Introduction

Mitt Romney takes a hard line against congressional earmarks, but the GOP presidential front-runner had a more favorable view of federal pork-barrel spending when he was governor of Massachusetts.

Under his leadership, Massachusetts sought tens of millions of dollars in earmarks for transportation projects through the state’s congressional delegation.

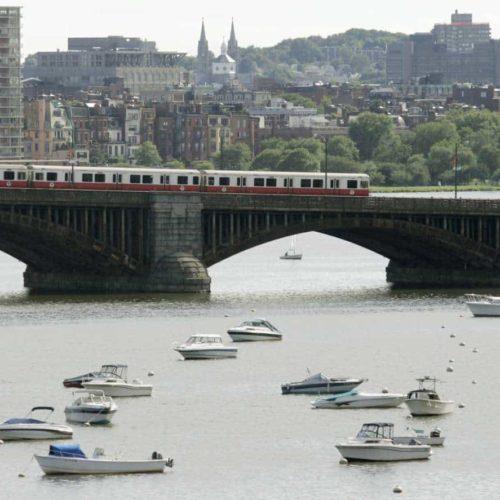

A prime example was the $30 million that the Romney administration requested to renovate the historic Longfellow Bridge that spans the Charles River between Cambridge and Boston. The landmark is seen in many movies and television shows.

Romney’s transportation secretary, Daniel A. Grabauskas, asked the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee to include the money in a transportation spending bill. That bill was full of thousands of earmarks that sparked public furor and became a symbol for Washington’s out-of-control spending when Congress passed it in 2005.

In a letter June 17, 2004, to the transportation panel’s chief of staff that was obtained by The Associated Press, Grabauskas said federal money for the Longfellow Bridge could be provided as part of the “bridge program, a new mega-project or an outside earmark, or a combination of the three.” Grabauskas did not immediately respond to phone messages from AP seeking comment.

A Romney campaign spokeswoman would not respond to questions about how many earmarks the Romney administration asked for, the amount of money involved and the particular projects.

“Every state budget in the country is dependent on federal funding, and every governor in the country makes requests for funding, but governors do not get to decide how Congress appropriates money,” said Andrea Saul, a Romney spokeswoman. “Gov. Romney supports a permanent ban on earmarks, which are symbols of what’s wrong with Washington.”

When Romney was governor and his state was desperately seeking federal dollars to repair crumbling roads and bridges, his administration suggested earmarks for projects to lawmakers on Capitol Hill who were in a position to request the money.

Romney officials specified projects they wanted included as earmarks in the transportation bill to members of the Massachusetts congressional delegation as the measure moved through Congress, said Rep. Jim McGovern, D-Mass.

“The Romney administration was crystal clear on earmarks and what they wanted,” McGovern said. “They sent us a letter specifically asking for money to be earmarked for projects.”

McGovern cited a Feb. 7, 2005, email from Tom Lawler, Romney’s deputy director of state-federal relations inWashington, to a senior McGovern aide seeking $50 million for the Charles M. Braga Bridge between Somerset and Fall River, and $25 million for a highway interchange on Interstate 495 in the Worcester Democrat’s district.

The Romney aide wrote in the email that the projects were “the state’s suggested high priority projects” for McGovern’s district.

The term “high priority project” is congressional jargon for an earmarked project, said McGovern, who did not pursue earmarks for Romney’s suggested projects.

Rep. Michael Capuano, D-Mass., a committee member who is the delegation’s leader on securing money for bridges and roads, said he was also approached by Romney officials asking for earmarks.

“It was a routine thing,” Capuano said. “They went to different members in the delegation. They came to me and said, ‘Here’s what we need.’ They didn’t do a ton of (asking for earmarks), but they did enough of it.”

Capuano said he supported the Longfellow Bridge project and secured a $3 million earmark for it after sending a request letter and form to the House committee.

Massachusetts sorely needed money for long-neglected major road and bridge repairs during Romney’s governorship because for years federal transportation dollars were sucked up by the massive Big Dig project that buried Interstate 93 in tunnels underneath downtown Boston.

Massachusetts, which had its own office of state-federal relations in Washington under Romney, also relied on lobbyists O’Neill and Associates, headed by the son of legendary former House Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, to help steer federal dollars to the state.

Romney joined the state’s big construction companies and contractors at a big Boston fundraising event in 2003 honoring Rep. Don Young, the Alaska Republican who at the time was chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee and who held powerful sway on spending matters as the big transportation bill moved through Congress. Young netted more than $50,000, according to a Boston Globe story at the time.

During his campaign, Romney plays up his anti-earmark views to try to convince GOP voters of his conservative values and to try to undermine his rivals’ claims of fiscal conservatism. Earmarks are a hot issue in the GOP race, particularly among conservatives angry about runaway spending and the big federal budget deficits.

Romney’s campaign and his allies have hammered rivals Newt Gingrich, a former House speaker, and Rick Santorum, a former representative and senator from Pennsylvania, as “prolific earmarkers” winning federal money, and he has called for a permanent ban on earmarks.

Romney stepped up his attacks after losses to Santorum in in Minnesota, Colorado and Missouri, branding Santorum as a big-spending Washington insider.

“A lot of us feel that the Republican Party lost its way in the past,” Romney said Wednesday. “Republicans spent too much money, borrowed too much money, earmarked too much, and Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich have to be held accountable.”

“Obviously, some of the things of his record are troubling … The fact that while he was in Washington, government spending grew by 80 percent. And the fact that he is a defender of earmarks. Look, I’m in favor of a ban on earmarks,” Romney said of Santorum in a Fox News Channel interview on Thursday.

The Santorum campaign, jabbing at Romney’s past support for federal spending, has highlighted a 2006 radio interview with Romney about the Big Dig where he said: “I’d be embarrassed if I didn’t always ask for federal money whenever I get the chance.”

Earmarking is the longtime Washington practice in which lawmakers, often at the request of governors and state legislators, insert money for home-state projects such as road and bridge work into spending bills. After the 2010 elections, Congress placed a moratorium on earmarking, following public outrage over a 2005 transportation bill stuffed with money for thousands of pet projects, including the infamous “Bridge to Nowhere” in Alaska.

Romney now has joined the chorus of tea party backers and fiscal conservatives who say lawmakers treat taxpayer money like a slush fund.

A pro-Romney group targeted Santorum with ads in recent primary contests assailing his support for pork-barrel spending in Congress. The Romney campaign has used a small group of House Republicans considered fiscal conservatives to attack Gingrich’s earmarking.

By Associated Press writer Andrew Miga.

Join the conversation

Show Comments