Introduction

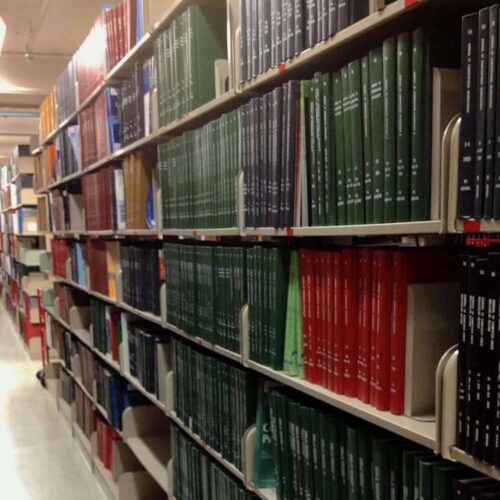

Hardbound volumes of Critical Reviews in Toxicology and Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology spanning decades are shelved at the National Library of Medicine’s subterranean archives — the world’s largest medical collection — in Bethesda, Maryland.

The peer-reviewed journals are among a select group of medical titles indexed by the National Institutes of Health, and they belong to international associations whose members pledge to uphold ethical and scientific standards. The titles come at a price: an issue of Critical Reviews retails for $372, while an annual subscription to Regulatory Toxicology costs $275.

Yet critics also claim the journals are purveyors of “junk science” — misleading, industry-backed articles that threaten public health by playing down the dangers of well-known toxic substances such as lead and asbestos. The articles often are used to stall regulatory efforts and defend court cases.

An analysis by the Center for Public Integrity found that half of all review articles written by top scientists at the consulting firm Gradient since 1992 were published either in Critical Reviews or Regulatory Toxicology. No other journal came close.

“You’d have to be delusional to not recognize that the issues they’re dealing [with] and policies they’re setting won’t affect the profits of very powerful sources,” said Canadian anti-asbestos activist Kathleen Ruff, who called both journals “egregious examples” of a deeper problem of industry influence. “Creating doubt is an endless activity and, in the meantime, people die unnecessarily.”

Editorial boards at both journals are laden with scientists and lawyers employed by industry, making them easy targets for public-health advocates. Current board members include private consultants who have also received compensation as expert witnesses in court.

“The harm is that it actually muddies the independent scientific literature,” said Jennifer Sass, a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an environmental group. “They’re stacking their weight on their side of the scale.”

Those behind the journals deny that industry relationships compromise scientific independence.

“There is this prevailing issue, which is really unfortunate, that anything supported by industry is tainted,” said David Warheit, a Critical Reviews board member and scientist at Chemours, which manufactures titanium dioxide, an ingredient in sunscreen. “Perceptions pervade everything.”

Warheit said each submission to the journal is evaluated by four or five peer reviewers as opposed to the typical two or three. “I have reviewed some awful papers for [Critical Reviews in Toxicology], and they didn’t get published.”

New Mexico veterinarian and Critical Reviews editor Roger McClellan declined an interview request from the Center, writing in an email that he was proud of the journal’s 45-year history. “My scientific record speaks for itself,” he added, providing copies of his 64-page résumé and biography.

Gio Gori, editor of Regulatory Toxicology, also declined to comment and referred all questions to the publisher, Elsevier. A spokesperson cited a 2003 editorial by Gori, which referenced the journal’s objectivity and “more than 600 international scientists who generously assist in the journal’s peer-review process.”

Chaos and turmoil

Epidemiologist Philippe Grandjean was one of 42 scientists who signed a letter in late 2002 criticizing Regulatory Toxicology’s frequent failure to disclose conflicts of interest and deep industry ties, starting with Gori.

A former director of the National Cancer Institute, Gori made millions as a tobacco consultant questioning the dangers of secondhand smoke in scientific journals as well as The Washington Post.

“Gori is the kind of guy who would write especially obnoxious editorials where he would castigate honest scientists as being out of their minds,” said Grandjean, a Danish epidemiologist. “It was so blatantly biased towards industry and against open and transparent science.”

Elsevier stood by the journal but implemented a disclosure policy in 2003.

A decade later, Grandjean found himself drafting another letter — this time airing his concerns about Critical Reviews, where he served as a board member.

An adjunct professor at Harvard School of Public Health and a pioneering mercury researcher, Grandjean said he joined the Critical Reviews board more than 30 years ago despite its reputation for being cozy with industry because he believes in collaboration and felt he could have a say in the journal’s content.

That changed in 2012 when the journal published two articles rebutting research from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health linking lung cancer to diesel fumes. Grandjean said the publication “wasn’t science for science’s sake,” but a way to cast doubt on NIOSH’s findings.

His complaints got no traction with editor McClellan or then-publisher Informa Health, which Grandjean said reneged on promises to conduct an independent review. Taylor & Francis, the current publisher, declined to comment. In 2012, McClellan defended the journal’s disclosure policies and said that Grandjean’s complaint had been shared with other members of the editorial board, “none of [whom] shared the views expressed by Dr. Grandjean.”

Grandjean resigned in 2012, ending a positive relationship that began under founding editor Leon Golberg. “I thought if [McClellan] invited me, he thought my advice would be useful, but apparently this changed to a situation where it was useful to have my name on the masthead to justify this was a balanced journal.”

Like the journal he founded, Golberg’s career aligned closely with industry. A native of Cyprus who held academic positions in South Africa and Britain and spent the end of his career at Duke University, Golberg oversaw Critical Reviews from its inaugural issue in September 1971, published by The Chemical Rubber Co.

The journal was introduced as “the voice of reason” in an era of “chaos and turmoil.”

“Never before have so many regulatory actions been taken or proposed — some too late, others prematurely — that have bewildered the consumer and had a crushing impact on industry,” Golberg wrote.

That same year, a public health crisis unraveled when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a warning against diethylstilbestrol (DES) — a synthetic hormone used for decades by pregnant women to combat morning sickness and prevent miscarriages or premature deliveries — which Golberg had co-created in 1938. As many as 10 million people were exposed to DES before it was linked to a rare vaginal cancer and other fertility problems, spawning myriad lawsuits.

Golberg’s role in the DES debacle is less well known than his later achievements. They include founding the Chemical Industry Institute of Toxicology (CIIT), now the Hamner Institutes for Health Sciences, a research group “founded and funded by the chemical industry,” according to the Research Triangle Regional Partnership. He also jump-started the British Industrial Biological Research Association, a consulting firm whose clients include ExxonMobil and Procter & Gamble.

In the 1970s, Golberg consulted for a now-discredited campaign for “safer” cigarettes by R.J. Reynolds, which still funds fellowships in his honor at Wake Forest and Duke. He died in 1987 from mesothelioma, an aggressive cancer linked to asbestos exposure.

McClellan succeeded Golberg as both Critical Reviews editor and CIIT leader, working with trade groups like the American Chemistry Council. Critical Reviews has since become one of the most-cited toxicology journals, at the same time drawing a spate of criticism.

Ruff, the anti-asbestos advocate, chastised Critical Reviews in May for what she alleged to be improper disclosure in a 2013 asbestos article. Testimony in a court case stated that an industry group paid the authors nearly $180,000 in writing fees, which were erroneously described as “grants.” She cited the incident as a reason for stricter disclosure reporting and enforcement.

As Critical Reviews editor, McClellan has been outspoken against regulation. By his own count, he has testified before Congress 20 times. In 2011, he argued against a proposal by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to curb ground-level ozone, or smog, as too expensive, calling for lawmakers to recognize that “a healthy economy with people employed is the cornerstone of a healthy population.”

Industry ties

Since its 1981 debut, Regulatory Toxicology has billed itself as a credible and objective source for a broad audience. Its co-editors promised to focus on science instead of politics and “mythology.”

“Safety is relative, not absolute,” AIDS researcher Frederick Coulston and FDA scientist Dr. Albert Kolbye Jr. wrote in the inaugural issue. “Safety is a moving target.”

The journal has been sympathetic to industry from the start. In its first issue, an associate editor lamented: “There has always been a sense of competition between government and industry, but always a high degree of mutual respect. In the seventies that spirit changed from competition to an adversary posture and from respect to distrust.”

Regulatory Toxicology is the official publication of the International Society of Regulatory Toxicology & Pharmacology, an association whose leaders include a Coca Cola executive, corporate consultants and lawyers.

In an email to the Center, President Sue Ferenc denied that the society plays any editorial role at the journal. Outside of the society, Ferenc heads the Council of Producers & Distributors of Agrotechnology, a pesticide group with its own political action committee.

But significant overlap at both the society and the journal has existed for years.

Gary Yingling, a former FDA attorney who now represents industry clients, has been an editorial board member of Regulatory Toxicology since 1981 while also serving as the society’s general counsel. Fellow board member Terry Quill is an industry lawyer and former society president, who led the society’s push against labeling chloroform as carcinogenic. The EPA has since classified chloroform, a byproduct of chlorinating water, as a probable human carcinogen.

Recipients of the society’s achievement award include well-known journal figures like McClellan, the Critical Reviews editor who also sits on Regulatory Toxicology’s board. The society credited the journal’s growing popularity as the “major” source of its success and “esteem.”

Responding to questions about industry’s financial support of the society, then-president Christopher Borgert wrote in a 2008 newsletter, “Science has an objective means of evaluating information, but it has nothing to do with who got the money and why . . . The process of science removes the scientist, with his numerous biases and conflicts of interest, as far as humanely [sic] possible from the process of data generation and interpretation.”

Regulatory Toxicology’s editors have also made headlines. Chain-smoking through an interview with The Wall Street Journal in 1997, Coulston claimed nicotine wasn’t addictive and smoking didn’t cause cancer. In 2001, his New Mexico chimpanzee lab was stripped of federal funding amid animal abuse claims.

Gori became editor of Regulatory Toxicology following Coulston’s 2003 death and has also served as society president. In 2013, he and 17 other toxicology journal editors penned an editorial criticizing the European Union’s plans to regulate chemicals known as endocrine disruptors. Of the 18 editors, only one did not have industry ties.

‘All that noise’

“If a call comes in and the number is withheld, you might become suspicious and ignore the call,” Grandjean wrote in 2012. “Scientific authorship should be just as simple so that we can concentrate our attention on the sources we trust.”

But representatives of the EPA, the FDA and the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration said their agencies treat science equally, regardless of the funding source. Disclosure is encouraged by all three agencies but isn’t mandatory.

Speakers at FDA proceedings are asked to disclose relevant financial relationships but the agency doesn’t bar those who don’t comply from participating.

Science at the EPA and OSHA is evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Study authors are asked to disclose “funding sources and other pertinent interests” at the EPA, while OSHA asks those who comment on proposed rules to provide disclosures with their submissions.

What should or shouldn’t be disclosed is a matter of debate. “There is no agreement on what a conflict of interest is,” said Arthur Caplan, founding director of the Division of Medical Ethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center. “The disclosures currently say, ‘I’m going to disclose industry funding because that is a potential source of bias. You, reader, have to decide for yourself whether it is or it isn’t. Good luck to you.’ ” Current sentiment “demonizes the industry side,” Caplan added, while ignoring potential biases created by private foundations or government money.

Disclosure policies don’t exist to eliminate bias, said Sheldon Krimsky, a professor at Tufts University who studies science and public policy, but to allow the public to assess potential conflicts that can undermine findings. “Science is not a matter of this fact and that fact; there’s all sorts of nuance in science,” he said. “You can draw conclusions in science beyond what your data tells you.”

Krimsky’s own research has found that industry-backed studies typically yield findings that bolster a company’s bottom line. “Companies want you to produce a specific result,” he said. “They won’t publish it if you don’t.”

Even with proper disclosure, assessing a study’s credibility takes time, said the NRDC’s Sass. “In the end we still have to go through it on its merits; so do the EPA, and [other] federal bodies,” she said. “That leaves us with the task of addressing the substantive flaws each time, article by article.”

In the federal regulatory process, this can mean additional public hearings and meetings where activists go head-to-head with, and are often outnumbered by, industry representatives.

“The system can’t manage all that noise,” Caplan said. “The science tends to get lost and the politics wins or the economics wins. When there’s that much noise going on, other factors start to resolve the dispute and they’re not factual.”

Read more in Environment

Environment

‘It just ruined everything — the whole life’

Feeling abandoned by state regulators, hundreds of rural Pennsylvanians endure contaminated well water they blame on fracking

Environment

Hot mess: states struggle to deal with radioactive fracking waste

Potentially dangerous drilling byproducts are being dumped in landfills throughout the Marcellus Shale with few controls

Join the conversation

Show Comments

It is really interesting how having certain industry ties has called this journal’s authority into question. Personally, I would just look at the findings and the studies in the journal to see if they followed industry standards. If the studies being done are following current standards and are verified by professional toxicology consultants, then the data would speak for itself.