Introduction

A small video camera stashed in a row of bushes silently recorded the comings and goings of the family of a Brussels-area man with an important scientific pedigree last year, producing a detailed chronology of the family’s movements. At one point, two men came under cover of darkness to retrieve the camera, before driving away with their headlamps off, a separate surveillance camera in the area revealed later.

The Belgian police discovered the secret film on Nov. 30 while searching the Auvelais home of a man with ties to the Islamic State terror group. But they became far more alarmed when they figured out that its star was a senior researcher at a Belgian nuclear center that produces a significant portion of the world’s supply of radioisotopes.

That realization quickly got the attention of the world’s counterterrorism experts.

A diagnostic tool used by hospitals and factories around the globe, radioisotopes are also capable of causing radiation poisoning and sickness, making them a potential target for terrorists seeking to build a so-called “dirty” bomb that could contaminate the downtown area of a major city, sowing panic and causing billions of dollars in financial losses.

Belgian authorities have since speculated that the group was trying to figure out a way to collect such materials from the nuclear center, perhaps by kidnapping the man or one of his family members as the first step in building a bomb.

Many U.S. experts — including Laura Holgate, the National Security Council’s senior director for weapons of mass destruction terrorism — consider the eventual detonation by terrorists of a dirty bomb containing radiological materials to be inevitable. “I’m surprised it has not happened yet,” Holgate told a Washington symposium three years ago, because the mechanics of such a device are simple and widely-known.

“We know that it would not require a team of nuclear physicists or even a particularly sophisticated criminal network to turn raw material into a deadly weapon,” an internal Energy Department report on the threat, designated “Official Use Only,” declared in May 2013. “In many cases, a determined lone wolf or a disgruntled insider is all it might take.”

But until now, there has been no public, concrete evidence that a particular terrorist organization is aggressively pursuing the radioactive building blocks of a dirty bomb. Experts have noted that such materials are too plentiful to count precisely, but roughly estimate they are contained in more than 70,000 devices, located in at least 13,000 buildings all over the world – in many cases without special security safeguards.

“The potential for a bad outcome when you have ISIS looking at nuclear people is substantial,” said William H. Tobey, a former deputy administrator for defense nuclear nonproliferation at the National Nuclear Security Administration. Several other experts said they are particularly alarmed that the incident occurred in Belgium, which they say has a troubled record on nuclear safety issues and lacks armed guards at its nuclear facilities.

Mohamed Bakkali, who rented the home where the films were seized in a raid, was captured on Nov. 26 and has been charged with engaging in terrorist activity and murder stemming from his alleged involvement in the complex Nov. 13, 2015, siege in Paris that killed 130 people and wounded hundreds more.

Belgian regulators said they are still investigating exactly what Bakkali and his colleagues had in mind, but the options are unsettling. “We can imagine that the terrorists might want to kidnap someone or kidnap his family,” so they can force their target to turn over the radioactive innards of such a device after removing the materials surreptitiously, said Nele Scheerlinck, a spokeswoman for Belgium’s Federal Agency for Nuclear Control, the nation’s nuclear regulator.

The researcher in question, who has not been identified, was sufficiently senior to have had broad access to sensitive sites throughout the research center. Officials declined to say if he is now under police protection.

Scheerlinck added that in the view of her colleagues, whatever was being planned would have failed, because the nation’s radiological materials are under tight control. But other Western experts are not so sure, given their belief that Belgian nuclear authorities have historically been too casual about security risks.

PAGs are primarily based on an assessment of the risk of developing cancer over an exposed individual’s lifetime.

Congressional Research Service and William Rhodes III, Senior Manager, International Security Systems Group, Sandia National Laboratories, September 2010; analysis by Heather Pennington; graphics by Mona Aragon.

U.S. complaints about Belgian security practices

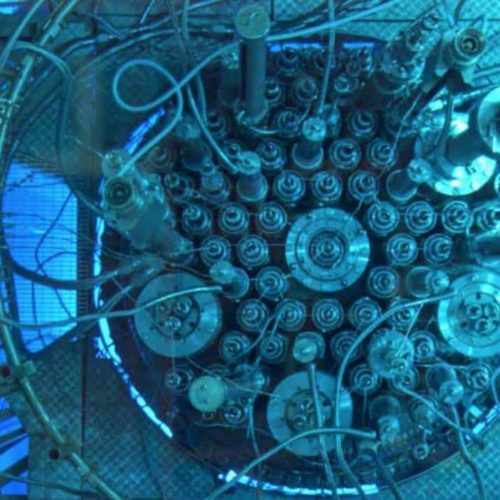

The facility where the targeted researcher works, known as the Belgian Nuclear Research Centre or SCK-CEN and located near the Bocholt-Herentals Canal 53 miles northeast of Brussels, is the site of a large nuclear research reactor, commissioned in 1961, that was tagged by the Bush administration in 2004 as having woefully inadequate security precautions.

It regularly receives U.S. shipments of highly enriched uranium – a key sparkplug of nuclear weapons – so it can make medical isotopes. But U.S. officials decided in 2004 not to send any more until security precautions at the site were significantly tightened, according to a former senior U.S. official familiar with the dispute. Washington was “concerned about the adequacy” of the Belgians’ response to a potential attack by Al Qaeda sympathizers at the research center, given that the country bars its private security guards from carrying firearms, the former official said.

These concerns were stoked in part by the conviction in 2003 of a former Belgian soccer player, Nizar Trabelsi, for plotting to set off a bomb at an air base in Kleine Brogel , 18 miles from the nuclear research center. The base is home to an estimated 10-20 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons stored near a squadron of F-16 fighters. (Trabelsi, a Tunisian citizen who admitted meeting Osama Bin Laden, was extradited from Belgium to the United States in 2013.) The facility’s security barriers were breached in 2010 by a group of peace activists, who walked around for an hour, took videos they posted on the internet, and taped anti-nuclear messages to some of the buildings.

In 2004, then-Secretary of State Colin Powell raised the reactor security issue with foreign minister Louis Michel, according to a February 2005 U.S. diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks. U.S. nuclear authorities also asked their counterparts in France — which arms guards at its own nuclear sites — to help persuade the Belgians to take the issue seriously.

Three years later, many of the security upgrades urged by Washington were still not in place, due to what Belgian officials termed “unforeseen technical, budgetary, and management issues,” according to a March 2007 U.S. cable disclosed by Wikileaks. But by late 2009, Belgian security authorities had completed some of the work and invited American officials to witness a security drill there.

In the drill, 13 armed police units from the surrounding area responded to a mock attack on the reactor site by five supposed terrorists equipped with rifles and small explosives, who pretended to be trying to gain access to dangerous radioactive materials. U.S. officials on the scene termed the exercise a sign of progress, but said room for improvement remained, and urged the Belgians to witness more robust “force-on-force” exercises conducted at similar facilities in the United States.

It wasn’t until 2013, nine years after Powell’s complaint, that Belgium enacted laws strengthening its security clearance procedures and providing serious criminal penalties for both improper handling of radioisotopes and for attempted break-ins at the high-security areas of nuclear sites. An inspection team sent to SCK-CEN and other nuclear sites by the International Atomic Energy Agency in December 2014 concluded that “the physical protection system…is robust” but also recommended additional measures to improve security.

Matt Bunn, a nuclear security expert and former White House official who is now at Harvard University, said Belgium needs to do more —much more.

“Every country, no matter how safe it thinks it is, needs to protect nuclear weapons and the materials you could use to make them against the full spectrum of plausible threats. And wherever there are potential nuclear bomb materials, they need to have armed guards,” Bunn said.

Government studies have shown that in many cases, he explained, attackers can reach sensitive areas at nuclear sites quickly, and that “it’s really hard to design systems” capable of significantly delaying a concerted assault. That’s why Britain, Canada, France, Germany and the United States have posted armed guards at sensitive nuclear sites.

Scheerlinck, the nuclear regulatory spokeswoman, responded that although the government recently decided to create a “Nuclear Quick Response Team” within the federal police, arming the guards stationed on-site at such facilities is not being considered. Doing so “would give people a false sense of security and…weapons should only be used by people who are properly trained to deal with the kind of situations that require an armed intervention (i.e. the police and military),” she said in an emailed comment.

Even after taking some of the security precautions urged by Washington, Belgium — which has seven operating nuclear reactors — was embarrassed by several 2014 incidents that suggest important gaps remain. One was the discovery in August of that year that someone had improperly opened a spigot to drain a turbine lubricant at the Doel nuclear reactor 56 miles west of the research center. The reactor seized and stalled, costing millions of dollars in immediate damages and missed revenues.

U.S. and Belgian experts have called it one of the costliest acts of nuclear sabotage ever. Investigators have not identified the saboteur, but according to Scheerlinck suspicions have fallen on workers at the plant. “That was a clear case of insider threats,” she said.

The motive remains a mystery. “[Terrorism] has not been ruled out, but has not been confirmed by the investigation either,” Eric Van der Sijpt, spokesman for the Belgian federal prosecutor’s office, said in an email.

A Belgian nuclear worker joins ISIS

Worries about insider threats at Belgian nuclear sites were further stoked in October of that year, when officials discovered that a 26-year-old Moroccan-born man who had worked in a sensitive area of the Doel power plant, Ilyass Boughalab, had died in the spring while fighting for the Islamic State in Syria.

At the time of his death, Boughalab was already under indictment in Belgium for participation in the activities of a group known as Sharia4Belgium, a now defunct radical movement bent on converting Belgium to an independent Islamic state, Van der Sijpt of the federal prosecutor’s office said.

Boughalab passed a Belgian security services background check in 2009, when he was hired by a contractor to inspect welds in highly sensitive and vulnerable areas of the reactor. Since his death in Syria, “several people have…been refused access to a nuclear facility or removed from nuclear sites because they showed signs of extremism,” Scheerlinck said.

Independent groups have reported that more radical Islamic fighters come from Belgium than from other European nations, a claim that Belgian officials dispute. “There are generally concerns about the ability of Belgian authorities to do counterterrorism stuff in a systematic, national way in coordination with other countries,” the former U.S. official said.

“Given what happened before and after the Paris attacks, you can see why” people have such concerns, he added. He was referring to the fact that a suspect in the attack was tracked to a home near Brussels two days later but not arrested due to a Belgian law restricting nighttime police operations. By the morning, the man had escaped.

While neighboring France has done much over the last decade to upgrade security for its nuclear materials, and Belgium has taken some useful steps, “you would be hard-pressed to find a comparable list of accomplishments” by the Belgians, the former official added.

Didier Vanderhasselt, a spokesman for the Belgian foreign ministry, responded that the security of “our nuclear sites is of the highest concern,” and that the country’s counterterrorism experts were “constantly monitoring the situation of all sensitive potential targets, including nuclear sites.” He also said that “as far as we know we have been implementing the same measures as the French did the last few years,” and that Belgian security precautions meet the International Atomic Energy Agency’s standards.

This story was co-published with Foreign Policy. A version of this story was also published with NBC News.

Read more in National Security

Nuclear Waste

Report: Brussels suicide bombers sought radioactive materials

Brothers caught on tape outside nuclear official’s home

National Security

Bio-threat protections inadequate

Ebola, Zika outbreaks underscore continuing threats, but reports say government response is weak, disorganized

Join the conversation

Show Comments