Introduction

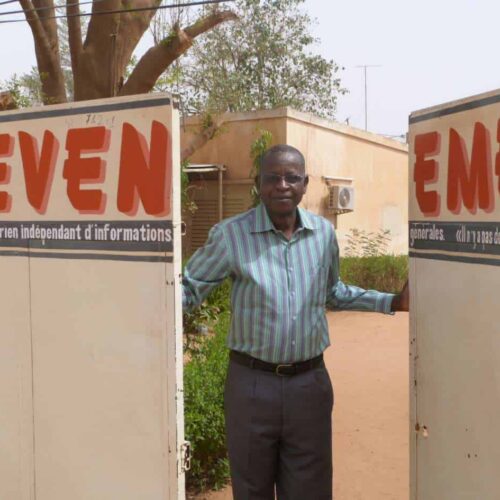

In late July, Moussa Aksar, the director of Niger’s L’Évènement newspaper, answered his phone and heard a familiar voice warning him that he was, once again, in danger.

“Be careful,” a friendly source told Aksar. “Look out for yourself and be careful what you say on the phone.”

Aksar had just published Niger’s first exposé from the Panama Papers, the investigation based on a leak of documents from a law firm that has helped politicians, oligarchs and fraudsters create and use secrecy-veiled shell companies.

The July 25 edition of Aksar’s newspaper featured a front-page story highlighting previously unknown details regarding an offshore company linked to a businessman reputed to be a major financier of Niger’s ruling political party. Copies of the paper sold out within hours.

Many citizens were delighted by the revelations. Others took aim.

“Moussa Aksar is reportedly hiding,” one Facebook user wrote, accusing Aksar of being wanted by the police for his reporting. “Has he lost his ability to make up fake stories?” laughed another. Another accused him of blackmail. Aksar suspects he was followed. He told his two daughters to lock the door and to unleash the family’s guard dogs.

Aksar and his newspaper aren’t alone among the journalists and news outlets that have been hit with blowback in response to their work on the Panama Papers investigation, the largest collaboration of journalists in history.

Even as the Panama Papers disclosures have sparked 150 official investigations in at least 79 countries around the world, they have also provoked pushback from individuals and governments displeased with revelations of the hidden economic holdings of the global elite. Politicians, business executives and thousands of their supporters have responded with vitriol, threats, cyberattacks and lawsuits, according to a survey by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which coordinated the Panama Papers investigation.

These hardline reactions are part of a continuing pattern around the world of threats and suppression targeting journalists, like Aksar, who fight to tell uneasy stories. Niger authorities jailed Aksar for six days in 2008, for example, for his reporting on corruption and trafficking in fake medicines and black market babies.

“We are tracking the impact of Panama Papers and the retaliation journalists and media organizations are suffering,” said Courtney Radsch, advocacy director at the Committee to Protect Journalists. “Sadly, we find it par for the course that journalists are under attack for reporting on corruption. We know that it is one of the most dangerous beats for journalists.”

One of the most unexpected flashpoints to emerge from the Panama Papers is in Spain where Grupo Prisa, the parent company of major newspaper El País, announced plans to sue ICIJ’s media partner, El Confidencial, for $9 million. According to El Confidencial, Grupo Prisa acknowledged the accuracy of El Confidencial’s reporting but claimed that the Panama Papers revelations that tied an offshore company to the ex-wife of Grupo Prisa’s chairman, Juan Luis Cebrián, amounted to unfair competition.

Cebrián’s ex-wife linked the company to Cebrián’s business and said that she had no role in its operations, a claim Cebrián denies. Both newspapers are fighting for the top spot in Spain’s news market. El Confidencial reported that Grupo Prisa claimed it lost readers and suffered economic loss because of El Confidencial’s reporting on the Panama Papers. Grupo Prisa declined to respond to ICIJ’s questions and said it is “in the lawyers’ hands.”

“The editor of the biggest newspaper and the biggest radio station in Spain is shamefully starring in the largest and most unprecedented attack on press freedom in our country,” El Confidencial wrote in an editorial in October. If the suit is successful, El Confidencial’s editor, Nacho Cardero told ICIJ, “this suit would mean that journalists can’t write or investigate about other editors or journalistic companies” no matter the level of public interest.

More than 400 journalists from more than 80 countries have collaborated on the Panama Papers investigation. Backlash against members of the reporting partnership has surfaced in nations where media crackdowns are common and in nations with reputations for high levels of press freedom.

- In Tunisia, unknown hackers brought down the online news publication Inkyfada. In Mongolia, a former environment minister sued MongolTV for libel — and lost.

- In Turkey, a newspaper partner in the investigative collaboration, Cumhuriyet, reported that a construction and energy executive with connections to President Recep Tayyip Erdogan telephoned to lash out at the paper for publishing his photo as part of its Panama Papers coverage. “You put my face on the front page, have you no shame?” the business mogul said, according to Cumhuriyet. “I will fight you …. You sons of bitches, don’t make a killer out of me.”

- The Finnish tax authority threatened to raid journalists’ homes and seize documents, an unprecedented move in Finland’s liberal media environment. Authorities backed down following protests. Finnish broadcaster YLE has filed a court appeal in an effort to definitively nix the tax authority’s ongoing demand for information.

- Staffers at La Prensa, a daily newspaper in Panama, were threatened by anonymous Twitter users. “What does it feel like to destroy your country?” asked one. Another tweet, liked and commented on by Ramon Fonseca, a co-founder of Mossack Fonseca, the Panamanian law firm at the heart of the scandal, featured a photo of La Prensa employees above the comment: “This is an act of high treason to the country to which they were born.”

- One online poll asked whether the best way to handle the “traitorous journalists” was to send them to jail or dump them in the Bay of Panama. For months before and after the project’s release, reporters were assigned armed bodyguards who posed as their Uber drivers.

It wasn’t the first time La Prensa had to enact security protocols, said La Prensa’s deputy editor-in-chief, Rita Vásquez. The paper’s editorial team, which objected to the title “Panama Papers” and to the way some European governments later singled Panama out, said the fallout put the newspaper in one of the most difficult positions in its history.

- In Ecuador, displeasure with Panama Papers went to the top. On April 12, President Rafael Correa used Twitter to name several journalists who worked on Panama Papers. Correa’s supporters followed up to harass the journalists for more information amid accusations that journalists’ decisions about which names of Ecuadorians to publish were politically motivated.

Correa’s tweet was retweeted nearly 500 times to his 2.9 million followers, including those who replied to lambaste “barbarian” journalists. Fundamedios, a nonprofit that promotes freedom of expression, reported that President Correa’s supporters called the journalists “mercenaries,” “rats,” “corrupt press,” and “lackeys of the empire.’”

“Government supporters then disseminated the journalists’ private information and photos, even ones where their children appear,” wrote Fundamedios.

- Ukraine’s Independent Media Council, a non-governmental body, summoned reporters after a complaint that journalists violated ethical standards by reporting that Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, set up an offshore company at the height of warfare between government and pro-Russian forces. The media council criticized how the journalists handled the story, but said the state-run television channel was ultimately justified in broadcasting the piece.

“It was a bit like a public whipping,” said Vlad Lavrov, an investigative reporter with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, which worked on the Poroshenko story. “But we said we stand by the story and that they are judging the story not on correctness of the facts, but on our editorial choices of how the story was told.”

- In Venezuela, reporter Ahiana Figueroa was sacked from one of the country’s biggest newspapers, Últimas Noticias. Figueroa was part of a multi-newspaper collaboration among different Venezuelan journalists. According to the nonprofit Press and Society Institute in Venezuela, at least seven Venezuelan news platforms attacked journalists who worked on Panama Papers.

- Keung Kwok-yuen, a senior editor at the popular Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao, was unexpectedly sacked the same day in April the newspaper published a front-page story that exposed offshore activity of a former commerce secretary, a current member of the legislature, one of the world’s richest men and Hollywood martial-arts star Jackie Chan.

- Reporters Without Borders and others condemned the move. “The handling of Mr Keung’s dismissal is full of anomalies making it difficult for anyone to accept it as a pure cost-cutting move,” the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Hong Kong said in a joint statement signed by associations and unions of journalists. Hundreds of journalists and citizens rallied outside Ming Pao’s office on 2 May, waiving sticks of ginger (“Keung” means “ginger” in Cantonese) and demanding Keung’s reinstatement.

Journalists who simply relayed reports of Panama Papers were also targeted. In China, media censors instructed websites to “self-inspect and delete all content related to the ‘Panama Papers,’” according to China Digital Times. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the communications minister warned journalists to be “very careful” about naming names from the Panama Papers, including, it was presumed, the sister of President Joseph Kabila.

“Investigative journalists are used to working under intense pressure, but in countries where press freedom isn’t the norm, these pressures can become debilitating and even dangerous roadblocks for reporters,” ICIJ Director Gerard Ryle said.

“One of the benefits of collaboration is the way journalists can band together to overcome these issues — whether it’s through sharing expertise, resources, or just helping a partner to get their story published. ICIJ has been lucky to work with such a courageous group of reporters who have made it possible to tell some important stories that might have otherwise been quashed.”

A few days after publishing his Panama Papers scoop in Niger’s L’Évènement, Moussa Aksar traveled north to a town in the Sahara Desert where he often spends time in the summer. It was a relief, Aksar said, after the media attacks and the “intense” social media posts that proliferated after his story.

Now, back at home in Niger’s capital, Niamey, Moussa says the benefits of working as part of the Panama Papers team are clear, even though authorities in his country have not announced any investigation or inquiry as a result of his newspapers’ findings.

“Publishing Panama Papers with hundreds of other journalists allowed me to be part of the big league,” he said. “The protection of the partnership with ICIJ provided me with access to important sources of information and strengthened the public’s trust in my work.”

Aksar says he has no plans to stop reporting on the Panama Papers and other subjects that make his government squirm.

Read more in Accountability

The Panama Papers

How Panama’s revolving door helps shadowy industry defy reform

In a country where top-drawer lawyers move freely between government posts and offshore law firms, bringing lasting change to Panama’s offshore industry remains a challenge

Accountability

Center among leaders in filing Freedom of Information Act suits

Seventeen trips to court since 2000; 10 won or settled

Join the conversation

Show Comments