Introduction

Thirty-six years after federal overseers of safety at nuclear plants first recognized the serious risks of fires – when a candle ignited a major emergency at the Browns Ferry nuclear plant – preventable fire hazards still persist at the nation’s reactors, including Browns Ferry.

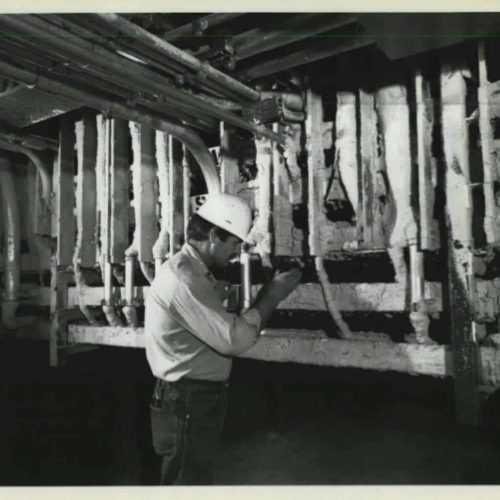

On Tuesday, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission was back at the site of the nation’s worst reactor fire, in 1975, this time to issue a rare “red” safety violation – considered a matter of “high safety significance.” A valve critical for reactor cooling in the event of a fire or other accident had failed.

The valve may have been inoperable for more than two years.

It wasn’t the first such problem at the reactor, though penalties are almost always lighter. A number of fire safety violations have been issued over the years.

One example, in 2003: The plants operators relied on an employee to trip critical pumps during a fire, even though that would require the worker to endure intense heat, heavy smoke and other hazardous conditions.

Another, in April 2010: Failure to protect critical cables from fire damage.

On Wednesday, the nonprofit news organizations iWatch News and ProPublica, in rare separate investigations, reached similar conclusions about the NRC’s seeming inability to effectively safeguard nuclear plants against fires, which have been occurring for many years at the nation’s 104 nuclear plants at a rate of nearly 10 times annually.

Both organizations cited numerous examples of regulatory breakdowns, and ProPublica focused on Browns Ferry, where the plant still doesn’t comply with requirements to protect cables.

Nationally, half the accidents that threaten reactor cores begin with fires that can start from something as simple as a spark or short in a cable.

At Browns Ferry, the fire began with a candle, which ignited a seal that happened to be highly flammable. As a result of that fire, nuclear regulators realized fires posed significant hazards at reactors and in 1980 put in place regulations designed to protect the equipment needed to safely shut down a reactor in a fire.

As both investigations concluded, since those rules went into effect nuclear utilities have been granted hundreds of exemptions and nuclear regulators have allowed countless safety issues to go unresolved.

Although the nuclear industry and NRC repeatedly stress that there has been no fire as serious as Browns Ferry, critics argue a major fire is only a matter of time – and a more likely risk.

Countless smaller fires have occurred, with some coming close to endangering the reactor core.

“The agency takes full credit for the grace of God,” George Mulley, who authored several critical reports about lax fire enforcement while chief investigator at the NRC’s office of Inspector General, told ProPublica.

As iWatch News reported in its investigation, both regulators and the industry have routinely downplayed the risks of fire.

“The phrase `it can’t happen here’ has been a harbinger of trouble in the nuclear industry,” Peter Bradford, an NRC commissioner during the Three Mile Island accident who now teaches about nuclear power and public policy at Vermont Law School, told iWatch News. “Specific accidents don’t repeat themselves. Failures of reactor owners and regulators to anticipate and defend against remote but not impossible contingencies do.”

The risks posed by fires have been heightened since the accident at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi facility in March. That issue was raised again Tuesday when NRC chairman Gregory Jaczko toured the Indian Point nuclear plant on the Hudson River 35 miles north of Manhattan.

Critics of the plant, which is applying to have its operating license extended for another 20 years, have argued that it is vulnerable to earthquakes, is an attractive target for terrorists – and that it fails to meet many fire standards set by the NRC. iWatch News also reported on a little-known threat at Indian Point: the presence of two half-century old natural gas lines located 600 feet from the reactor containment building.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman, in a petition to the NRC asking for a review of all public safety threats posed by the plant prior to relicensing, noted that Indian Point has been granted over 100 exemptions to fire safety rules.

Indian Point, said Jaczko during his visit, meets “very stringent safety and security requirements.”

At the conclusion of his tour, Jazcko was asked about the presence of the natural gas lines. Safety critics have noted that the owner of Indian Point, Entergy Corp., and the NRC have routinely dismissed the threat a fire or explosion at the gas line would pose to the safety of the reactor.

Jazcko said he was aware of the gas lines, and a review by the NRC is underway.

“If there’s a safety issue there, we’ll take the appropriate action,” he said.

Read more in Environment

Environment

Fact Check: Permitting some fudging on oil stats

Obama official, defending pace of drilling approvals, cites data selectively

Join the conversation

Show Comments