Introduction

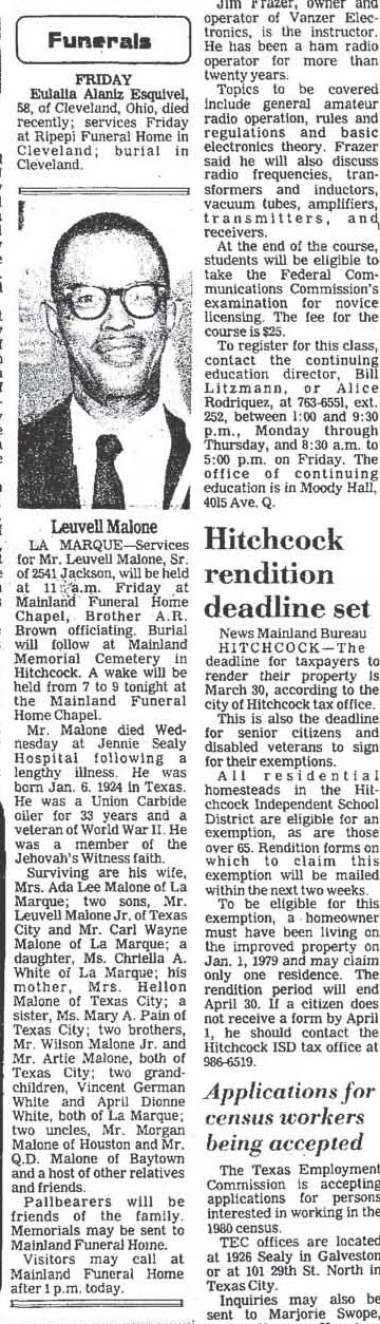

TEXAS CITY, Texas — It began with a headache; then came shaking of the hands. Leuvell Malone’s wife noticed unusual behavior. He struggled to button his shirt straight and crashed the car into the hot-water heater in the garage. Finally, a seizure landed the 55-year-old chemical worker in the hospital.

His doctor at first thought Malone might have suffered a stroke. But it turned out to be worse than that. The father of four had a rare and deadly brain tumor.

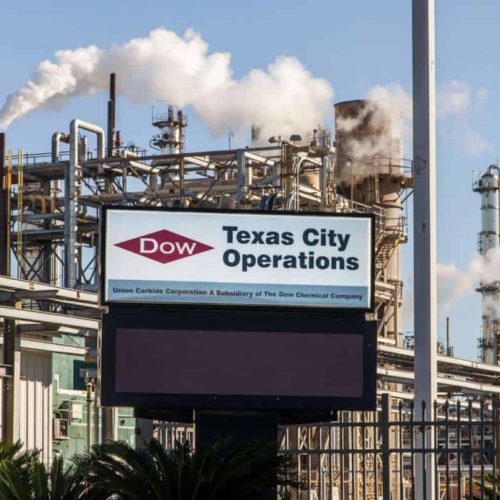

During his 32 years of greasing machines at the sprawling Union Carbide plant south of Houston, Malone feared the chemicals he breathed might one day make him sick, his sons recall. So he reported his illness to the local office of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

That was in November 1978. Just a few days later, Bobby Hinson, one of Malone’s co-workers, died of the same rare tumor, known as glioblastoma. He was 49 years old. OSHA inspectors went to the plant to find out how many other workers there had died of brain cancer.

To their surprise, the plant’s medical director already had compiled a list of 10 names. “To walk in the front door without tracing through the population and come up with 10 brain cancers is just startling,” an OSHA investigator, Dr. Victor Alexander, told a local reporter. Malone would die just three months after he was diagnosed.

More than 7,500 men had worked at the plant since it opened in 1941. Tracking those who had died was a daunting task. It took three years, but scientists at OSHA and their brethren at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH, would discover 23 brain-tumor deaths there — double the normal rate. It was the largest cluster of work-related brain tumors ever reported, and it became national news, catching the attention of The Washington Post, The New York Times and even Walter Cronkite.

The leading suspect was vinyl chloride, a chemical used to make polyvinyl chloride plastic. PVC is found in an endless array of products from plastic wrap to vinyl siding to children’s toys. Industry studies already had found higher-than-expected rates of brain cancer at vinyl chloride plants, and in 1979, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, or IARC, part of the World Health Organization, took the unequivocal position that vinyl chloride caused brain tumors.

Yet today, a generation later, the scientific literature largely exonerates vinyl chloride. A 2000 industry review of brain cancer deaths at vinyl chloride plants found that the chemical’s link to brain cancer “remains unclear.” Citing that study and others, IARC in 2008 reversed itself.

However, a Center for Public Integrity review of thousands of once-confidential documents shows that the industry study cited by IARC was flawed, if not rigged. Although that study was supposed to tally all brain cancer deaths of workers exposed to vinyl chloride, Union Carbide didn’t include Malone’s death. In fact, the company counted only one of the 23 brain-tumor deaths in Texas City.

The Center’s investigation found that because of the way industry officials designed the study, it left out workers known to have been exposed to vinyl chloride, including some who had died of brain tumors. Excluding even a few deaths caused by a rare disease can dramatically change the results of a study.

Asked hypothetically what it would mean if deaths were left out, James J. Collins, the former director of epidemiology at Dow Chemical, which merged with Union Carbide in 2001, said, “That wouldn’t make very good science.”

Richard Lemen, a former U.S. assistant surgeon general and NIOSH deputy director, put it more bluntly: “I think that borders on criminal.”

The vinyl chloride episode shows what can happen when scientific research is left to companies with a huge stake in its outcome. After launching a flurry of vinyl chloride studies in the late 1970s, OSHA and NIOSH abruptly stopped under the anti-regulatory climate instilled by the Reagan administration. The chemical industry, meanwhile, continued to update its studies and use them to defend against lawsuits by people blaming their brain cancers on vinyl chloride. The result was biased research that changed the scientific consensus. The final update of the largest vinyl chloride study is expected to be published this year.

The dominance of industry-funded research for specific chemicals has become more common as funding for biological research from the National Institutes of Health has become scarcer — declining 23 percent, adjusted for inflation, since 2003, according to the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. In contrast, industry has shown a willingness to spend lavishly on research used in litigation.

The means regulators and courts sometimes must rely on scientific research paid for by companies with a huge financial stake in its outcome.

In a brief statement to the Center, the American Chemistry Council, the trade and lobby group that paid for the industry study, noted that the IARC determination that there is no association between vinyl chloride and brain cancer “was based on inconsistent findings among the available studies, lack of an exposure-response relationship, and small numbers of reported cases in most of the studies.”

Otto Wong, the now-retired author of one of the study updates, expressed concern after hearing the Center’s findings. If industry officials knew in advance that they were excluding the deaths of workers who may have been exposed, they should have designed the study differently, Wong said.

Ongoing environmental hazard

Despite stricter regulations on vinyl chloride in the workplace since 1975, the question of its health effects remains relevant. PVC plants in places such as Calvert City, Kentucky, and Plaquemine, Louisiana, still emit vinyl chloride into the air. In 2014, companies reported releasing more than 500,000 pounds of it, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA is expected to decide this year whether to set stricter emission limits for vinyl chloride and other chemicals discharged by PVC plants.

There have also been notable cases of vinyl chloride contamination. In 2012, a train derailment in Paulsboro, New Jersey, released heavy concentrations of the chemical into Mantua Creek, sending 250 people to the emergency room and stoking fears of long-term health effects. “I’m going to be worried for the rest of my life,” said Alice Breeman, a mother of three who was caught in the release and sued Conrail, CSX Transportation and Norfolk Southern Railway. CSX and Norfolk Southern have since been dismissed as defendants.

In 2014, residents of McCullom Lake, Illinois, settled an eight-year-old lawsuit in which they claimed exposure to vinyl chloride that bled into groundwater from a nearby chemical plant, now owned by Dow, had caused a cluster of 33 brain tumors. The village has just over 1,000 residents. Dow admitted no wrongdoing in the settlement, whose terms are confidential.

Today, all legal disputes and regulatory actions on vinyl chloride must rely heavily on industry studies given the dearth of independent research. An industry-sponsored update in 2000 — the largest and most-cited vinyl chloride study — reported 36 brain cancer deaths at 37 vinyl chloride plants among workers employed from 1942 to 1972. Despite the small number of cancers, that rate was 42 percent higher than what would have been expected in the general population.

By the slimmest of margins, however, the number of deaths failed to meet a standard known as statistical significance – at least a 95-percent certainty that the high rate of brain cancer was not simply a fluke. Even one more death could have altered that conclusion.

The Center was able to scrutinize how that study was designed and conducted after obtaining nearly 200,000 internal industry documents from lawyer William Baggett Jr. He spent nine years on a lawsuit filed by Elaine Ross, whose husband, Dan, worked at a vinyl-chloride plant in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and died from brain cancer in 1990 at the age of 46. The case was settled 15 years ago for several million dollars, Baggett said, adding that the exact terms were confidential.

Vinyl chloride first gained notoriety in 1974, when it was revealed that four workers at a B.F. Goodrich plant in Louisville had died of angiosarcoma of the liver, a cancer so rare that typically no more than 25 cases per year are reported in the United States. The most recent tally of liver angiosarcomas among people exposed to vinyl chloride is 197 worldwide, including 50 in the U.S.

The evidence of carcinogenicity in the Louisville case was so overwhelming that the plastics industry couldn’t deny it. Still, the industry pushed back against new regulations, saying they could cost the nation up to 2.2 million jobs and cripple the plastics industry.

OSHA nonetheless went ahead in 1974 with a workplace limit for vinyl chloride that was 500 times stricter than the one in place when the Louisville cluster became public knowledge. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned the chemical from use in cosmetics and hair spray. Industry predictions of severe losses never came true. The regulations were met.

Built-in weaknesses

The vinyl chloride studies most often cited today — including a major study soon to be published — in fact are updates of a study first done in 1974. After companies learned of workers suffering from angiosarcoma, they quietly decided to find out what other cancers vinyl chloride might be causing.

The industry study was flawed from the start. The weaknesses built in to it only became worse as decisions were made on how to update it.

In June 1973, the industry’s trade group, then known as the Manufacturing Chemists’ Association, hired the consulting firm Tabershaw-Cooper Associates to tabulate cancers at vinyl-chloride plants. The first challenge was to compile a list of workers exposed. Rather than let scientists at Tabershaw-Cooper ultimately decide which workers should be put on the list, the chemical companies assigned the task to their own plant managers. At Union Carbide, managers decided to include only people working directly with vinyl chloride, based on some written records but also on supervisors’ distant memories.

Until the mid-1970s, exposure data was crude to non-existent. The managers reasoned that workers’ recollections of the potency of odors — categorized as high, medium or low — would be one way to estimate exposures. Jim Tarr, who worked as an air pollution regulator in Texas at the time, said such a method “doesn’t even reach the level of being junk science.”

Tarr, now an environmental consultant in Southern California, said it’s ridiculous to expect anyone to remember distinct odors years after the fact. In fact, vinyl chloride can be smelled only at levels far higher than even the old regulations allowed.

Tabershaw-Cooper’s final report — without revealing the methods used — said that measuring exposures at the plants “proved generally to be impossible.” It acknowledged that managers’ techniques for determining levels of exposure were “subjective” and had “questionable validity.”

Even with this problematic data, Tabershaw-Cooper reported in 1974 that there were more brain tumors than expected at vinyl chloride plants. A follow-up completed in 1978 reported that brain cancers at vinyl-chloride plants were occurring at twice the normal rate.

There was evidence from the start that Union Carbide workers in Texas City who died of brain cancer had been exposed to vinyl chloride. When news of the first 10 brain cancers at the plant broke in 1979, Union Carbide’s Gulf Coast medical director, Dr. David Glenn, acknowledged as much while also trying to deflect blame from the chemical.

“Although the press has strongly indicated that vinyl chloride may have been the culprit, only about one-half of our [brain cancer] cases had any known exposure to this chemical,” he said in a statement.

Yet none of those workers was included in the study updates that have formed the bedrock of today’s scientific consensus. The only brain cancer death from Texas City included in these updates was that of Luther Ott, a 57-year-old production worker who wasn’t even diagnosed until a month after the medical director’s statement. Ott died in February 1980.

Chemical industry officials knew before they hired Otto Wong to do an update that none of the 10 brain cancer deaths in Texas City had been included in previous studies, even though Glenn said half of the workers had been exposed to vinyl chloride.

One week after Glenn’s statement, Union Carbide’s corporate medical director, Dr. Mike Utidjian, told an industry task force that none of the 10 Texas City victims had a “clear cut” exposure. Nor were any included in previous studies.

Wong said it would have made more sense to start the study over rather than update a flawed one.

“From the scientific point of view, a better approach would be to do a new study,” he said.

That would entail reanalyzing which workers were exposed and which weren’t.

In fact, by March 1981, scientists at Union Carbide had determined that at least four of the workers who died of brain cancer had been exposed to vinyl chloride. The biostatistician who wrote that memo, Rob Schnatter, declined to comment for this story.

Schnatter did not keep the four dead workers a secret. He and another Union Carbide scientist acknowledged them in an article published in 1983.

Schnatter wanted to amend which workers were in the industry study. In 1982 he sent a memo to his colleagues at Union Carbide, one of whom wrote a handwritten response : “No, we are not adding people to the cohort.”

This reflected a critical decision that all but guaranteed the study’s outcome. According to the protocol, workers included in the original study could be dropped from updates if new information showed they hadn’t been exposed to vinyl chloride. But the reverse wasn’t true. Workers not initially included in the study couldn’t be added even if it turned out that they had been exposed, according to a Union Carbide memo.

In 1974, Tabershaw-Cooper was given a list of 431 exposed workers from Texas City. But when the study was updated a decade later, the number of exposed workers had dropped to 289 names.

Susan Austin, a Union Carbide epidemiologist at the time, complained in an internal memo that the odd rules for reclassifying whether workers were exposed “could lead to substantial bias.”

Collins, the former Dow epidemiologist, said it should been nearly impossible to cheat on this type of study. When scientists are deciding which workers were exposed to a chemical, they usually don’t know which ones have died. Therefore, they can’t skew the outcome by excluding dead workers.

“There’s no way to fudge the data,” Collins said.

But in this situation, Union Carbide did know which workers had died. It also knew it was excluding workers who had been exposed to vinyl chloride. The Center found no evidence that Union Carbide removed workers with brain cancer who had been in the original 1974 study. But the documents show that when the study was updated, at least three brain-cancer victims Union Carbide knew had been exposed were not included.

“It looks like they did leave them out by their own admission,” said former NIOSH official Lemen, who at one time served as a consultant for lawyer Baggett.

Kenneth Mundt, the lead author of the most recent update of the vinyl chloride study and a principal at the consulting firm Ramboll Environ, at first promised to answer questions from the Center. But weeks later, Mundt said that the study’s sponsor, the American Chemistry Council, wouldn’t allow him to talk because of pending litigation.

A Dow spokesperson said, “If Texas City workers met the eligibility criteria … then they would have been included in the industry-wide study, regardless of the cause of death …. Not all Texas City workers had opportunity for exposure to vinyl chloride.”

John Everett for the Center for Public Integrity

‘Unusual’ decisions

Documents show that more than three exposed workers might have been excluded from the updates. That’s because of a decision made in the early 1970s not to include people who were not stationed full-time in departments having direct contact with vinyl chloride. OSHA and NIOSH scientists noted that many of the brain cancer victims held jobs that would have brought them in contact with chemicals throughout the plant. They listed seven in maintenance, two in shipping and three in construction.

Leuvell Malone Sr. worked in maintenance. His son, Leuvell Malone Jr., said he had no idea Union Carbide claimed his father hadn’t been exposed to vinyl chloride.

“He was all over the plant. He did all of the oiling for all of the machinery,” Malone said. “He had to be exposed.”

The government study seems to back up Malone’s claim. NIOSH reported in its study that “maintenance men moved throughout the plant and were exposed to many different agents in an irregular manner.”

Richard Waxweiler, a former NIOSH epidemiologist involved in the investigation of the Texas City cancer cluster, said in a recent interview that he didn’t know Union Carbide had excluded so many brain-tumor deaths from the industry study. He called it “unusual” that maintenance workers like Malone were left out.

Internal Union Carbide documents show that the company didn’t dismiss the possibility that 10 other workers who died of brain cancer also may have been exposed to vinyl chloride.

In fact, exposures may have been far more widespread. In the plant’s own report to the Texas Air Control Board, which regulated air emissions at the time, Union Carbide said it released 940 tons of vinyl chloride into the air in 1975. That was after the company had implemented new pollution-control measures.

The Air Control Board calculated that in 1974, the Texas City plant released 3,000 tons of vinyl chloride — 12 times the emissions from all U.S. plants combined in 2014.

Collins said the emissions data don’t prove that everyone at the plant was exposed to vinyl chloride. But Tarr, who calculated the numbers at the time for the state of Texas, disagrees.

“There’s no question whatsoever that everyone who worked in that plant was exposed to vinyl chloride,” he said. “It was only a question of, what was the amount of that exposure and what was the duration of that exposure?”

Union Carbide strategized for nearly two years on how to limit the threat from government studies of the Texas City cancer cluster. One Union Carbide lawyer advised internally that the more brain cancer deaths there were, the easier it would be for widows like Leuvell Malone’s wife, Ada, to win lawsuits.

The company decided to do its own analysis simultaneously, reasoning that “Independent investigations of the same set of data frequently yield differing results.”

The company also decided to hold a press conference to announce its results first, telling NIOSH just two days in advance. The story was front-page news.

“Our exhaustive studies neither indicate that any deaths due to brain cancer have been caused by occupational exposure, nor do they suggest any changes to our existing employee health programs or production procedures,” plant manager Damon Engle said in a press release.

Union Carbide said only 12 employees had died of malignant brain tumors. Although earlier press reports had been higher, medical specialists at the company were quoted as saying that nine of the brain cancers “were winnowed out of the final statistical findings.”

NIOSH was blindsided by Union Carbide’s tactics. When the agency released its own findings two weeks later, media attention already had waned. NIOSH had counted 23 brain-tumor deaths, a rate that was double the national average. And it blamed the deaths on chemicals at the plant.

‘It still hurts’

The chemical industry has used its most recent studies in lawsuits to argue that vinyl chloride doesn’t cause brain tumors.

Frank and Joanne Branham grew up in the small village of McCullom Lake, Illinois, about 60 miles northwest of Chicago, and loved it there. When they got married, they built a home right on the lake. But there was one problem: the odor from a nearby chemical plant.

“There were times when we couldn’t have our windows open in the summer,” Joanne recalls. “The smell was so bad that it would hurt your eyes.”

In 1998, they moved to Arizona. Six years later, Franklin Branham started having seizures. Finally, his doctor diagnosed glioblastoma, the same rare brain cancer that had killed Leuvell Malone. Branham had only three months to live.

Joanne still breaks down talking about the day Franklin died. “It’s been 11 years, but it still hurts,” she said.

Not long after her husband’s death, Joanne visited McCullom Lake and talked to her former next-door neighbor, Bryan Freund. She discovered that Freund had the same type of cancer. Freund’s next-door neighbor, Kurt Weisenberger, had it, too.

Joanne said it was obvious to all of them that the cause was environmental.

“It doesn’t take a scientist,” she said. “That just doesn’t happen.”

They hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit claiming that a nearby plant had dumped toxic chemicals into a lagoon. They alleged that they were poisoned by vinyl chloride and other volatile chemicals.

Eventually, 33 people around McCullom Lake developed brain tumors.

Freund, one of only two brain cancer survivors from the town, has been dealing with his illness for more than a decade and said he is constantly exhausted. One year ago, he had surgery “to remove a whole bunch of my brain. They’ve taken out so much I cannot believe it,” he said.

He’s now back on chemotherapy.

The current owner of the plant, Dow Chemical, denies that people in the community were exposed to vinyl chloride, though it settled the case with the brain cancer victims about a year ago. During the litigation, the company hired expert witnesses who cited the Mundt study to prove that the brain tumors couldn’t have been caused by vinyl chloride.

One such expert, Peter Valberg of Gradient Corp., wrote that the families in McCullom Lake were citing early studies linking vinyl chloride to brain cancer but failed to cite more recent reviews.

“These in-depth summaries and updates of worker cohorts do not support a causal link between VC exposure and brain cancer,” Valberg wrote.

Aaron Freiwald, the lawyer for the McCullom Lake families, said the scientific consensus today doesn’t account for the fact that workers were excluded from industry brain cancer studies.

“We established that even one accounted-for brain cancer would completely shift the data,” Freiwald said. “If there are at least three additional cases, it seems pretty clear that the literature on vinyl chloride and brain cancer as it is has to be rewritten.”

Read more in Environment

Environment

‘It just ruined everything — the whole life’

Feeling abandoned by state regulators, hundreds of rural Pennsylvanians endure contaminated well water they blame on fracking

Environment

Hot mess: states struggle to deal with radioactive fracking waste

Potentially dangerous drilling byproducts are being dumped in landfills throughout the Marcellus Shale with few controls

Join the conversation

Show Comments