Introduction

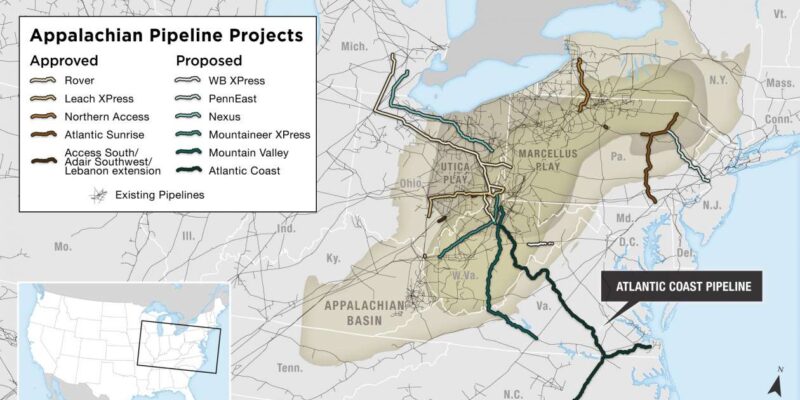

They landed, one after another, in 2015: plans for nearly a dozen interstate pipelines to move natural gas beneath rivers, mountains and people’s yards. Like spokes on a wheel, they’d spread from Appalachia to markets in every direction.

Together these new and expanded pipelines — comprising 2,500 miles of steel in all — would double the amount of gas that could flow out of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia. The cheap fuel will benefit consumers and manufacturers, the developers promise.

But some scientists warn that the rush to more fully tap the rich Marcellus and Utica shales is bad for a dangerously warming planet, extending the country’s fossil-fuel habit by half a century. Industry consultants say there isn’t even enough demand in the United States for all the gas that would come from this boost in production.

And yet, five of the 11 pipelines already have been approved. The rest await a decision from a federal regulator that almost never says no.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is charged with making sure new gas pipelines are in the public interest and have minimal impact. This is no small matter. Companies given certificates to build by FERC gain a powerful tool: eminent domain, enabling them to proceed whether affected landowners cooperate or not.

Only twice in the past 30 years has FERC rejected a pipeline out of hundreds proposed, according to an investigation by the Center for Public Integrity and StateImpact Pennsylvania, a public media partnership between WITF in Harrisburg and WHYY in Philadelphia. At best, FERC officials superficially probe projects’ ramifications for the changing climate, despite persistent calls by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for deeper analyses. FERC’s assessments of need are based largely on company filings. That’s not likely to change with a pro-infrastructure president who can now fill four open seats on the five-member commission.

“They don’t seem to pay any attention to opponents,” said Tom Hadwin, a retired utility manager from Staunton, Virginia. He doubts FERC will be swayed by the flood of written comments, including his own, and studies critiquing the Atlantic Coast pipeline. It’s the largest of the pending projects and would wind nearly 600 miles from West Virginia into his home state and North Carolina.

“FERC will issue the certificate,” Hadwin said. “They always have.”

FERC declined Center and StateImpact Pennsylvania requests to interview Cheryl A. LaFleur, its acting chairman, as well as senior officials. In response to written questions, the agency said it hasn’t kept track of the number of projects it denies. It provided a brief statement offering little insight into its pipeline-approval process. FERC spokeswoman Mary O’Driscoll wrote that, as a quasi-judicial body, “we must be very careful about what we say.”

In the statement, the agency said the Natural Gas Act of 1938 requires it to approve infrastructure projects that it finds would serve “the present or future public convenience and necessity.” FERC wouldn’t explain how it weighs competing interests; instead, it pointed to a 1999 policy outlining how it defers to market forces. That policy, still in effect, was influenced by, among others, Enron, the energy firm whose spectacular collapse in 2001 led to prosecutions and bankruptcy.

Former insiders defend the commission, describing its mandate as limited. Renewable-energy consultant Jon Wellinghoff, a FERC commissioner from 2006 to 2013, including nearly five years as its chairman, said the agency has little leeway for denying a pipeline. “It has to stay within the tracks,” he said.

Donald F. Santa Jr., a former FERC commissioner who heads the pipeline industry’s trade group, the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, said the agency’s low denial rate merely reflects the quality of the projects. They’re so expensive to build that few make it off the drawing board into FERC applications.

“It’s the envy of the world,” Santa said, referring to the nation’s pipeline network. “It is something that has enabled us to have remarkably competitive natural gas markets that have benefited consumers and the economy.”

Two former directors of the FERC office overseeing pipelines say no project survives the vetting process without route alterations or other changes. On occasion, FERC has delayed or rescinded approval of projects that don’t meet specific conditions. But at every turn, the agency’s process favors pipeline companies, according to Center and StateImpact Pennsylvania interviews with more than 100 people, reviews of FERC records and analyses of nearly 500 pipeline cases.

Among the findings:

● It’s hard to see where FERC ends and industry begins. Dozens of agency staff members have had to recuse themselves in recent years while negotiating jobs at energy firms. Most commissioners leave FERC to work for industry as well, in some cases lobbying their successors.

● Four of six major pending pipelines in the Appalachian basin were proposed by companies planning to sell pipeline capacity to utilities they own. Analysts who have scrutinized some of these cases say this new wave of self-dealing raises the risk of companies pursuing unneeded infrastructure that utility customers would end up paying for. FERC dismissed such concerns about two pipelines approved last year.

● The Obama-era EPA repeatedly asked FERC to scrutinize projects’ climate impacts, saying in a rebuke in October that its failure to properly do so did not comply with a key environmental law.

● FERC delays appeals of its pipeline approvals for months while allowing companies to begin construction. In seven cases since 2015, gas already was flowing in the pipeline by the time opponents could challenge it in court.

In February, on his last day as a commissioner, former FERC Chairman Norman Bay recommended that the agency evaluate the cumulative effects of increased gas production in the Marcellus and Utica shales, mostly in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio — an analysis environmentalists have advocated. Bay urged the agency to be more rigorous in its reviews.

“It is inefficient to build pipelines that may not be needed over the long term and that become stranded assets,” wrote Bay, an Obama appointee.

But FERC has resisted making such reforms. Now, with FERC down to a single commissioner and temporarily without a quorum, President Donald Trump gets to reshape the agency. Among those he has tapped for the commission is a pro-gas utility regulator from Pennsylvania, Robert Powelson, who in March likened protests against pipelines to “jihad,” later calling that “an inappropriate choice of words.”

“We’ve got abundant supply,” Powelson said at a gas-industry conference. “What we don’t have is adequate pipeline infrastructure.”

Close ties with industry

In the past few years, FERC has overseen what it says is one of the largest boosts in natural-gas pipeline capacity in American history. It issued certificates in 2015 for projects that collectively can carry 14.5 billion cubic feet of gas per day. The next year, it approved an additional 17.6 billion cubic feet.

Newly built pipe has helped move Appalachian gas to markets along the East Coast and in the Midwest, the agency says.

That, in essence, explains how FERC sees its role — dating to its birth in a decade marred by energy crises. In 1977, amid a natural-gas shortage and after an oil embargo by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, Congress created the agency and placed it within, yet independent of, the new U.S. Department of Energy. FERC’s mission: “Reliable, Efficient and Sustainable Energy.”

Proponents of the pipeline buildout argue that more American gas brings jobs to places sorely in need of them by fueling energy-hungry factories. And gas has bypassed higher-carbon coal as the dominant energy source in the U.S. But grassroots pushback is coming from both ends of the political spectrum, driven by concerns over the climate and individual property rights.

To such critics, FERC has come to epitomize a captured regulator.

Records obtained by the Center and StateImpact Pennsylvania through Freedom of Information Act requests reveal an exceptionally cozy relationship between regulator and regulated. Emails and official calendars from mid-2010 through 2016 show a steady march of industry representatives before commissioners. Large energy companies — Kinder Morgan, Dominion Energy, Energy Transfer Partners, Duke Energy — scheduled at least 93 meetings with FERC officials during those 6 ½ years. Trade groups like Edison Electric Institute and American Gas Association wooed commissioners and staff with invitations to executive dinners and after-hours parties. Former commissioners-turned-lobbyists, such as INGAA’s Santa, called on their successors.

By contrast, records show, FERC commissioners met with environmental and public-interest groups 17 times over this period.

In many ways, FERC operates like a one-way street: Commissioners may come to it from legislative or regulatory bodies, but almost always leave for industry. Eighty percent of the 35 former commissioners have spent at least part of their post-FERC careers at energy companies or law firms, trade groups and consultancies representing them. Many have ties to natural gas through work or positions on corporate boards.

There’s a similar pattern among FERC’s rank and file. Since 2012, staff members have submitted more than 50 requests to recuse themselves from regulatory work while seeking jobs at energy firms or consulting groups hired by the industry, agency documents show.

Some who have left FERC return to do the bidding of their new employers. In email exchanges in 2016, one woman who now works for Edison Electric Institute called on her former co-workers multiple times — seeking materials for an email blast, for instance, or inviting FERC commissioners to EEI events.

After FERC, jobs in the energy industry await

The lion’s share of FERC’s 35 former commissioners have spent some or all of their career after leaving the agency at energy companies or law firms and other organizations that assist them.

Source: Center for Public Integrity/StateImpact Pennsylvania analysis

“Are you ready for the protestors??” she wrote in one email to her former colleagues. “Too bad you guys can’t move the open mtg like last year. They just keep sucking!”

(Jie Jenny Zou/Center for Public Integrity)

Many critics see an inherent industry bias at FERC: Its budget is fully covered by fees collected from regulated companies. Last year, a Pennsylvania environmental group sued FERC over this funding mechanism, alleging it creates “a perverse incentive” for the agency to build pipelines. The lawsuit is on appeal after a federal court dismissed it in March, noting that Congress ultimately sets FERC’s budget.

This is the agency’s approval process: Take proposals as they come, see if the pipeline has long-term customer contracts, gather public feedback, try to keep local impacts to a minimum and assure basic safety standards.

J. Mark Robinson, an industry consultant, worked at FERC from 1978 to 2009, heading the office overseeing gas pipelines in his final years there. Interstate transmission lines often never go forward, he said, but FERC’s results speak for themselves. Pipelines get built; people get energy.

Pipeline companies, for their part, say the review process is exacting. Bruce McKay, senior energy policy director at Dominion, majority owner and operator of the Atlantic Coast pipeline, said the companies behind the proposal have submitted 100,000 pages of documentation to FERC and made 300 route adjustments to avoid ecologically sensitive areas at the agency’s request.

“They’re not there to do our bidding,” McKay said of FERC.

It doesn’t seem that way to Chad Oba, a mental-health counselor from Buckingham County, Virginia. There the Atlantic Coast developers plan to build a massive compressor station where engines would throb to keep gas moving. Oba attended a FERC meeting on the project in 2015, driving nearly an hour with as many neighbors as she could to testify. They didn’t want an industrial complex in their rural area, already crisscrossed by four gas pipelines. They questioned its siting amid a largely poor, African-American community founded by freed slaves.

“I thought, ‘Surely, these things will be considered,’” said Oba, of the anti-pipeline group Friends of Buckingham. But FERC has backed the location. The agency has never held a hearing in her county, despite requests from her group and a county commissioner.

“They’ve treated Buckingham very badly,” she said.

Such sentiments may not be what Charles B. Curtis, FERC’s first chairman, envisioned in 1979, when he wrote in congressional testimony that “we must create public confidence … and demonstrate that regulation can work effectively to promote the public interest.” At the time, he was looking to fund a congressionally mandated Office of Public Participation at FERC.

That never happened. Members of Congress couldn’t agree on funding for the office that year. The Center and StateImpact Pennsylvania found no evidence that FERC tried to launch the office again, despite congressional requests and a formal petition to do so.

Those seeking to challenge a pipeline frequently run into roadblocks. Before mounting a case in court, opponents must first appeal to FERC, which, by law, has 30 days to act. Yet records show commissioners routinely fulfill this obligation by granting themselves more time to issue a final ruling, leaving the challengers in limbo. Meanwhile, FERC allows pipeline companies to move ahead. By the time opponents get to court, construction can be well underway — or finished.

Ryan Talbott, an environmental lawyer at Appalachian Mountain Advocates, said he’s seen this pattern play out in every pipeline case he’s fought — more than a dozen so far. Last year, he set out to analyze FERC’s record on pipeline appeals. He found that commissioners take, on average, eight months to deliberate — then deny the appeals. A lawsuit filed against FERC seeks to have this practice declared unconstitutional.

The agency declined to comment.

FERC’s methods have fueled a grassroots campaign against it. Pipeline opponents have protested outside its Washington, D.C., headquarters since 2014. Some have gone on hunger strikes, interrupted commission meetings or picketed commissioners’ houses. Last year, 182 groups in 35 states called for congressional hearings into “the many ways communities are being harmed by FERC.”

Current and former officials consider the protests misplaced. Comprehensive energy regulation isn’t within FERC’s purview, they say; those who want changes should talk to Congress.

FERC opponents have done that, to no avail. But William Penniman, a retired lawyer who represented pipeline firms before FERC and is now active with the Sierra Club’s Virginia chapter, said the agency already has the authority to do more, yet chooses not to.

“Climate change, stranded assets, the construction bubble — they are not coming to grips with that,” he said.

Proposals to build, expand or modify interstate natural-gas pipelines in the shale-gas states of Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia soared in 2015. Companies sometimes split complex applications, such as the 11 most significant projects from that year, into more than one case before FERC.

Source: Center for Public Integrity/StateImpact Pennsylvania analysis of FERC data

Pressing FERC on climate

Gas-company executives often pitch their fuel to FERC as a long-term necessity for the country, filling in for renewable energy sources when the sun fades or the wind lags, powering industrial furnaces, heating homes. Companies propose new pipelines meant to last 50 years or more, presenting them as climate-friendly.

Environmentalists disagree, however, and are pushing FERC to dig deeper. Each additional gas pipeline, they warn, will make it easier to delay no-carbon alternatives and could lock in even worse effects of global warming.

Natural gas burns cleaner than coal, giving off about half the planet-heating carbon dioxide and a fraction of the toxic air emissions. Yet to avoid the worst of the heat waves, droughts, floods and other consequences of climate change, the Obama White House said the U.S. needed to cut greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 80 percent below 2005 levels no later than 2050. That’s all emissions from all sources, not just electricity and heating. And it’s 33 years from now, less than the lifetime of a pipeline.

Indeed, some advocates have calculated that new pipelines in the Appalachian basin would yield enough greenhouse-gas emissions from natural gas alone to surpass that goal.

That’s because the primary component of natural gas — methane — is a short-lived yet powerful greenhouse gas also contributing to climate change. Methane wafts into the atmosphere during every stage in the gas supply chain: Wells, processing facilities, pipelines and compressor stations all leak. Some vent methane by design.

The EPA has pegged the national rate at which methane escapes from oil and gas drilling sites at between 1 and 2 percent, based on industry estimates. Some independent research suggests that may be accurate.

But Robert Howarth, an environmental biology professor at Cornell University, estimates that methane emissions produced by shale gas from wellhead to delivery could add up to a 12-percent leak rate — causing substantially more warming in the short term than coal. Howarth sees the rapid rise in gas development as a contributor to the recent spike in global temperatures, including record-breaking heat waves in 2015 and 2016.

“The buildout of pipelines,” he said, “is a true climate disaster.”

Despite prodding from the EPA since 2013, FERC hasn’t taken a comprehensive look at the climate effects of gas projects before approving them. The agency only began estimating greenhouse-gas emissions from the burning of gas last year, and not in all cases. The total emissions for five pipelines, all pending: 170 million metric tons per year combined, the warming equivalent of 50 coal plants.

FERC refused to comment on its climate reviews, citing unspecified litigation. The Obama EPA contended that FERC has a duty to evaluate a pipeline proposal’s climate impacts under the National Environmental Policy Act. EPA officials said so in a pointed letter to FERC in October, after yet another pipeline review failed to estimate production or end-use emissions, calling the absence of these calculations “very concerning.”

The EPA says productive discussions have taken place since. But FERC has yet to evaluate greenhouse- gas emissions for pipelines as thoroughly as its counterpart urged.

It also doesn’t delve into whether electric utilities seeking gas for future plants could handle demand another way, such as energy efficiency and renewables. Such alternatives, FERC says in its reviews, would not fulfil the purpose of the project — “to transport natural gas.”

It boils down to a dispute about how far FERC can or should go.

“FERC has no legislative authority whatsoever to look at climate impacts,” said Wellinghoff, one of the only former commissioners with a renewable-energy background. “I would have loved to have had that authority at FERC, but I didn’t.”

Still, people keep pressing FERC to act. Last year, the Sierra Club and other groups sued the agency over its failure to calculate greenhouse-gas emissions from the since-built Sabal Trail pipeline, which runs from Alabama into Georgia and Florida. At a D.C. appellate court hearing in April, judges asked a FERC lawyer why the agency hadn’t done so.

The lawyer said FERC had determined the project wouldn’t meaningfully contribute to climate change. Judge Judith W. Rogers said it wasn’t possible to know that without doing the calculations.

“FERC said, ‘We’re just not going to do anything,’” she said.

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

Enron’s advice

In the 1990s, FERC posed this question: Was its pipeline-approval process working well? One company argued that the agency needed “to shift its focus away from command-and-control regulation towards policies that increasingly rely on market forces.”

That company was Enron. In 1999, its free-market views influenced FERC’s policy on how it would weigh projects. Years later, a New Jersey man fighting a pipeline that would run 167 feet from his daughter’s bedroom read the historical document with outrage and disbelief.

“You might have heard of Enron,” said Mike Spille, a software engineer trying to fend off the PennEast project, planned in Pennsylvania and his state. “It was a big giant bubble company that exploded and lots of people went to jail. Companies like Enron are the ones that set this FERC policy, and it’s part of the reason why it’s so bad.”

For the agency, customer contracts for pipelines are “strong evidence” of what the market wants. Since 1999, it has never denied a project that had them. The two it rejected did not.

Pipeline company executives believe this makes sense. No developer would sink potentially billions of dollars into an unnecessary project, they say. No utility or other gas shipper would pay millions of dollars for unneeded capacity.

But relying on contracts to judge need can be problematic. The Appalachian pipelines illustrate that.

First off, some of them are getting eminent-domain authority to take gas out of the country — there simply isn’t enough domestic demand, analysts say, which is something FERC does not consider.

Three new or pending Appalachian pipelines have space set aside for gas going to Canada. Another played up its proximity to Dominion’s nearly complete export terminal in Maryland. Even projects pitched as purely domestic might not end up that way — pipelines interconnect.

Beyond that, many of these pipeline contracts have an incestuous quality. Companies are building them for their own subsidiaries — mostly electric or gas utilities and gas producers. It’s as if one hand wrote the contract and the other signed it.

Industry experts say this trend increases the risk of overbuilding. One reason is that interstate pipelines are more profitable than power plants and other infrastructure that utilities erect for themselves.

“It’s a nice way to make money,” said Greg Lander of Skipping Stone, a gas- and electric-industry consulting firm. “The market need isn’t there.”

Lander’s firm, hired by an environmental group to examine PennEast, found no economic justification for the pipeline, which will mostly serve utilities and other firms owned by the developers. The New Jersey agency representing utility customers is also skeptical.

“NJ Rate Counsel is concerned that … the ‘need’ for the Project appears to be driven more by the search for higher returns on investment than any actual deficiency in gas supply,” the agency wrote to FERC last year.

It urged FERC to examine whether the contracts reflected true demand. FERC didn’t. Instead, it gave the pipeline a preliminary thumbs-up, the last step before approval.

PennEast spokeswoman Patricia Kornick said the project would improve reliability and ease price fluctuations. Companies signed up “because they recognize the need for an abundant, reliable, clean energy source,” she wrote in an email.

Het Shah, who leads natural gas market research at Bloomberg New Energy Finance, a consulting firm, said the Appalachian boom isn’t just about new pipelines, but also older ones turning flow around to push gas out of the region. It’s “definitely an overbuild,” he said, but he sees a strategy driving it — exports.

U.S. gas moved by pipeline to Canada and Mexico tripled in the past decade, with more coming. There’s also a rush to build liquefied natural gas terminals to ship product overseas.

International markets could help Appalachian producers battered by low prices. But it makes landowners along pipeline routes livid. They don’t see how it’s in the public “convenience and necessity” to seize private property in America so firms can make money selling gas outside the country.

(Rover owner Energy Transfer Partners, via the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency)

That’s what people told FERC about Northern Access 2016, a Pennsylvania-to-New York pipeline that would feed much of its gas to Canadian markets. The commissioners said in February that this was a matter for the Energy Department — not noting that the other agency automatically approves exports to Canada.

The point, FERC said, was that all the capacity had been contracted. It approved the pipeline.

The fight on the ground

The policy debates around pipelines can seem far away to those living in isolated communities in west-central Virginia, the epicenter of opposition to the Atlantic Coast project. Residents who don’t consider themselves environmentalists don “NO PIPELINE” T-shirts and hats and routinely show up at opposition rallies.

In Virginia, as in many places on proposed construction routes, the threat of eminent domain fuels this fight. Landowners say they object to the idea that companies can take private property — seizing permanent pathways, 75 feet wide or more — for corporate gain. They say the one-time payments they’re offered don’t make up for what they’re losing.

These landowners include Becci Harmon, a drug-and-alcohol program officer from Swoope, whose house sits within 50 feet of the Atlantic Coast route; she fears the one-acre plot on which she’s lived for 26 years will turn into a gutter after the pipeline wipes out her trees, garden and septic system. Richard Averitt, an entrepreneur from Nellysford, believes it will jeopardize his plan to develop an “eco-friendly” resort after it cuts the wooded, 100-acre site in half.

“This pipeline in particular is so egregious. It’s 95 percent virgin land,” Averitt said. “It’s land privately owned or in the public trust.”

Atlantic Coast became an issue in Virginia’s recent gubernatorial primary, but Dominion and Duke say supporters outnumber opponents. The companies point to recent polling by an energy industry group that includes Dominion among its members. Its survey shows that 55 percent of residents back the project while 30 percent oppose it. They also cite a letter, signed by 16 state lawmakers from Virginia, North Carolina and West Virginia, urging FERC officials to approve the pipeline. Last month, a New York watchdog group released a report revealing that five of the signatories are top recipients of either Dominion’s or Duke’s political contributions.

Supporters writing op-eds distributed by the companies include landowner Ward Burton. He was impressed that Dominion altered the project’s route to avoid crossing a creek twice and a forest once on the 565 acres in Blackstone, Virginia, owned by his wildlife foundation.

Unions are eager to see the pipeline move ahead. “We’re going to put people to work,” said Matthew Yonka, president of the Virginia State Building & Construction Trades Council.

Still, there can be localized problems. The Rover pipeline, which runs from Pennsylvania to Michigan, racked up more than $900,000 in proposed penalties from Ohio regulators after FERC approved it in February. Officials say its owner, Energy Transfer Partners, kept spilling drilling fluid into wetlands, ponds and streams — including, in one case, several million gallons of a clay mixture tinged with petroleum.

Energy Transfer’s Alexis Daniel said the company considers land restoration “a top priority” and is working to resolve the matter. Craig W. Butler, who heads the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, said the company claimed the state has no authority to penalize it. He’s grateful FERC intervened: It’s halted certain drilling work on the pipeline while investigating the damage.

Some states, less impressed with FERC’s process, have pushed back. New York regulators denied necessary water permits for two pipelines, the Constitution last year and Northern Access in April. Both projects are on hold as the developers wait for a federal appeals court to decide whether the denials can stand. In its most recent permit rejection, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation said “FERC disregarded the Department’s concerns.” Based on its experiences with gas pipeline construction, the state agency predicted “significant degradation of water quality in stream after stream.”

U.S. Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman, a Democrat from New Jersey, wants to see reforms earlier in the process — when FERC is still deliberating. Pressed by residents upset about PennEast, she sponsored legislation in May that would require evidentiary hearings in contested cases and regular, big-picture reviews of need.

Absent a state veto or major changes at FERC, there’s little a landowner can do to stop the construction juggernaut, as Jeb Bell learned. He and his brother didn’t want the Sabal Trail pipeline burrowing beneath their tree farm in Mitchell County, Georgia, so the company took them to court twice — first to get permission to survey the land and then to build on it. Sabal Trail, largely owned by Enbridge, won each time. It also fought off the Bells’ counterclaim contending the company had trespassed on their land.

Then the company won the right to collect legal fees from the Bells — $47,258 in all.

Enbridge spokeswoman Andrea Grover said by email that Sabal Trail is entitled to the money because it had offered to settle the “baseless” trespass claim; the brothers turned it down.

Bell, a state-park manager, has no idea how he’ll pay if his appeal fails. He can’t imagine a multibillion-dollar company needing his money. What it wanted, he’s sure, was to send a warning to other landowners: Don’t even try to stop pipelines. They always win.

Marie Cusick of StateImpact Pennsylvania contributed to this story.

Join the conversation

Show Comments