This story was reported as part of a partnership between E&E News and the Center for Public Integrity. It was co-published by the Houston Chronicle.

Introduction

In just three years, a 1,000-acre complex surrounded by Louisiana swampland has become the unlikely epicenter of America’s booming natural gas business.

Sabine Pass terminal is the crown jewel of Cheniere Energy, a Houston company that had a virtual monopoly on U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas, or LNG, until last spring. In November, Cheniere opened a second terminal — eclipsing competitors racing to construct their first sites. The company is in talks to close its third deal with China, worth an estimated $18 billion.

But cracks in Cheniere’s runaway success story have started to show.

Last year gashes up to six feet long opened up in a massive steel storage tank at Sabine Pass, releasing super-chilled LNG that quickly vaporized into a cloud of flammable gas. Federal regulators worried the tank might give way, spilling the remainder of the fuel and setting off an uncontrollable fire. It wasn’t an isolated event: Another tank was leaking gas in 14 different places. Both tanks remain out of service over a year later.

Investigators soon discovered that Cheniere grappled with problems affecting at least four of the five tanks at the terminal over the past decade. And officials at the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, known as PHMSA, have found the company to be less than forthcoming in the ongoing investigation, noting Cheniere’s “reticence to share [its] sense of what might have gone wrong.”

The leaks are a red flag at a time of unprecedented expansion in the LNG industry, which promotes the fuel as not only safe but also a clean, more climate-friendly alternative to coal. The problem is that natural gas is made up mostly of methane, a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the Earth’s atmosphere. Leaks erode the fuel’s climate advantage over coal.

Cheniere spokesman Eben Burnham-Snyder said workers and the public were never in danger, and last year’s leaks were about one hundredth of a percent of the facility’s permitted greenhouse gas emissions for the year. The tanks, he added, meet “all federal and state safety requirements.” But some other LNG export projects — including Cheniere’s newest terminal in Corpus Christi, Texas — have opted to use more expensive tank designs that offer greater protection against leaks and fires.

Sabine Pass was originally designed for imports. In 2012 Cheniere began converting the facility to handle exports instead, taking advantage of surging gas supplies from the shale drilling boom. The company upended the energy market when it began sending LNG overseas in 2016, quickly turning America into a top seller of the fossil fuel.

Over a dozen U.S. export projects are now in development, including a $10 billion project by ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum on the Texas side of Sabine Pass. Federal regulations, though, haven’t kept pace. They were written for simpler import and gas-storage facilities, not complex, multibillion-dollar export facilities. In April, the White House directed regulators to update LNG safety rules. But it’s unclear what that will look like — or whether any new design requirements would apply to projects already in the works.

The industry trade group Center for Liquefied Natural Gas said its members — which include Cheniere — support the effort to revamp current regulations. That “goes hand in hand with our industry’s focus on continuous improvement,” spokeswoman Daphne Magnuson wrote in a statement. “We see a bright future for U.S. LNG and significant benefits to the planet at large.”

‘A continuing public safety threat’

On January 22, 2018, a Sabine Pass worker saw a pool of LNG vaporizing in the night air beside one of the storage tanks. Paint had peeled off the side and ice had formed at the top. The company mobilized, securing the area.

The biggest immediate risk was that the cloud of low-lying natural gas building around the tank could have drifted until it hit an ignition source — static electricity, for instance — and burst into flames. Two days later, Julie Halliday, a senior accident investigator with PHMSA, inspected the tank and found the outer wall had cracked in four places and was still leaking gas.

Investigators also found vapor escaping from more than a dozen points around the base of a second tank, suggesting damage there, too. On February 8, PHMSA ordered both tanks shut down. During a public hearing in Houston in March, Halliday said there would be no way to put out an entire tankful of LNG if it caught fire.

“Sabine has been unable to correct the long-standing safety concerns … and cannot identify the circumstances that allowed the LNG to escape containment in the first place,” PHMSA wrote in its uncharacteristically forceful order. “Continued operation of the affected tanks without corrective measures is or would be hazardous to life, property and the environment.”

Cheniere quickly went into damage control mode, fighting the order while playing down the risks to the roughly 500 people who work on-site. “We want to stress that there was and is no immediate danger to our community, workforce, or our facility from this incident, nor is there any impact on LNG production,” Burnham-Snyder, the spokesman, said at the time.

Cheniere has been tight-lipped even with investigators. But information has trickled out, suggesting deeper problems at the site. During the investigation, the company acknowledged that four of its five tanks had experienced a total of 28 temperature anomalies since 2009, increasing in frequency after the shift to exports in early 2016. Cold spots on LNG tanks can suggest leaks or insulation problems, and when the outer wall of a tank like those at Sabine Pass gets too cold, it can become brittle and crack.

In the summer of 2016 the company hired consultants to study the temperature problems but didn’t inform regulators or share the report with them until after the 2018 leaks. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, requires LNG companies to disclose temperature deviations. Cheniere’s filings for that period read: “None to report.”

Asked about the discrepancy, the company’s spokesman did not address it but wrote, “Cheniere is committed to compliance and timely reporting.”

PHMSA’s investigation is ongoing; it has not fined Cheniere for the 2018 incident or its reporting failures. The agency has not provided the public with basic records about the leaks, citing an ongoing review of the company’s confidentiality concerns. Cheniere, in fact, threatened to sue PHMSA if it released additional information in response to public records requests.

A lawyer for the company sent a seven-page letter to the agency in August, warning that disclosure would cause “irreparable commercial and competitive harm to Cheniere” by revealing its facility design. “Competition amongst LNG export projects to complete construction in the most efficient manner possible and to provide lowest prices to customers is vital to continued success,” the letter added. In October, a Cheniere attorney agreed to PHMSA’s request for an informal meeting to hash out how best to address the leaks, but only if the agency affirmed it would keep the company’s records confidential.

But even PHMSA’s patience has limits. In February of this year, the agency rejected Cheniere’s repair plan for one of the tanks, calling the proposal inadequate and saying it would amount to “a continuing public safety threat over the years and decades to come.” Burnham-Snyder said the company has since reached an agreement with the agency and is moving forward with repairs. It expects to have the tanks in service by the end of this year.

Ernie Megginson, an engineer who consulted on another project, Magnolia LNG, said he doesn’t understand Cheniere’s secrecy about the incident.

“There’s no reason a specific tank design or a drawing or a photo of the incident cannot be shared publicly,” he said. “For an issue of this magnitude, Cheniere, as a leader in this industry, should lead the way in safety and transparent reporting.”

Regulatory vacuum

The problems at Sabine Pass may not extend broadly across the industry for the simple reason that a number of new projects are opting to use safer tanks.

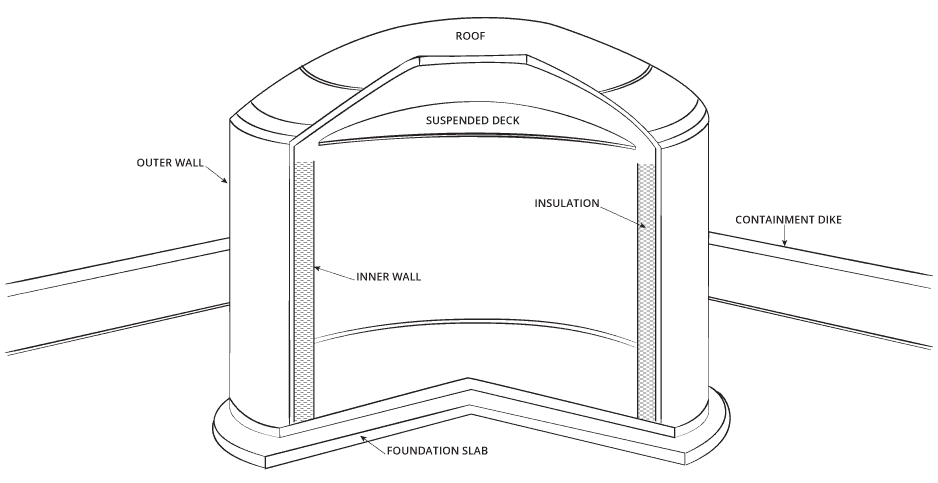

The ones at Sabine Pass have a single layer of steel that can withstand LNG’s ultra-cold temperatures. That inner wall is surrounded by a second layer of steel that holds insulation in place but isn’t meant to come into contact with the LNG, and placed in a pit large enough to capture the entire tank contents in case of a spill. Several export projects that started out as import terminals use that tank design. But all brand-new, approved projects will use a more expensive design with two layers of cold-tolerant material instead of one, allowing the tank’s outer wall to serve as a second layer of containment in case of an LNG spill.

The cheaper design is allowed under federal regulations. But Megginson said he was warned early on that it would be difficult — maybe impossible — for Magnolia LNG to get that option approved.

“FERC can be persuasive,” he said, noting that the agency could impose additional rounds of engineering review that would add up to a costly delay.

Texas LNG, Venture Global LNG and Cheniere’s own Corpus Christi plant are among the projects that originally proposed using the cheaper tanks but changed course. When it updated its design, Texas LNG cited a lower fire risk associated with the pricier option.

Keeping the original tanks at Sabine Pass saved Cheniere time and money. A 2018 report by The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies shows construction costs there were a little more than half that of Corpus Christi, thanks to Sabine Pass’ existing tanks and jetties for imports. The same paper said the more expensive design is “intrinsically safer” and has become the industry norm.

Asked why it used different types of tanks at its two sites, Cheniere wrote in a statement that it considered “the particular location, needs, and characteristics of each facility, and has demonstrated that both tank design options can safely meet our business and operational requirements.”

FERC spokeswoman Tamara Young-Allen said the agency “does not have a preference on the type of tank” and either could be suitable, depending on the size of the site. The cheaper tanks “usually require a significant amount of land in order to meet the PHMSA’s regulations,” she said.

Tank design isn’t the only area where federal rules haven’t kept up with the LNG industry. In 2016, research commissioned by PHMSA suggested explosions are a bigger risk at export facilities than import terminals because of flammable gases used to liquefy natural gas. FERC instructs companies to calculate the consequences of a potential explosion at their facilities, but LNG safety expert Jerry Havens warns that these assessments may severely underestimate the risk.

Havens described the worst-case scenario as “cascading explosions that could destroy a plant and possibly extend damages to the public beyond the facility boundary.”

‘Operational excellence’

Cheniere has been key to the Trump administration’s “energy dominance” agenda, which centers on oil and gas exports. In November, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross helped Cheniere unveil its Corpus Christi terminal, the country’s first LNG export facility to be built from scratch. That same month, Energy Secretary Rick Perry appeared alongside company executives in Poland to celebrate a 20-year contract. Billionaire investor Carl Icahn, a longtime Trump confidant who served briefly as a special White House advisor, is Cheniere’s largest shareholder as of March.

The company’s early start has all but guaranteed success. It reported $471 million in profit for 2018 and is projected to become one of the world’s top five suppliers of LNG next year — the same time a handful of competitors are expected to bring their first terminals online.

But the company was on the verge of collapse when it took a multibillion-dollar gamble to retrofit Sabine Pass for exports. In his book The Frackers, Wall Street Journal reporter Gregory Zuckerman details a 2009 meeting in which the co-founder of natural gas producer Chesapeake Energy convinced skeptical Cheniere executives to make that pivot. Chesapeake would be able to sell more natural gas and Cheniere, “a company that seemed on its last breath,” would avoid financial ruin, Zuckerman writes. Cheniere enlisted Washington power brokers to make the case for LNG exports.

By the end of President Barack Obama’s first term, natural gas had become a fixture of his energy strategy. In early 2012, he spoke glowingly of natural gas as an economic and environmental plus, predicting the country would soon be exporting it. Two months later, federal officials approved Cheniere’s export plans.

“I would credit most of the company’s success not to the implementation of a long, hard, thoughtful vision, but sort of serendipity and good luck,” said Tyson Slocum, energy director at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy organization. “Cheniere is the concession stand at the movie theater of the U.S. fossil fuel business.”

It’s no wonder, said Slocum, that Cheniere is stocked with ex-Obama officials. Among the company’s ranks are former Energy Department officials Burnham-Snyder (now company spokesman), Christopher Smith (now a senior vice president), Robert Fee (now chief of staff) and Steven Davidson (now community affairs manager).

From 2014 until last year, Obama climate “czar” Heather Zichal sat on Cheniere’s board of directors — earning more than $1 million in compensation, including company stock. Zichal, who now oversees corporate engagement at The Nature Conservancy, declined to comment about her role on the board but said she has divested her Cheniere shares. While at the White House, Zichal was an early architect of the Clean Power Plan, a climate policy that would have pushed states away from coal toward natural gas and renewables but was withdrawn by President Donald Trump.

Cheniere has positioned itself as a leader on climate and sustainability. On its website, the company acknowledges “the scientific consensus on climate change,” calls the Paris climate accord a “good start,” and champions efforts to capture carbon emissions. Its website reads, “Cheniere sees natural gas as a fundamental energy source in the energy transition to a lower carbon future, along with renewable sources of energy.”

But increasingly, environmentalists do not. Ongoing research has produced mounting evidence suggesting natural gas isn’t much better than coal for the climate because of widespread methane leaks. That research does not yet account for LNG exports, which likely worsen the total climate impact for gas.

Industry’s response has been somewhat contradictory. In 2018, Cheniere joined oil and gas titans like ExxonMobil and Chevron to form a research group aimed at reducing methane emissions. But those same companies, including Cheniere, also belong to the American Petroleum Institute, a trade group that has aggressively lobbied against methane regulations it called “overly burdensome” and “costly.”

That stance runs counter to Cheniere’s oft-repeated motto of “operational excellence.” The company website notes that “LNG has positive climate benefits, but excessive methane leakage can erode this advantage.”

That’s not the only threat methane poses to the company. Cheniere has cited worsening disasters from climate change as a business risk, including 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, which temporarily shuttered Sabine Pass.

“Changes in the global climate may have significant physical effects, such as increased frequency and severity of storms, floods and rising sea levels,” the company’s 2018 annual report warned. “If any such effects were to occur, they could have an adverse effect on our coastal operations.”

Jenny Mandel is a reporter at E&E News, an outlet covering energy and the environment. Jie Jenny Zou is a reporter at the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative newsroom in Washington, D.C.

Join the conversation

Show Comments