictest air quality standards when they have the worst air quality outcome? That’s the question that needs to be asked. Is it that you hide behind the more aggressive aspirational goal? If you think of the incredible steps that Texas has [taken] – or Ohio – to achieve federal air quality standards, how fair is it that Southern California [hasn’t]?

Q: Many facilities included on the EPA’s air pollution “watch list” are located in Texas and Ohio. Why do you praise their regulatory records?

A: In Texas or Ohio, they have a higher number of industrial facilities, where in Southern California they don’t and the pollution loads are much more diverse and people-centered, not industrial-centered. The fact is that [Texas and Ohio] have large emitters, but the states [are] making tradeoffs somewhere else. That’s the way the system is supposed to work. The feds set the standards, and the states say, ‘We’re going to achieve it these 200 different ways.’ So you can decide to have one mega-factory or a million transportation sources like California has. That’s a state choice as to how they’re going to allocate their [air pollution] load to stay in compliance with the standard.

Q: To what extent does the political influence of large industries affect Clean Air Act enforcement at the state level?

A: We are well past the point where that’s a real issue. The states are more locally accountable to their own constituencies and have very sophisticated institutions now and, quite frankly, some of the best experts I’ve encountered. And that runs from Ohio to Texas, to California to Maine, New York to Minnesota.

Q: What about facilities that continue to rack up violations?

A: All right, that’s something different. That’s just noncompliance. So those folks should be either penalized or shut down.

Q: How would you rate the Obama administration’s record on air pollution?

A: Their hands are kind of tied. They’re pressing ahead as they should. But it’s not optimal. At the end of the day, Congress has not taken a look at the Clean Air Act in 22 years. [Updating the law would diminish] the prospect of litigation on both sides. The biggest [barrier] to progress over the past few decades has been litigation and delay. Industry and environmental groups – both sides of the equation litigate, and [this leads] to delays. There’s no way to make up the cumulative emissions reductions that would have been avoided if we hadn’t suffered through all this litigation.

Read more in Environment

Environment

EPA hopes disclosure leads to greenhouse gas reductions

In release of new data, agency sees 25-year-old program as model to follow

Environment

EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory doesn’t offer full picture of pollution

Flawed database doesn’t capture all hazardous chemical releases

Join the conversation

Show Comments