This story was co-published with NPR.

Introduction

Update, April 21, 2016: Kris Penny died on April 20, 2016. He was 40.

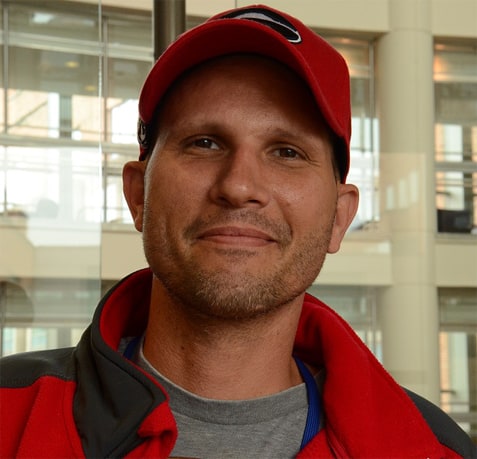

This is how Kris Penny looked in April 2015:

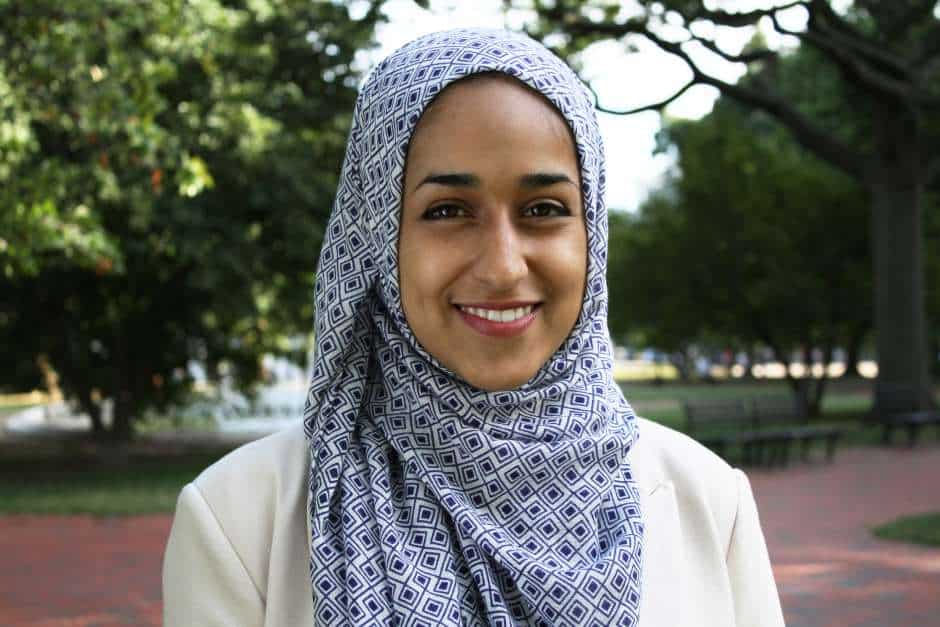

And this is how he looked six months later:

Penny is 39 years old. He lives in Clermont, Florida, and has four children. Until September 25, 2014, life was treating him well. His flooring company had just secured its first big contract.

That morning, Penny was feeling lethargic and pulled into a McDonald’s for a cup of orange juice. Seconds after he drank it he doubled over in pain. “It felt like someone stabbed me in the stomach with a machete,” he said. A co-worker drove him to the emergency room.

When he awoke in the hospital, his wife, Lori McNamara, was beside him, crying. “I go, ‘What’s the matter? I’m still here,’ ” Penny said. The surgeon who’d opened up his abdomen had found it full of cancer — type to be determined. The doctor “pretty much told me to get my affairs in order, right there on the spot.”The pathology results came in four days later. Penny learned that he had peritoneal mesothelioma — a rare cancer of the lining of the abdomen almost always tied to asbestos exposure. He concluded, after consulting with a lawyer, that he’d inhaled microscopic asbestos fibers about a decade earlier while installing fiber-optic cable underground. He sued telecommunications giant AT&T. The cable was housed in pipe made of asbestos cement. When workers maneuvered it into or out of the pipe, they generated dust. Penny says he didn’t know the dust contained asbestos, a claim AT&T disputes.

(Maryam Jameel/Center for Public Integrity)

Physicians, scientists and union officials had people like him in mind when they convened in New York in 1990 to discuss what they called the looming “third wave” of asbestos disease. The fire-resistant mineral first had killed asbestos miners, millers and manufacturing workers. Then it had taken out insulators, shipbuilders and others who worked with asbestos products. Eventually, conference attendees agreed, it would be roused from its dormant state in pipes, ceiling tiles and automobile brakes and kill again.

Environmental consultant Barry Castleman went to the New York conference. The takeaway, he said, was that “in-place asbestos was going to pose a continuing danger to millions of workers and to the general public.”

The Environmental Protection Agency has banned some, but not all, asbestos products in the United States; 400 metric tons of the mineral were consumed in 2014, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. “The consumption’s gone down by over a thousand-fold” since the 1970s, said Castleman, who testifies almost exclusively for plaintiffs in asbestos-disease cases and was retained by Penny’s lawyer. “The problem is the asbestos is still there.”

Even brief, light exposures to asbestos can breed mesothelioma, diagnosed in about 2,700 people each year in the United States. Most get it in the lining of the lung, or pleura.

What’s worse is when workers are covered in dust during asbestos-removal jobs — and possibly condemned to mesothelioma, lung cancer or the lung disease asbestosis years later — because their bosses cut corners on protections to save money.

Craig Benedict went after such people as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of New York, working in tandem with criminal investigators from the EPA. He handled more than 100 prosecutions of “rip-and-run” asbestos-abatement contractors over 15 years and put people in prison — perhaps most notably, a father and son named Raul and Alex Salvagno. After being convicted by a jury, they were sentenced to 19 ½ years and 25 years, respectively, and ordered to pay $23 million in restitution to workers for overseeing dangerously slipshod work at hundreds of locations over a 10-year period. They secretly owned a laboratory that falsified up to 75,000 asbestos sample results to convince clients the jobs had been done safely.

Benedict, who retired last year, saw victims of all stripes: Homeless people, children, immigrants and inmates. “We found asbestos in a box of lollypops a bank handed out to customers,” he said. In another case two teenage brothers were told to tear open bags of asbestos from an abatement project and “put them in a Dumpster with the regular trash. They would end up being coated head to foot with asbestos debris.” Illegal work was done at New York’s Asbestos Control Bureau and a state police barracks. It was done in a conference room used by state legislators and a supply room frequented by workers at a hospice.

Benedict said he was “never surprised” and “never jaded” by the things he witnessed. In the most egregious cases, he said, it was as if the employers “took their workers outside, lined them up against the wall and shot them with high-powered weapons. They knew — just as certainly as someone who actually did that — that their actions over time had a very high likelihood of resulting in death or serious bodily injury.”

‘I just didn’t worry about it’

Kris Penny was born in Wiesbaden, Germany, and grew up mostly on Air Force bases; both his father and stepfather were in that branch of the service. He held a series of trucking, sales and factory jobs in Ohio, Georgia and Tennessee after graduating from high school. He moved to Orlando in 2002, worked briefly for one cable-pulling firm and then moved to another, Danella Construction.

At Danella in 2003 and 2004, Penny squeezed into BellSouth manholes from Orlando to West Palm Beach. He and his co-workers would pull fiber-optic cable into asbestos-cement conduit runs, often after removing old copper-wire cable. Bursts of compressed air were used to propel string that dragged the cable between manholes. The practice kicked up dust, which at times got “pretty thick,” Penny said. “If it became too much we would jump out of the manhole.”

In his lawsuit, Penny alleges that BellSouth, now part of AT&T, never told him or other Danella workers that the conduit contained asbestos, even as it cautioned its own employees not to use compressed air or break the pipe without wetting it down. Such warnings were being delivered “by the mid-’90s at the latest, years before Kris ever got into a manhole,” said his lawyer, Jonathan Ruckdeschel.

“BellSouth claims that they stopped installing new asbestos conduit in the early ’80s, so any pipe he was working with had to have been in the ground for at least 20 years by the time he got there,” Ruckdeschel said. “And yet there’s nothing inside the manhole to tell the worker, ‘Don’t do the things that are going to cause you to get exposed. Be careful — this is asbestos-cement pipe. Invisible amounts of asbestos dust can cause you to die.’ ”

In a deposition in October, former BellSouth supervisor Jeffrey Rolfsen testified that the company relied on Danella to enforce safety rules, though BellSouth had the authority to stop the work if it had been uneasy with the contractor’s practices. “I just didn’t worry about it,” Rolfsen said. “They knew what they were doing better than I knew.”

In a written statement to the Center for Public Integrity, AT&T said, “We hire sophisticated contractors that are experienced in dealing with asbestos, and we require them to comply with [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] regulations.” The company said in a court filing that Penny “knew and understood the risks and hazards of asbestos and voluntarily exposed himself to these risks” and that his “injuries, if any, were caused by his own negligent conduct, or by the negligent conduct of others.”

Danella officials did not respond to repeated requests for comment from the Center for Public Integrity.

Jesse Davis, a safety coordinator for the Communication Workers of America, says telecommunications workers nationwide are at risk of exposures similar to Penny’s. “We’re finding more and more where asbestos-containing conduit exists,” Davis said. “Every manhole they go in, they should be asking about the presence of asbestos.” He highlighted two incidents involving CWA members.

In 2011, 31 Verizon cable workers were on a job in Fairfax, Virginia, when a passerby told them the type of conduit they were handling contained asbestos. The Virginia Occupational Safety and Health Program later cited Verizon for three serious violations of its asbestos standard, all of which the company contested. Two of the citations were dropped as part of a settlement; Verizon agreed to improve worker training. In a statement, it said it did “not believe there was any actual employee exposure to asbestos-containing materials” in Fairfax.

In 2014, a member of a Verizon crew in Lynchburg, Virginia, mindful of CWA warnings, asked a union representative to test conduit he and 19 others had been working on. The pipe’s asbestos content turned out to be 35 percent. The state issued six citations, which Verizon said it has contested. It declined to comment further.

Grim prognosis

Ruckdeschel says it’s unusual for him to represent someone as young as Penny. Most of his clients are in their 60s, 70s or 80s and were exposed to asbestos decades ago. Penny is at the low end of the latency period for mesothelioma, thought by experts to be at least 10 years.

Penny understands that his prognosis is bleak; most people with his disease survive only a year or two. He went to Baltimore in August for surgery at the University of Maryland Medical Center, hoping to extend his life. There Dr. H. Richard Alexander opened his abdomen, removed as much of the cancer as possible and hit Penny with a stiff dose of heated chemotherapy.

(Maryam Jameel/Center for Public Integrity)

McNamara, Penny’s wife, was distraught during the 8 ½-hour procedure. Her husband’s illness, she said at the hospital, “just changed our life completely. People get up, and they go to work, and they come home, and they have dinner. And they do all these things, and our life is just not like that.” She worries most about their 6-year-old daughter, Cloey, who’s close to her father and asks if he’s going to die. Penny had choked up while talking about Cloey — “my best friend in the whole world” — the night before.

Penny came through the surgery reasonably well — “a strong guy, as fit as they come,” Alexander reassured McNamara afterward — but has faltered since. He had two more operations in Baltimore, one to repair a rupture and the other so an infection could be flushed from his belly.

He went home to Florida and did not improve. There were more procedures and hospital stays. His weight dropped from 200 lbs. to about 130. In a videotaped deposition on October 27 — taken as the discovery phase of his lawsuit was winding down — he looks exhausted and skeletal. He points out his feeding tube and colostomy bag in a photograph. He speaks of being so bereft of energy that he has to “think about every step” he takes and “time everything I do.”

There will be more like him, Ruckdeschel predicts — relatively young people who get sick from even limited contact with asbestos. “And we have to just wait as the years and the decades go by.”

Read more in Inequality, Opportunity and Poverty

Unequal Risk

Some paint strippers are killing people. The EPA promised to act — but hasn’t.

For now, the only ones yanking methylene chloride paint removers off the shelves are retailers.

Join the conversation

Show Comments