Introduction

Ted Latusek has black lung disease. For almost two decades, his breathing has been so bad he’s been considered totally disabled. Even his former employer, the coal giant Consol Energy, does not dispute those points.

Nineteen years after he first filed for federal black lung benefits, however, his case remains unresolved. What’s really causing his impairment, doctors testifying for Consol contend, is a completely different and unrelated disease. To win his case, the former miner must show that his disability is caused by black lung.

Though parts of his lungs show the dark nodules typical of the classic form of black lung, all doctors agree that his biggest problem is elsewhere, in the parts of his lungs that show severe scarring with a different pattern.

His case file, spread in piles, covers a conference table, but all of the medical reports, depositions, hearings, briefs and rulings center on one question: What caused the abnormal scarring that has consumed large portions of his lungs?

The fight over the answer to that question goes to the heart of the newest battle in a longstanding war between companies and miners. Latusek’s legal tussle is the signal case in the latest effort by the coal industry to deny emerging scientific evidence and contain its liabilities, a strategy that has played out repeatedly over more than a century and locked multitudes of miners out of the benefits system, the Center for Public Integrity found as part of the yearlong investigation, “Breathless and Burdened.”

Consol has hired radiologists, pathologists, pulmonologists and a statistician to examine Latusek, write piles of reports and attack a growing body of medical literature. His disease, they maintain, is a rare illness that appears in the general population and causes lung damage with the appearance seen in Latusek. The cause is unknown, but, they say, it definitely isn’t coal mine dust.

Yet medical evidence increasingly has shown his pattern of scarring to be a previously unrecognized form of black lung.

Broad recognition of the illness’ connection to coal mine dust could have significant financial implications for coal companies. The Center identified more than 380 benefits cases decided since 2000 in which the miner had evidence of this atypical presentation, and studies have shown the disease pattern to be present in at least 15 percent of some groups of miners examined.

Since Latusek first filed his claim in 1994, research increasingly has shown that coal and silica — the toxic mineral in much of the rock in mines — can cause the pattern of scarring he has. Government researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as well as other independent doctors, have linked the pattern to coal mining.

“It’s certainly related to their work,” said David Weissman, head of NIOSH’s division of respiratory disease studies. “We’re confident of that.”

Yet, while other variants of black lung are defined explicitly in Labor Department regulations, Latusek’s form is not, and doctors paid by the coal industry continue to testify that there is no evidence of any connection between mining and this form of disease. This leaves the complex medical issue to be argued case by case in the benefits system, which is often ill-equipped to address emerging science and typically favors coal companies and the well-paid consulting doctors they enlist.

A Labor Department spokesman said the agency doesn’t think a regulation formally recognizing the form of disease as a type of black lung is necessary. Current rules, the spokesman noted, allow miners to attempt to prove a relationship between their work and this variety of illness.

Experts interviewed by the Center, however, argued that explicitly stating such a relationship would lessen miners’ burden, pointing to a previous rulemaking as a model. In hundreds of cases reviewed by the Center, miners with a disease pattern like Latusek’s have faced particular challenges in proving their cases.

Latusek, a coal miner’s son who grew up in an area of northern West Virginia dominated by Consol, has won four times before an administrative law judge, but appeals courts have vacated or reversed the decision each time.

Consol did not respond to requests for comment.

While courts have grappled with the complexities his case presents, Latusek’s health has deteriorated. He has gone on oxygen and endured a lung transplant. The doctor who originally treated him on referral from Consol has testified against him twice, and many of the industry’s go-to consultants have weighed in.

Yet he and his lawyer — the daughter of a coal miner who has toiled more than half her career on Latusek’s case despite rules barring her from collecting a cent in fees until the case closes — press on.

“I know my case is going to set a precedent,” Latusek said.

“There is nothing in mining that makes it insanitary, and any insanitary conditions which may exist are doubtless closely related to the rum shop.”

John Fulton, engineer and coal industry representative, 1901

“Black lung” is not just one disease. Rather, it is a blanket term for a variety of lung diseases caused by breathing coal dust. As science has implicated coal dust as the cause of an increasing array of medical problems during the past century, coal companies have resisted, knowing broader recognition of the true effects of mining coal could place them on the hook for compensating more sick miners.

The coal industry’s reaction to the potential expansion of its liabilities has followed a familiar pattern. For more than a century, the industry has sought to keep a narrow definition of black lung.

In the early 20th century, coal companies and sympathetic doctors argued that coal dust was harmless and actually protected miners’ lungs from tuberculosis.

Since then, scientific advances have shown that breathing coal dust can harm different people in different ways.

One miner might develop the black nodules characteristic of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, the classic form of black lung. Another might find the air sacs in his lungs destroyed — emphysema — or the lining of his airways irritated and blocked — chronic bronchitis.

As the effects of coal dust have gained broader recognition, the industry in each instance eventually has had to accept the evidence. But, while these fights about classification have played out, sick miners have found it difficult, if not impossible, to win benefits.

Today, miners again are facing this strategy of denial and containment, this time over the pattern of scarring seen in the lungs of Latusek and hundreds of other miners with cases decided since 2000. In virtually all of the more than 380 cases identified by the Center, a doctor testifying for the coal company — or, in many cases, multiple doctors — blamed some variant of the disease idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, known as IPF, or a similar illness. This is the same scarring of unknown cause that Consol’s doctors say Latusek has.

Miners lost more than 60 percent of these cases. Even when judges awarded benefits, the decision often hinged on an issue other than recognition of the abnormal disease appearance as black lung. Numbers on the success rate of miners at this level in all cases were not available for comparison.

In many cases, judges credited coal company experts and reached medical conclusions that flatly contradict the views of NIOSH and NIH. Judges must rely on whatever evidence a miner can produce, and finding doctors who can rebut the vehement assertions of the company’s experts can be a challenge.

The particulars of Latusek’s case offer a rare and nearly ideal opportunity to isolate the key question that could affect the claims of many other miners: Does coal mine dust cause his form of disease? Latusek never smoked. He doesn’t have an autoimmune disease. He never underwent radiation treatment or took certain toxic drugs. He has no family history of the disease.

In other words, doctors can’t blame his illness on these other potential causes. What he does have is a history of intense exposure to the potent mixture of dust generated by the most powerful machinery of modern mining.

“There are no healthier men anywhere than in the mining industry.”

— Coal Age, trade journal, 1915

Latusek’s path to the mines was undeterred by the warnings of his father, who worked underground. “He never wanted me to go to the mines,” Latusek said. “He knew how dirty and dusty and dangerous it was.”

Aside from mining, though, there weren’t many well-paying jobs in the area of northern West Virginia, near the town of Fairview, where Latusek and his older sister grew up. Consol’s mines dotted the landscape, tapping the rich Pittsburgh coal seam; the company remains one of the nation’s top five coal producers today.

Latusek worked from the time he was 13, shedding his boyhood shyness as he carried out groceries from the local market and chatted up customers.

He breezed through high school, but found himself unprepared for the more rigorous workload at nearby Fairmont State University, especially with the two jobs he was working. After two years, he dropped out and went full time for a utility company that dug ditches and installed the power lines feeding into Consol’s mines.

When he was laid off, he applied to work for Consol. In September 1970, he went underground, handling a variety of jobs. “I worked there about three months, and then Uncle Sam said it was my time to go,” he recalled

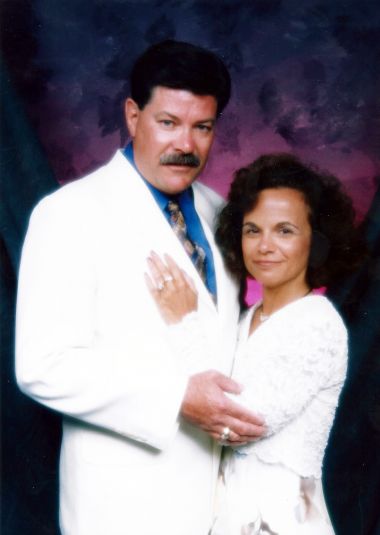

Drafted into the Army, he received training in electronics and ended up stationed as a technician at a satellite communication site in New Jersey. He narrowly missed being sent to Vietnam. In July 1971, he married Donna, whom he’d met while at Fairmont State, and, six years later, they would have a daughter, Jennifer.

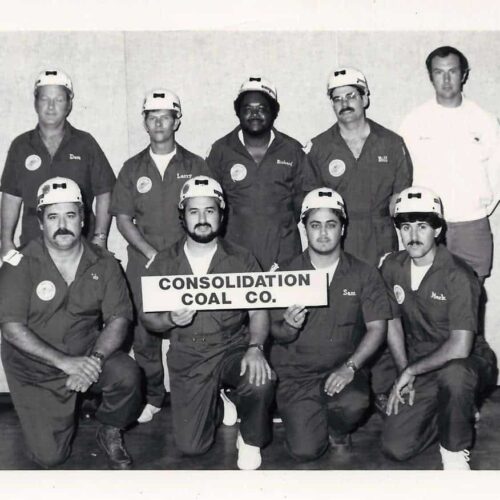

In December 1972, he returned to the mines. He quickly ascended the ranks, becoming a maintenance foreman and eventually longwall coordinator. This meant that, at 29, he was in charge of a crew running the massive moneymaking machine. A longwall’s spinning shearer can hollow out mountains in little time. Consol made sure everyone knew the value of production, Latusek said: Every minute the machine wasn’t running cost the company $12,000.

He took pride in motivating his crew, keeping his own logs of production and comparing them with those of other shifts. “We actually outmined the other crews two to one,” he said.

Before long, he was promoted again; the company placed him in charge of all the longwalls at two mines. He sometimes would travel to Great Britain to see the factories that manufactured the machines, and he was always on call, once working 78 straight days. Another time, he spent virtually an entire week underground, coming up for a couple of hours a day to shower, eat and sleep.

At times, he lived in clouds of dust, he recalled. The roof would cave in, and his crew would have to cut through rock for days on end. Or the exit would be blocked by falling rock, rendering any attempt at ventilation pointless. “A lot of times, you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face,” he recalled.

Latusek’s health problems first began to surface in 1989. He was short of breath, and he coughed constantly. A company physical turned up “one area of concern,” as Consol’s doctor put it, in 1990. The company referred him to a specialist, Dr. Joseph Renn III.

Latusek didn’t know it at the time, but Renn frequently testified for coal companies defending black lung claims. He would later abandon his private practice and start a consulting firm, working almost exclusively for companies defending claims of occupational lung disease.

Renn diagnosed IPF. The reasoning behind the diagnosis is one that Renn and other doctors have repeated in case after case: Black lung causes round scars concentrated in the upper lungs. Latusek had irregularly shaped scars concentrated in his lower lungs, a pattern characteristic of IPF and related diseases. This conclusion absolved Consol of responsibility for his serious lung problems.

Though Latusek continued to work, the amount of oxygen in his blood continued to drop; his lungs couldn’t transfer what he breathed in to his bloodstream. He struggled with any exertion and wheezed, especially when he was around dust.

While visiting a mine in Scotland in 1993, he had a moment of panic. He had to crawl 1,000 feet in an opening about four-and-a-half feet high. Halfway across, he lost his breath. “It felt like somebody had put a bag over my face,” he recalled. When he got back to West Virginia, he had another episode while walking the steep stairs exiting the mine.

Latusek, in an interview and in court testimony, recalled a conversation with Renn in which the doctor said there wasn’t much else he could do and he would likely die in a few years. Renn said privacy rules barred him from discussing Latusek’s case, but he added that it is standard practice for him to discuss potential outcomes with patients.

In a legal filing, Consol’s lawyer challenged Latusek’s recollection, saying there was no mention of a prognosis in Renn’s reports.

Not ready to give up, Latusek asked if there was anyone who could help him. Renn referred him to National Jewish Health in Denver, widely regarded as one of the nation’s top centers on lung disease. Latusek began flying to see Drs. Constance Jennings and Cecile Rose.

Jennings had studied IPF and similar diseases while at NIH, and, when she first examined Latusek, she wasn’t sure that she actually was looking at a case of the disease. It was 1993, and there had been little work on the potential connection to coal dust, but she had her suspicions.

In the report on her initial examination of Latusek in October, she noted that he had evidence of both classic black lung and IPF, then posed the question that would reshape his case: “Are the two processes related?”

“Someone could say peanut butter causes pneumonia,” Dr. Gregory Fino said in a February 1997 deposition. “Well, show me in the literature that there is a statistically increased incidence of that occurring, and then I will not prescribe peanut butter to anybody.”

Peanut butter was, in his analogy, coal dust, and pneumonia was the pattern of scarring in Latusek’s lungs. Fino was adamant that the medical literature showed no connection between the two.

“I can’t tell you what caused the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” he testified. “I can tell you what hasn’t caused it: coal mine dust employment and coal mine dust inhalation.”

“We are not informed of any occupational diseases in the mining industry.”

Ralph Crews, coal industry lawyer, before a federal panel, 1920

In recent decades, Fino has been perhaps the most high-profile among the cadre of doctors who testify regularly for coal companies. When a miner files a claim, he is entitled to an exam by a doctor from an approved list paid for by the Labor Department, but he also must submit to an exam by a doctor of the company’s choosing.

Consol chose Fino to examine Latusek.

Fino was the industry’s go-to doctor in the most recent battle over the definition of black lung. When the Labor Department proposed rules in 1997 to expand the list of illnesses potentially caused by breathing coal dust to include such diseases as emphysema and chronic bronchitis, the National Mining Association enlisted Fino.

Along with a biostatistician, he wrote a lengthy critique of the studies relied on by the Labor Department and said, “There is much bad science or loose terminology in these proposed regulations.” In 2000, the agency finalized the rules, rebutting Fino’s arguments in detail.

Fino and other doctors had testified regularly that smoking, not coal dust, caused these diseases that obstructed miners’ airways. The approach by Fino and other doctors in Latusek’s case was much the same — attack the science linking the disease to coal dust, identify an alternative cause.

Renn, for example, said of black lung and IPF, “There’s no literature that relates the two.”

Dr. W.K.C. Morgan, a veteran of previous battles over the definition of black lung dating to the 1960s, testified, “I think this is just wishful thinking.”

Consol’s lawyers hired a statistician to poke holes in the studies introduced into evidence by Latusek’s lawyer, Sue Anne Howard.

Unlike many miners, however, Latusek had a tenacious lawyer and doctors with impressive credentials on his side, too.

Howard has represented sick miners since she began practicing law in 1982. The first black lung case she handled was her father’s. She won, then watched him “die of black lung by inches,” she recalled. As the hours spent on Latusek’s case have amassed — time for which she’s been barred from collecting any fees — she’s tried to support her practice with other cases.

Jennings and Rose from National Jewish had become convinced that Latusek’s disease was caused by his job. They acknowledged that the science was still emerging but laid out a rationale for their conclusion. The way his disease struck early, then smoldered for years, was very abnormal for IPF, they said, and a tissue sample showed tiny mineral particles in the area of his scarring. Consol’s pathologists disputed this assessment of the biopsy evidence.

In a June 1997 decision, Administrative Law Judge Daniel Leland awarded benefits to Latusek. Consol’s lawyers appealed, and, though the Benefits Review Board upheld Leland’s decision, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit vacated the award in a divided opinion in 1999.

Referencing the studies introduced by Howard, the majority wrote, “At best, the articles offered tepid support for Dr. Jennings’s, Dr. Rose’s, and the [administrative law judge’s] conclusion.” The judges noted that Consol had more doctors on its side, and wrote, “Although we do not advocate counting the votes of various medical experts to reach a conclusion … [w]e believe that such a disparity of opinion merits attention.”

The dissenting judge chastised his colleagues for overstepping their authority and substituting their views of the medical evidence for those of the administrative law judge. “All we have here,” he wrote, “is a situation where two or three more experts on one side dispute the findings of two or three fewer experts on the opposing side.”

A 2002 law review article by Washington and Lee University Professor Brian Murchison singled out the decision as a “particularly disturbing” example of “judicial intrusion.”

The ruling sent the case back to the same administrative law judge for reconsideration. The case dragged on, with the judge awarding benefits twice more, before it again arrived at the Fourth Circuit. Again, the majority questioned the medical evidence, this time reversing the award. And again, the dissenting judge — not the same one as in the prior ruling — blasted his colleagues for overreaching. Nonetheless, the 2004 decision ended Latusek’s first claim.

Latusek was devastated. “My goal in life was to outlive Consol, to live long enough to know that I beat them in this case,” he said recently. “I thought that I had. I was on cloud nine. And then it goes to the Fourth Circuit Court, and they take it all away from me.”

“It doesn’t matter what the damn thing is called. The man can’t work, he’s disabled.”

Dr. I. E. Buff, cardiologist and advocate for miners, 1969

If Consol’s doctors were right, Latusek should have been dead before his case even reached the appeals court. Studies have shown patients with IPF typically die within five years of the onset of the disease. Latusek had first shown signs in 1989. Consol’s experts acknowledged this was unusual but said it wasn’t unheard of for some people to survive longer.

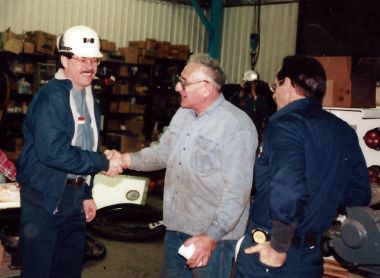

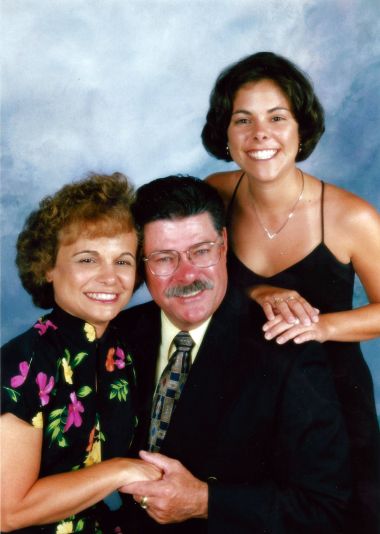

Courtesy of Ted Latusek

His age also raised questions. IPF rarely strikes people younger than 50. Latusek was 39 when his disease appeared.

Both of these characteristics — earlier onset and longer survival — were not unique to Latusek, as it turns out. Though this presentation would be abnormal for IPF in the general population, there is evidence that it is not unusual for certain people: miners.

As Latusek’s case progressed, scientific interest in IPF grew. “Few lung disorders have seen a renewed investigative focus like IPF,” according to a 2003 report prepared by a group of doctors for the American Thoracic Society.

The lungs have a limited number of ways to respond when they come under attack. One response is the pattern of scarring in the lower lungs that often is diagnosed as IPF. But there are many diseases that cause essentially the same pattern and have a defined cause.

Increasingly, research has identified more causes of this pattern. Thus, people with a disease that previously would have been classified as IPF now are diagnosed with a more specific illness.

One prominent cause that has emerged in recent research: occupational dust exposure. Studies have linked the IPF pattern of scarring to breathing fine particles of everything from metal and cotton to coal and silica.

The phenomenon does not appear to be new. A 2012 study by NIOSH epidemiologist Scott Laney and former NIOSH official Lee Petsonk noted that research showing an IPF pattern in miners dated to 1974 but had been largely overlooked. Addressing the often-repeated view about the typical appearance of black lung — one that would exclude an IPF pattern — they wrote, “the scientific foundation for this expectation is unclear.”

Analyzing 30 years of X-rays from the agency’s surveillance program, roughly half had a discernible pattern affecting only certain areas of the lungs in certain ways, they found. Of these, a striking 30 percent showed a pattern similar to Latusek’s.

As researchers have looked more closely, they’ve seen that evidence of the disease’s connection to coal mining — like the disease itself — appears to have been there all along. Studies in the 1970s and 1980s noted the pattern on X-ray and in tissue samples of coal miners. A 1988 study found the pattern on autopsies of between 15 percent and 18 percent of miners in South Wales and West Virginia and noted that the miners’ disease had struck earlier and progressed more slowly than IPF.

The most recent edition of a key medical textbook on lung diseases, released in 2005, describes the appearance of the pattern in miners and says, “It is important to be aware of this entity as many cases are inadvertently diagnosed as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.”

Earlier this year, a group of doctors described the pattern as a recognized form of black lung in a paper for an American Thoracic Society journal. “The spectrum of lung disease associated with coal mine dust exposure is broader than generally recognized,” the physicians wrote.

Doctors testifying for coal companies counter that this body of research is far from conclusive, saying it fails to show a direct causal relationship. And, they say, the studies failed to control for other potential causes, including smoking, or were skewed because participants were not randomly selected. Some of the same doctors made similar arguments in the 1990s about evidence connecting coal mine dust to diseases such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

“There’s no doubt that we need to learn more,” NIOSH’s Weissman said, “but the excess burden that you see in coal miners is much above what you would see in the general population. Even if we don’t know all of the exact details about how coal miners get that, I think it’s pretty clear that it’s associated with the unique exposures that they have.”

Former NIOSH official and current West Virginia University professor Petsonk said the evidence of the connection is becoming overwhelming. “It’s coming to the point where it will just not be controversial,” he said.

“The current norm is the contest of physician’s reports. If this exercise ever had a fresh, truth-seeking outlook, it has long since faded.”

Circuit Judge K. K. Hall, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, dissenting opinion, Grizzle v. Picklands Mather & Co./Chisolm Mines, 1993

A different story, however, is playing out in the benefits system. Just in cases decided since 2000, miners showing this pattern of disease have lost at least 236 times, a Center review of hundreds of cases found.

The administrative law judges who decide cases can find themselves in a difficult situation when a miner with a disease pattern like Latusek’s files a claim. A miner may not have access to a doctor who can argue persuasively — or who even knows — that the pattern can be caused by coal mine dust. Coal companies, on the other hand, have no shortage of doctors who argue emphatically and in great detail that there is no connection.

In several cases reviewed by the Center, the doctor who examined the miner on behalf of the Labor Department noted the IPF pattern but apparently didn’t consider the possibility it was caused by his work. In other cases, doctors offered equivocal opinions that, while perhaps scientifically responsible, were overwhelmed by the certainty expressed by company doctors.

In a pair of cases, for example, Dr. Donald Rasmussen, who typically testifies for miners, expressed basically the same view: The patient had evidence of an IPF pattern, which has many possible causes but is much more common in coal miners. This, combined with his breathing impairment and exposure history, made it likely that dust was the cause of his scarring.

One judge considered Rasmussen’s opinion “logical” and “well documented” and awarded the miner benefits. The other judge found it “not persuasive” and “not sufficient evidence of causation,” denying the miner benefits.

Coal company doctors, on the other hand, often provide categorical statements. In a case decided in 2004, Dr. Lawrence Repsher attacked the miner’s doctor, saying, according to the judge’s paraphrase, “Dr. James made up a heretofore nonexistent disease that apparently only Dr. James recognizes.”

In a case decided in 2007, Dr. George Zaldivar testified, “[Black lung] never has been linked with this kind of impairment and abnormality.” Dr. Kirk Hippensteel testified in a case decided in 2008, “It is a disease of the general public that isn’t precipitated by some … exposure to something like coal dust, silica dust.”

Each time, the miner lost.

Read such statements by coal company doctors, NIOSH’s Weissman responded, “Well, goodness, that would be a surprise to me.”

Former administrative law judge Edward Terhune Miller said he handled some cases in which a doctor testifying for the company called the miner’s disease IPF.

“I don’t like it,” he said. “When the doctor says, ‘I don’t know what it is, but it’s definitely not X,’ and he’s coming from a known direction, I confess I take it with a grain of salt. Now, whether or not in a written decision I can deal with it in some effective way is another question entirely because I’m not allowed to say, ‘That’s not a reasoned analysis.’ ”

Indeed, judges are barred from substituting their medical opinions for those of witnesses. They need the miner to present evidence to overcome the company doctors’ statements — a steep climb in a system where claimants are typically overmatched.

Before the Labor Department issued regulations in 2000 explicitly stating that diseases such as emphysema and chronic bronchitis can be caused by coal mine dust, company doctors frequently testified that these illnesses were never attributable to work in the mines.

Since 2000, most have changed their views. If they stick to their previous dogmatic assertions, a judge can give the opinion no weight. Doctors still can argue that smoking is a more likely cause in a particular case, but they cannot say coal dust is never a possible cause.

Miners’ lawyers say this has made it easier to win some cases, and numerous doctors interviewed by the Center said the Labor Department should issue rules to recognize explicitly that an IPF pattern can be caused by coal mine dust.

A Labor Department spokesman said such a regulation would be unnecessary because miners already can try to prove a link between the pattern and their dust exposure. Nonetheless, experts interviewed by the Center argued that formal recognition would set ground rules and help miners who didn’t have access to highly qualified experts who could attempt to draw such a connection.

“The law favors standards,” said Howard, Latusek’s lawyer. “Right now, with respect to [this form of disease], we have no standards. … It just becomes, unfortunately, many times a matter of which doctor writes a better report, not which doctor offers the right opinion.”

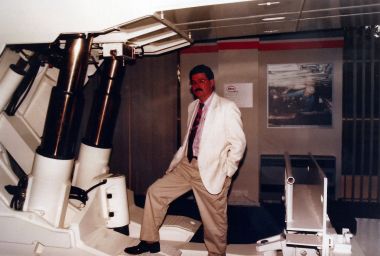

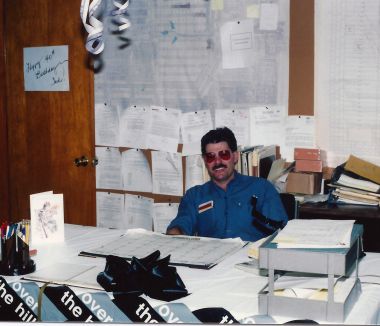

Courtesy of Ted Latusek

“Experts hired exclusively by either party tend to obfuscate rather than facilitate a true evaluation of a claimant’s case.”

— U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, Woodward v. Director, OWCP, 1993

Latusek was unconscious for the entirety of his 35th wedding anniversary. He awoke the next day, July 4, 2006, with a tube in his throat. He was confused, panicked. He tried to pull the tube out, but his arms were strapped down.

For two days, machines aided his breathing. When doctors removed the tube, they told him to take a deep breath.

“It was magic,” Latusek recalled. “I’d never felt air go in so easy. It was a beautiful feeling. I could actually breathe in deep. For years, I couldn’t do that.”

He had a new lung, thanks to an organ donor in Connecticut and a team that battled a malfunctioning airplane and torrential storm to get it to him.

The past few days had been frenzied. Latusek and his wife were in Pittsburgh to celebrate their anniversary. They were in bed at a hotel when someone from the hospital called at 12:15 a.m. — a lung had become available.

Throughout the morning and into the next day, nurses and doctors prepared him as they waited for the lung to arrive. At 7:30 p.m., they wheeled him into the operating room.

The lung, however, wasn’t there. It was supposed to be coming by plane, but the aircraft’s door wouldn’t close. It was moved to a helicopter, which was grounded en route by bad weather. An ambulance finally got the lung to Pittsburgh, and doctors worked throughout the night.

Latusek still had one bad lung, but he could breathe on his own again. For about a year, he’d needed an oxygen tank. Tests showed his lung function continued to decline.

His deteriorating health had put his pursuit of benefits on hold. On his behalf, Howard had filed a petition to modify the previous denial in January 2005, but, as his transplant grew imminent, progress had slowed.

As he recovered from the surgery, his case began to inch forward again. This time, Howard was armed with advances in scientific knowledge thanks to renewed interest in IPF.

Jennings had left National Jewish, so Latusek began to see Dr. James Dauber at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. He was director of a hospital unit that specialized in treating diseases such as IPF. Yet he, too, became convinced that Latusek’s scarring was caused by dust in the mines.

“In the last ten years, our thinking about [IPF and similar diseases] has undergone a tremendous transformation,” he testified in 2011. Rose noted in a deposition a few months later, “There’s a huge body of science that has emerged since 1995.”

Consol had no trouble finding experts who maintained the studies were preliminary and flawed.

Renn again insisted his former patient had a disease of unknown cause. By now, he was doing only consulting work and, according to his testimony five years earlier, charging $700 an hour. Asked during a deposition if Latusek’s scarring was related to breathing coal mine dust, Renn testified, “There is absolutely no scientific literature that would support that statement.”

He has given similar opinions in at least 30 cases decided since 2000, a Center analysis found. In an interview, Renn, who is winding down his consulting work and preparing to retire, said he now believes it is possible for coal mine dust to cause a pattern like that seen in IPF. He said he has made such a diagnosis, though he wasn’t sure when or how many times. The Center was unable to find any of these diagnoses in court records.

In the past decade, Dr. David Rosenberg has emerged as a primary consultant for coal companies and one of its staunchest debunkers of science related to the connection of coal mine dust and IPF. Rosenberg is an assistant clinical professor at Case Western Reserve University and is affiliated with the University Hospitals system in Cleveland.

In a 2012 deposition, Rosenberg described the volume of his work for coal companies, and conservative estimates of his fees approached $1 million a year. He testified he didn’t know how much he earned from the industry, but that it was “obviously a significant amount.”

In Latusek’s case, as in others reviewed by the Center, Rosenberg went study by study, critiquing each. One failed to control for smoking, he said. Others weren’t designed properly. Overall, the studies raised hypotheses but offered no proof of a causal relationship.

His conclusions went further. “We know that coal mine dust exposure doesn’t cause this condition,” he testified.

Rosenberg has offered a similar opinion in more than 60 cases decided since 2000, the Center found. In these cases, the miner lost about 60 percent of the time. Rosenberg did not respond to calls and emails requesting an interview.

Fino, who examined Latusek some 15 years earlier, was not involved in his second claim. In a recent interview, he said he didn’t recall the case but now believes it is possible that a disease pattern like Latusek’s could be caused by coal mine dust.

“I did change my opinion,” Fino said. “I go by what the medical literature says.”

He said he has made this diagnosis in some cases. The Center’s review of hundreds of court decisions did not identify any such cases, but did find about 100 decided since 2000 in which he diagnosed IPF or a similar disease.

In May 2012, Administrative Law Judge Thomas Burke awarded benefits, crediting Latusek’s doctors and the studies supporting their claims. This August, however, the Benefits Review Board delivered another setback. It upheld most of Burke’s decision but remanded the case, saying he needed to offer a better explanation of why he didn’t credit the opinions of two of Consol’s doctors.

“The first priority and concern of all in the coal mining industry must be the health and safety of its most precious resource — the miner.”

— First sentence of the 1969 Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act

Latusek has endured countless complications and indignities during his two-decade fight for benefits. Some drugs made his hair fall out or caused rectal bleeding. Others have caused severe depression and destroyed his kidneys, which will require a transplant in a few years.

A devout Methodist, he sees possible meaning in his suffering. What he can’t shake is a deep sense of betrayal.

For Consol, he put in 60- or 70-hour weeks regularly, sometimes more. The team he supervised in the 1980s brought out, on average, about $70,000 worth of coal per shift, he estimated. He’s undergone three knee operations and had two fingers reattached after machinery sliced them almost completely off.

He still has the article from a company publication highlighting a cost-saving discovery he’d made and pictures of him examining machinery for Consol in England or posing with fellow members of a mine rescue team. His email address still begins “Longwall.”

“I was loyal to the company,” he said, “but the loyalty wasn’t there for me.”

In 1994, after the company received a letter from Latusek’s doctors saying he needed to be moved to an above-ground job because of his health, his managers offered him a personnel job. It would have meant a longer drive and 40-percent pay cut, he recalled.

“I felt like somebody just put a knife in my gut,” he said. “I told my wife: ‘I can take the lung disease because a lot of that’s my problem. I went in that mine and ate that dust and knew better. I should have known better, but I thought I was invincible. But I always thought Consol would take care of me.’ ”

Now, his case is before an administrative law judge once more, likely to return to the Fourth Circuit court — a trip that could take years.

“If I live long enough to win this case and others that deserve it are awarded benefits because of it,” he said, “the suffering I went through would be all for the good.”

Read more in Environment

Breathless and Burdened

Senators push reform of black lung program that ‘failed’ sick miners

IMPACT: Citing a Center-ABC investigation, senator says government has ‘abiding obligation to right this wrong’

Breathless and Burdened

Johns Hopkins suspends black lung program after Center-ABC investigation

IMPACT: Prestigious hospital will review X-ray reading service.

Join the conversation

Show Comments