Introduction

These articles were produced by the San Francisco Public Press.

Instead of being kicked out for fighting, stealing, talking back or other disruptive behavior, public school students in San Francisco are being asked to listen to each other, write letters of apology, work out solutions with the help of parents and educators or engage in community service. All these practices fall under the umbrella of “restorative justice” — asking wrongdoers to make amends before resorting to punishment.

The program launched in 2009 when the Board of Education asked schools to find alternatives to suspension and expulsion. In the previous seven years, suspensions in San Francisco spiked by 152 percent, to a total of 4,341 — mostly African Americans, who despite being one-tenth of the district made up half of suspensions and more than half of expulsions. This disparity fed larger social inequalities: two decades of national studies have found that expelled or suspended students are vastly more likely to drop out of school or end up in jail than those who face other kinds of consequences for their actions.

“My first act as a school board member was to push a student out of his school,” recalled Jane Kim, a former community organizer who as a member of Board of Education needed to approve all expulsions.

“That’s not what I expected to do,” she said, especially when it seemed to exacerbate the social inequalities she had pledged to fight in her position. Board colleague Sandra Lee Fewer said, “Sixty percent of inmates in the San Francisco county jail have been students in the San Francisco public school system, and the majority of them are people of color. We just knew we had to somehow stop this schoolhouse-to-jailhouse pipeline.”

Fewer and Kim, along with colleague Kim–Shree Maufas, led the three-year process for the board to officially adopt restorative justice. Though the task force charged with implementing the policy received only modest funding, expulsions have fallen 28 percent since its inception. Less serious cases have shown even more success. Non-mandatory referrals for expulsion (those not involving drugs, violence or sexual assault) have plunged 60 percent, and suspensions are down by 35 percent.

Board members and many educators say restorative practices have kept students in school and out of the criminal justice system. “We’re holding kids more accountable than we did before,” said Kim, who now serves on the city’s Board of Supervisors. “In restorative justice, you have to actually have the offender and the victim sit down and discuss what happened and how the offender can make it better.”

But the data — along with interviews with parents, students and educators — reveal that progress so far is halting and uneven. Critics say that’s because the transition from punitive to restorative justice is underfunded and haphazardly evaluated. Suspensions and expulsions are actually rising in some schools that have yet to embrace restorative practices, often in low-income, high-crime neighborhoods. At one, Thurgood Marshall High School, suspensions have almost tripled since 2007. The resulting picture is a school-by-school patchwork, at best an unfinished project to reform the traditional juvenile discipline paradigm.

One school’s quick turnaround

“In the past, we defaulted to the most expedient thing,” said Kevin Kerr, principal of Balboa High School in San Francisco. “Student behavior is incorrect, student gets suspended — not really fully thinking through the process and asking whether this is a good educational decision for this particular student.”

The tide began to turn in 2009, the same year Kerr took over as Balboa’s principal. That is when the San Francisco Board of Education dissolved the district’s discipline task force and created a new task force charged with implementing restorative justice.

“The biggest question anyone can ask in public education is, ‘Why? Why do you keep doing that?’” Kerr said. At Balboa, the policy change triggered an intense school-wide discussion among staff about how to deal with student misbehavior. Within two years, the school cut expulsions and suspensions in half as it turned from punishing misbehavior to embracing restorative practices.

Though he faces severe budget constraints and rising academic demands, Kerr concluded that restorative justice “may solve all the other problems, by creating a disciplinary policy where students feel that they always have a voice in the process, whether they committed a crime or were the victim of a crime.”

His faith in the new approach is based in part on the results documented in a growing number of school districts across the country. In 1994 the Minnesota Department of Education was the first to embrace restorative justice. At least two rigorous evaluations — one published by the department in 2001, and another this year at the University of Minnesota — found that these practices increased both the safety and academic performance of schools.

In the Bay Area, three researchers at the University of California-Berkeley’s School of Law studied the impact of restorative practices at Cole Middle School, a predominantly minority and low-income school in West Oakland. Their December 2010 study found that suspensions dropped 87 percent. Both students and teachers reported that the program made the school “more peaceful, with fewer fights among students and better behavior in the classroom, relative to earlier years.”

San Francisco’s efforts may be the most ambitious yet — and the immediate results especially promising, given the district’s deep budget cuts and the complexities of operating in one of the nation’s biggest, most diverse cities. They stem from a local culture that has already embraced restorative justice in law enforcement.

“Restorative justice recognizes the crime hurts everyone — victim, offender and community — and creates an obligation to make things right,” said Sunny Schwartz, who in 1997 founded an influential restorative justice program for violent offenders in the San Francisco County Jail, one of the first in the nation. According to an independent evaluation published in 2001, Schwartz’s program virtually eliminated in-jail violence and cut re-arrests for violence by 83 percent. When the San Francisco Board of Education considered adopting restorative justice in the schools, it sought her expertise.

Today, Kevin Kerr has pinned to his bulletin board a list of five “restorative questions” to ask students in trouble. The last and most important one asks, “What do you think needs to be done to make things as right as possible?” It’s a question educators like Kerr are asking themselves as they struggle to reverse what they see as a decade of damage from punitive school policies.

Difficult in practice

Only the most serious discipline cases ever reach Kerr. Day-to-day discipline is handled by his dean of students, Kathleen Rodriguez.

Rodriguez first encountered restorative justice three years ago while working at George Washington High School, when trying to resolve a problem between a teacher and three boys who became increasingly disrespectful and defiant in class.

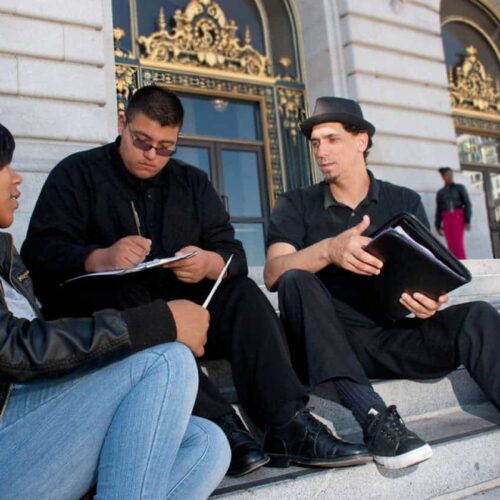

For help, she looked to Peer Courts, a city-funded restorative justice program that trains students to run hearings for offenders — or “respondents,” in restorative justice parlance — who have committed misconduct that ranges from chronic defiance to theft to fighting.

As coordinator Tony Litwak hastened to say, the Peer Courts do not judge guilt or innocence. Instead, he said, they try to identify who was hurt by the crime and then help respondents to make things right.

“It was quite a process,” Rodriguez said. “It took a lot of time.” Litwak and Rodriguez interviewed the teacher, talked with the boys, met with the parents and recruited a trained peer volunteer to run the hearing. The boys listened to the teacher and at the end of the process were asked to explain, in their own words, the teacher’s responsibilities and the effect of their behavior on the class. They wrote a letter of apology and performed community service with the teacher. Afterward, Litwak and Rodriguez worked with the parents to make sure the students consistently improved their behavior in class.

Other Peer Court cases are more nuanced and involve a combination of punitive and restorative approaches. In cases of violence or theft involving multiple kids, the perpetrators most responsible might be expelled and go through the juvenile justice system, while more peripheral participants face a court of peers.

When Rodriguez went to John O’Connell Alternative High School, she integrated the program into the life of the school, which faced significant disciplinary problems. Rodriguez was once even physically attacked by a student who refused to stop talking on her cell phone during class.

The main benefit of Peer Courts, Rodriguez said, is that it helps both the volunteers who run the hearings and the kids in trouble to take responsibility for the process. “You could see the volunteers go from not so sure to being amazing, developing their leadership skills,” she said. “The magic of Peer Court is the interaction of peer leaders with the offenders, who respond to their influence and become more aware of the harm done.” This, she said, makes for better outcomes and more lasting impact than simple punishment, or even other restorative programs led by adults instead of kids.

This complex process stands in contrast to the “easy and short punitive system that’s in place now,” Litwak said. He said that students “who do enter the traditional justice system never answer to their peers and are almost always advised by their attorneys to not discuss the incident. They are also denied the ability to apologize and make amends to victims and their family members.” Part of the reason the process takes so long, he said, is that it tries to build the empathy, compassion and community to strengthen the student and the school.

“Nobody is letting anybody off the hook,” Kerr said. “Whenever we have one of these restorative justice sessions, the perpetrator inevitably walks out of the room crying. That’s not our goal, but it’s just natural. We’re human beings, we’re going to have a sense of compassion for this person that we harmed, once we have a chance to see how our actions made them feel.”

Restorative justice is also implemented directly in classrooms, in the form of “circles” in which students talk through problems before they get out of hand.

“The teacher doesn’t yell or send anyone out of class,” said a student at Everett Middle School, one of the district’s three demonstration schools for the program. “Instead we circle up and everybody gets a say in how to fix it.” He added: “It’s boring, most of the time, but it’s better than everybody being angry. That’s how it is in my house.”

Some kids still get kicked out of school. On the week Kerr and Rodriguez were interviewed for this article, they suspended one student and referred another for expulsion — one who had previously gone through a restorative process, to no effect. The difference for Kerr and Rodriguez is that they now see punishment as the last, not the first, resort.

Every expulsion involves a serious crime, and often the expulsion process works in tandem with a legal one. Once expelled, a student might, depending on the case, be assigned to attend the Civic Center Secondary School, which handles the district’s hardest cases, or to attend a court-ordered school like Walden House, Woodside Learning Center or Log Cabin Ranch, most of which are operated by the Juvenile Probation Department. The worst-case scenario is that the student drops out and never comes back.

Shawn Taylor is the youth transitional services coordinator for the Seneca Center, which works with kids in court-ordered schools to help them get their lives back on track. He said he believes in “graduated sanctions” for misbehavior, but the problem is that simple expulsion can push them further away from school and towards life on the street.

“There’s no carrot for the kids,” Taylor said. “All they see is the stick. There’s nothing for them to strive for. Most of them have never been asked, never been taught by teachers or parents, to be a different type of person.” Whatever its limitations, he said, restorative justice at least tries to do that.

Expensive proposition

Restorative justice is not without enemies in San Francisco. Its deadliest foe is funding. Over the past two years, San Francisco’s school district has been forced to cut $133 million from budget, leaving it with $577 million this year.

As a result, the task force charged with the transition from punitive to restorative justice was allocated $664,763, a modest amount given the size of the system and the ambitious goals of the program. To date, the task force has trained staff at fewer than one-quarter of the district’s 107 schools. In fact, neither Kerr nor most of his teachers have received any formal training in restorative techniques. Instead they have embraced the initiative on their own. A significant portion of the task force budget goes to consultants and paying for substitutes while the teachers are in training.

Budget constraints also apply to independent nonprofits that provide restorative justice services and expertise. After the Board of Education embraced restorative justice in 2009, experienced, successful programs like Peer Courts did not receive additional funds or expand. Peer Courts received $100,000 from the city this school year, which “is basically our total program budget,” Litwak said. This year, Litwak will work with 50 students, the same number of students he did in 2008.

To Lisa Schiff and Tim Lennon, the lack of financial commitment calls into question the district’s ability to deliver on the promise of restorative justice. The two are spouses and longtime leaders in Parents for Public Schools and the parent-teacher associations at the schools their two children attended.

“The trouble is that they have $600,000 to address a $10 million problem,” Lennon said.

Thanks to budget cuts, Schiff added, “There’s been no rigorous analysis to say what kind of impact this program is really having. That’s too bad, because during a time of competing resources, we want to be able to defend programs that are working or change them to be more effective. You can’t do that without good data. And unfortunately, in this case, the lack of analysis and planning means that kids are getting physically hurt,” she argued, because violent offenders are not dealt with effectively.

The district acknowledges the program’s challenges but says it has made progress in two years. In the 2010-2011 school year, it trained 823 employees, including the entire staff at three demonstration schools. This year, said Kerri Berkowitz, San Francisco Unified’s restorative practices coordinator, 35 schools have requested on-site training — something she is hard-pressed to provide.

“Our capacity right now is a challenge,” Berkowitz said. “Our team is made up of myself and a coach, and we’re hiring another full-time coach. Plus, there’s very little time in the school day — teachers don’t have very many professional development days, and we need funding to hire substitutes so that teachers can leave their classrooms. We have some money, but it’s not enough.”

Some schools late adopters

Berkowitz has never conducted training at the 769-student Thurgood Marshall Academic High School, which could use her help. Suspensions there jumped from 115 in the 2006-2007 school year to 315 last year, while they were falling across the district.

Thurgood Marshall is located in the Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood, where 30 percent of families make less than $10,000 a year. Homicide is the leading cause of death for children in the neighborhood, according to the Hunters Point Family social service agency. That statistic hit home when Thurgood Marshall student Andy Zeng was killed and mutilated in April. Two other neighborhood teenagers are accused.

As in many schools throughout the district, poverty and punishment go hand and hand. When Edgar Ulu, a student at Thurgood Marshall, was suspended in 2009 for fighting in the lunch line, he was taken to the principal’s office and suspended for one week. Edgar said there was no effort to discuss the incident or repair any damage done to the other student or the school — he was simply sent home.

In his case, at least, suspension worked. “I learned my lesson,” he said. That week he cut off his abundant Afro, a symbolic step intended to convey his desire to get serious about school. He graduated in 2011 and is now attending San Francisco City College.

“Thurgood’s a good school,” said Edgar, who as a linebacker was named to the high-school All-City team. “It’s just that they don’t have a football field, they don’t have enough extracurricular activities. Kids don’t feel connected.”

Administrators at Thurgood Marshall did not respond to requests for interviews.

The Board of Education’s resolution to adopt restorative justice did not force schools to adopt the practices, though rates of expulsion and suspension are now part of how the Board evaluates the performance of principals. Instead, the resolution funded a plan to gradually introduce the concept and train the staffs over a period of many years. In the meantime, deans, principals and teachers still have wide latitude in how they deal with disciplinary issues. District officials said the idea of diverting students from punishment spreads incrementally and varies school by school, social worker by social worker.

“The challenge is that at some schools there are only pockets of belief in restorative practices,” said Claudia Anderson, executive director of Student Support Services for San Francisco Unified. She is the district’s chief expulsion officer and leader of its restorative justice efforts. “If students continue to make inappropriate choices, then there’s a lot of pressure to fall back on traditional responses like expulsion.”

Even when administrators implement restorative practices, the staff sometimes botch the process, and parents sometimes resist.

Two parents, who asked that their names not be used to protect the privacy of their middle-school daughter, said that when their daughter was attacked by two other girls in an assault they described as “life threatening,” they were “pressured” to go through a restorative process that required the girl to face the classmates who assaulted her — a terrifying prospect. Ultimately, after requesting a more traditional disciplinary response to the attack, the family decided to leave the school, while the offenders remained. The family reported feeling victimized twice: by the attack and by the restorative process, which they said resulted in no consequences for the attackers.

“In restorative justice, the total focus is on re-integrating the perpetrator,” said the father. “But too often it comes at the expense of the victim.”

The district’s Claudia Anderson is not daunted. “There’s always going to be criticism,” she said. “For a decade we went through this zero-tolerance era. And quite frankly it didn’t work. It didn’t make one bit of difference.” The results so far suggest that the San Francisco experiment, while just getting started, could bear fruit if given the resources and time the staff need to develop it.

These conversations are happening all across the country. Nancy Riestenberg has coordinated restorative justice efforts in Minnesota public schools since 1994, which gives her a long-term perspective on the challenges facing San Francisco teachers and administrators as they ramp up the program.

“The research said that it takes three to five years to implement anything in schools,” Riestenberg said. “So everyone in San Francisco should take a deep breath and proceed as calmly as they can. You’re building a new system because the old system wasn’t working. And that’s to be applauded.”

Read more in Education

Juvenile Justice

Minor offenders, major consequences

Why Wisconsin’s justice system continues to treat 17-year-olds as adults

Juvenile Justice

Expulsion overturned for boy at heart of Center probe

County board of education says slap on the rear doesn’t merit harsh punishment

Join the conversation

Show Comments