Introduction

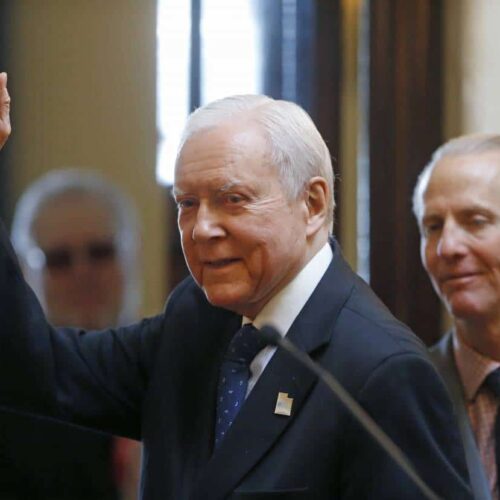

In August, a nonprofit group dedicated to archiving the official and personal papers of Sen. Orrin G. Hatch, R-Utah, gathered donors for golf at an “authentic yet refined” luxury mountain resort boasting “the largest spa in Utah.”

The fundraising event was also an opportunity to spend two days with Hatch himself — the powerful chairman of the U.S. Senate Finance Committee.

Companies and trade associations that spent much of 2017 seeking to influence landmark tax legislation, which Hatch took a leading role in shaping, were hit up for the soiree. Among them: drugmaker Merck & Co., which, like almost every other big company last year, was lobbying for favorable tax provisions. Among other contributors writing checks to the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation in four- and five-figure amounts last August: the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and Visa, Inc.

Top donors reportedly gave $100,000 or more.

By law, corporations and organizations that lobby the federal government must disclose certain charitable contributions to nonprofits, including ones such as the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation that are intimately tied to lawmakers. They also must disclose spending to “honor” lawmakers and high-level executive branch officials if the spending meets certain criteria.

But a Center for Public Integrity analysis found more than 20 companies and trade associations that have failed to disclose payments made to nonprofit groups aligned with government officials or aimed at honoring lawmakers they may want to influence. In every instance, other companies disclosed payments linked to the same events, though varying circumstances and exceptions to federal rules allow some omissions.

Nevertheless, so far, two companies and trade associations acknowledged not properly disclosing their payments and are amending their disclosures in response to inquiries from the Center for Public Integrity.

The federal disclosure laws have loopholes, and enforcement of the so-called lobbying contribution requirement is close to nonexistent.

And while it’s difficult to determine the precise reasons, organizations are not disclosing as many instances of such spending as they used to.

Lobbying forces seeking to influence public officials have indeed reported hundreds of millions of dollars in such “honorary contributions” in the decade since this disclosure law, prompted by ethics scandals in the mid-2000s, took effect.

But the number of “honorary contributions” disclosed in the reports is roughly a third of what it was a decade ago, when the disclosure requirement first kicked in, even though the number of lobbying registrants filing the reports has remained relatively constant. Only 308 filings disclosed any such honorary contributions in 2017, the lowest number since the requirement came into force.

Out of more than 600 organizations disclosing honorary contributions in 2008, the first year the requirement was in force, more than 200 never did so again.

“When there is no peril, there is no law,” said Meredith McGehee, executive director of Issue One, a nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates for government ethics and accountability.

‘You are absolutely right’— but …

Merck’s 2017 disclosures didn’t initially include, for example, a $20,000 contribution to the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation or a $5,000 gift to a scholarship fund named for Rep. Jim Clyburn, a long-serving South Carolina Democrat.

“We are amending our lobby disclosures to reflect those charitable donations as well, and our compliance department is working to add procedures to ensure that all donations in the future are noted on all applicable disclosures,” said John Cummins, a spokesman for Merck & Co.

Siemens Corp. also amended its disclosure, to show expenses associated with an event hosted at the company’s Pennsylvania Avenue offices in Washington, D.C. At the event, the nonprofit Jefferson Islands Club honored Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, a member of President Donald Trump’s Cabinet, with the Jefferson Islands Club Citizen of the Year award.

The Jefferson Islands Club is an invitation-only group that owns a private, 50-acre island in Maryland — an island boasting a clubhouse, skeet shooting range, private trails and kayaks. The retreat is meant to provide “suitable surroundings and comforts where members may assemble, discuss and promote Jeffersonian philosophies,” according to the club’s website, which also says Rep. Steny Hoyer, a Maryland Democrat, is the latest in a long line of members of Congress to serve as honorary chairman.

A Siemens Corp. executive is on the Jefferson Islands Club board, according to Brie Sachse, a Siemens spokeswoman.

“Siemens takes its public disclosure obligations seriously,” Sachse said. “Siemens generally does not sponsor events that fall into this reporting requirement. While the contribution level alone did not trigger the reporting requirement, due to the board position of our executive, the contribution should have been reported, and the report has been amended accordingly.”

In other cases, companies and trade associations said they did not disclose sponsoring events involving covered public officials because lawyers determined the circumstances fall within exceptions laid out by the House and Senate disclosure guidance.

Those decisions are sometimes complex and dependent on the amount spent compared to the total cost of the event, and it’s common for companies to make diverging decisions about whether to disclose.

In November, the Independent Women’s Forum, a nonprofit whose mission is to “improve the lives of Americans by increasing the number of women who value free markets and personal liberty,” honored Kellyanne Conway, a senior adviser to the president, as “a woman of valor” who is “truly a tremendous role model for women and girls.”

The event carried a long list of sponsors, in different tiers, including the American Chemistry Council, the Motion Picture Association of America, and the Distilled Spirits Council. The only one that included its spending in federal disclosure reports was Google.

When asked by the Center for Public Integrity, the American Beverage Association initially said it would amend its reports to disclose sponsorship of the Independent Women’s Forum gala honoring Conway.

“They looked into it and determined you are absolutely right. It did need to be disclosed,” said William Dermody, a spokesman for the American Beverage Association. Dermody said the association was internally reviewing such spending to ensure it had no additional amendments before filing the new report.

More than a week later, Dermody emailed to reverse his stance, saying the trade association’s legal team “has been looking into that further and has informed me that no disclosure is required under the law for that kind of expense in our circumstances.”

“Sorry for the confusion,” he added.

More than a dozen companies did not respond to inquiries about how they disclosed participation in various events, or declined comment regarding their disclosures, including Novartis, the American Petroleum Institute and the American Chemistry Council.

Loopholes and interpretations

The rules date back to 2007, when Congress passed the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act in response to massive lobbying scandals centered around one-time super lobbyist Jack Abramoff. The act imposed a series of new disclosure and ethics requirements on lobbyists and lawmakers.

The requirement to disclose event sponsorships and contributions to charities controlled by lawmakers drew less attention than other provisions, such as new gift rules for lawmakers and a requirement that lobbyists disclose “bundled” campaign contributions.

The new contribution filings require twice-a-year disclosure of contributions to political committees from corporate PACs, as well as contributions to inaugural committees and presidential libraries and certain types of meeting expenses.

Brett Kappel, an attorney with Akerman LLP who advises clients on disclosure, said that when the law first took effect, the clerk of the House and secretary of the Senate, who track lobbying disclosure filings and make them available to the public, initially took a broad view on what had to be disclosed.

“The regulated community pushed back on that and they narrowed it,” he said.

When working with clients to find spending that has to be disclosed, Kappel said the biggest challenge is charitable contributions in response to requests that don’t go through the normal channels, such as requests made by members of Congress directly to high-level corporate officers.

Many of the disclosure reports filed contain only political contributions, the easiest type to verify against other public documents.

A careful reading of the rules shows there are plenty of ways for companies and trade associations to honor public officials, or give to their favorite charities, without triggering disclosure requirements.

Lawyers who advise companies and trade associations on the disclosures say they spend a lot of time reviewing specific facts around the events and the exact circumstances of their clients’ participation.

“I often end up looking at a lot of invitations to determine that member of Congress participated, but in what role: Were they being honored or were they just there as a member of the honorary host committee?” said William Minor, a lawyer for DLA Piper whose practice includes advising on disclosure requirements. “Those two things are different.”

Companies can give via their own charitable foundations, something Merck’s Cummins said the company did in some instances. They can buy sponsorship packages for events honoring a lawmaker or administration official that include gala tickets or tables, featured spots on signage, and other sponsor perks but still not spend enough to be considered “paying the costs of the event,” the language that would trigger the disclosure.

A spokesman for the Motion Picture Association of America pointed to this so-called “table exception” to explain why the organization did not disclose its sponsorship of the gala honoring Conway.

It’s also fine to give money to groups closely associated with lawmakers and government officials — but that aren’t “established, financed, maintained or controlled” by them — without publicly disclosing the donation.

Take the Wyoming Congressional Awards Council, which presents young people with medals to “recognize initiative, achievement and service.” The nonprofit council hosts an annual golf tournament in the tony resort region of Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and its website lists nearly two dozen blue-chip corporations as “2017 sponsors” — UPS, Chevron and Novartis among them.

Wyoming’s three members of Congress — Sens. John Barrasso, Mike Enzi and current Rep. Liz Cheney — are included on the board as “honorary chairpersons.”

The highest-tier donor packages for the event — the $25,000 “Wallop Level” package and the $20,000 “Gold Corporate Sponsor” package — include “appropriate recognition in letters to members of Congress.”

Out of the sponsors on the website, 16 lobby the federal government and are thus required to file the disclosure reports that include honorary contributions. Only two out of those 16 organizations — the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, a trade association, and pharmaceutical company Abbvie — elected to include information about the Wyoming event on their disclosures.

Some of the companies said they had been mistakenly included in the 2017 sponsor list, and were contacting organizers to be removed. Others, including UPS and AARP, said the event didn’t have to be disclosed because members of Congress are only honorary board members.

“The Lobbying Disclosure Act Guidance is clear that ‘A non-voting board member (e.g. honorary or ex-officio) does not control an organization for these purposes,’” a spokeswoman for UPS, Kara Ross, said in an email responding to questions.

Is anyone enforcing the law?

The secretary of the Senate and the clerk of the House are responsible for referring violations to the U.S. attorney’s office in Washington, D.C., which enforces the Lobbying Disclosure Act.

The U.S. attorney’s office has pursued civil penalties against lobbying firms for failing to file the disclosure forms altogether, said Jelahn Stewart, a special counsel to the U.S. attorney.

But Stewart said she’s not aware of any complaints concerning improper or inadequate disclosure of money a lobbying group gave to a nonprofit to honor a government official.

“The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia is committed to identifying and pursuing organizations and individuals that repeatedly disregard their filing obligations under the Lobbying Disclosure Act,” Stewart said in an email. “Repeat offenders who fail to take their reporting obligations seriously will be held accountable in order to protect the public’s right to know who is seeking to influence policy on Capitol Hill.”

The Government Accountability Office, the watchdog arm of Congress, examines lobbyists’ compliance with many requirements of the Lobbying Disclosure Act annually and issues a report to Congress, but it does not audit disclosure of honorary contributions as part of that process.

“Repeat offenders who fail to take their reporting obligations seriously will be held accountable in order to protect the public’s right to know who is seeking to influence policy on Capitol Hill.”

Jelahn Stewart, a special counsel to the U.S. attorney

“We have not examined them because we don’t have any way of identifying honorary contributions that have not been reported,” said Yvonne Jones, a director in the strategic issues team at GAO.

That means most companies and trade associations are on the honor system. As Minor points out, many big companies are struggling to keep track of activities taking place across far-flung offices and sprawling corporate footprints, and aren’t always sure what to include.

“There’s certainly room for lots of judgment calls here, and when I work with companies, I make those judgment calls all the time,” he said.

McGehee said companies and trade associations may not be aware of the requirement to disclose in the first place. But if the requirement isn’t enforced, she said, the public has no way to know what goes on when lobbyists and public officials mingle at galas and on golf courses.

“If you don’t have disclosure and enforcement of disclosure, there’s no way for the public or anyone else to go in and demand a change.”

Meredith McGehee, executive director of Issue One

“I’ve always believed that disclosure was incredibly important because it’s what gives the public insight into how the system actually works. And if the practice cannot withstand the light of day and public scrutiny, than that practice should be challenged,” she said. “But if you don’t have disclosure and enforcement of disclosure, there’s no way for the public or anyone else to go in and demand a change.”

Cigarettes, drugs and booze

Hatch entered the U.S. Senate in 1977. In January, he decided to not seek re-election this year, and Mitt Romney, the Republicans’ 2012 presidential nominee, is running to replace him.

The Orrin G. Hatch Foundation was formed in 2015 with a goal of preserving the papers of its 83-year-old namesake, and creating a center named after him.

In 2016, the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation reported raising $5.9 million in tax filings with the Internal Revenue Service, per a tax filing available via CitizenAudit.org. Multiple news outlets, including Politico, reported the foundation was heavily courting K Street donors.

But 2016 disclosure filings showed only $146,000 in contributions to the foundation from trade associations and companies that report charitable contributions under the lobbying disclosure requirements — a small fraction of the money raised.

In 2017, that number went up to $315,000. The foundation’s tax return isn’t yet available for 2017, so there’s no way to determine how much it raised in total.

Donors disclosing contributions in 2017 included: the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a trade association for biotechnology companies; liquor giant Diageo North America; pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly & Co.; hotel company Hilton Worldwide; the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America; America’s Health Insurance Plans Inc.; and tobacco giant Altria, according to House and Senate disclosure filings.

All spent millions of dollars lobbying Congress on issues including tax reform. For example, the Biotechnology Innovation Organization spent about $9.4 million. The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America spent $25.4 million, putting them among the top spenders on lobbying the federal government in 2017.

The Center for Public Integrity asked several of the companies that disclosed contributing to the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation to expand on the reasons why they contributed. None did.

“I don’t have anything additional to contribute” beyond the information in the disclosure, said Holly Campbell, a spokeswoman for the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

“Our filings speak for themselves,” said Kristine Grow, a spokeswoman for America’s Health Insurance Plans.

The Center for Public Integrity also asked the Orrin G. Hatch Foundation to voluntarily reveal how much money it raised in 2017, as well as release its donor list and comment on whether it solicits contributions from organizations with business before the Senate Finance Committee.

Trent Christensen, the foundation’s executive director, did not directly address those requests. Instead, he emailed a one sentence response: “To your questions, The Orrin G. Hatch Foundation has taken appropriate steps to ensure that its activities comply with all applicable ethics requirements.”

Pratheek Rebala, Chris Zubak-Skees and Joe Yerardi contributed to this report

This article was co-published by NBC News

READ MORE:

U.S. lobbying, PR firms give human rights abusers a friendly face

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

Why the Koch brothers find higher education worth their money

The power of the Koch brothers’ money in higher ed goes far and wide, and aims for impact

Congress

Lawmakers question the wisdom of $16 billion in ‘tax extenders’ for special interests

House Ways and Means subcommittee hearing comes on heels of Center for Public Integrity investigation

Join the conversation

Show Comments