The State Integrity Investigation is a comprehensive assessment of state government accountability and transparency done in partnership with Global Integrity.

Introduction

Alabamians are bracing for a sweeping political prosecution that alleges influence-peddling at the highest levels of state government. Again.

The witness list reads like pages torn from a Who’s Who in Alabama. Again.

Pundits are saying the trial will shine a light on how things actually get done in Alabama politics. Again.

Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard, whose trial on ethics charges is set to begin in March, is just the latest in a string of high-profile politicians who have faced prosecution in recent memory.

Two of Alabama’s past six governors have been convicted while in office and sent to prison, one on a bribery conviction he still is appealing and the other for appropriating inaugural campaign funds for personal use. Now a lawmaker is asking the attorney general to investigate rumors that current Gov. Robert Bentley has used state resources for personal purposes, rumors that surfaced after Bentley’s wife filed for divorce in August.

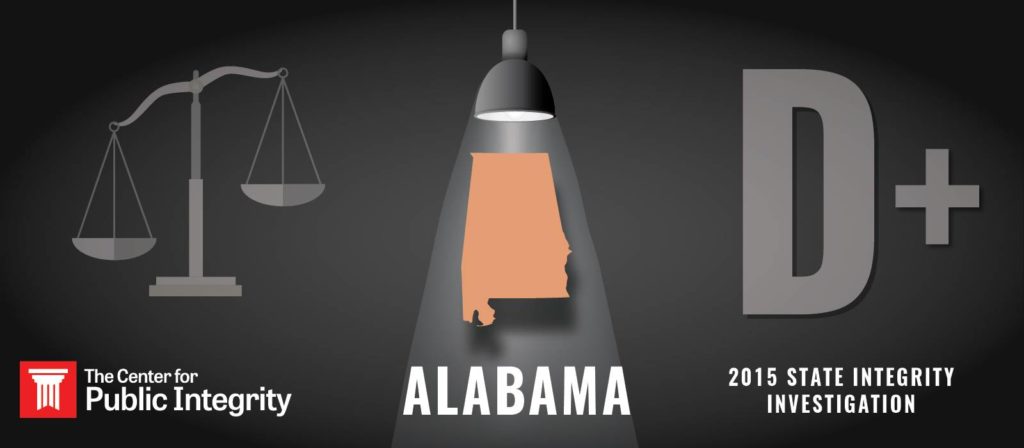

Given all of this, it’s no surprise that Alabama scored a 67, D+, on the State Integrity Investigation, an assessment of state government accountability and transparency by the Center for Public Integrity and Global Integrity. While the score places Alabama in 7th place among 50, the highest-ranking state, Alaska, received a grade of C, and 11 earned Fs.

Alabama’s overall score was somewhat lower than what it received the first time the project was published, in 2012, when it was given a C-, though its ranking that year was 17th. The two scores are not directly comparable due to changes made to improve and update the project and methodology, such as eliminating the category for redistricting, a process that generally occurs only once every 10 years.

A pattern of corruption

Governors are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the tradition of corruption in Alabama government.

In 2011, three people — a lobbyist, a casino developer and a state representative — pleaded guilty in a case that alleged legislators were bribed to vote for a bill to legalize electronic bingo. Eight other people, including four legislators, were found not guilty after a federal trial.

An investigation into corruption in the state’s two-year college system netted more than a dozen guilty pleas and convictions between 2009 and 2012, including three legislators, the college chancellor and other state officials.

And the list goes on.

For many years, Alabama’s ethics law was criticized as toothless. But in 2010, the law was revised to give the Ethics Commission subpoena powers and to formalize the investigative process, and in 2011, the commission was given a guaranteed budget.

The 2010 law together with subsequent reforms also made it illegal for public officials and employees to accept most gifts valued at $25 or more. After that law was passed, the commission began a training program to make sure officials and employees knew details of the ethics laws.

John Carroll, former acting director of the commission and a longtime political observer, said that since then, minor or unintentional violations have been drastically reduced. But the state still is plagued by allegations that the laws are broken on a much bigger scale.

Ironically, after championing the 2010 changes, Hubbard, the former speaker, is now challenging their constitutionality. His attorney has questioned parts of the law and how prosecutors are applying it in the case, including whether the statute covers political party activity.

Hubbard, one of the most powerful political players in the state, was indicted as part of an investigation by the attorney general’s office into corruption at the Statehouse and is awaiting trial on 23 felony ethics charges. He pleaded not guilty. Most of the charges allege that Hubbard used or attempted to use his legislative office to benefit clients of one of his private companies or used his position when he was chairman of the state Republican Party to secure business for his private companies. He also faces four charges that he lobbied the governor’s office and the Department of Commerce under the auspices of his private business for two clients.

The attorney general’s probe has already netted one legislator, who has pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor count of using his office for personal gain and agreed to cooperate with the ongoing investigation. Another legislator was charged with perjury in relation to the investigation but found not guilty.

Alabama actually scored relatively well in the two categories of legislative and executive accountability, earning a C and a B-, respectively.

But the state’s scores were pulled down significantly by two categories for which it was given Fs — political financing and access to information.

Political financing

The sky’s the limit for political donations in Alabama; there are no caps on contributions from individuals, businesses or political action committees. The state had capped contributions from corporations, but it lifted that cap beginning in 2013.

The only significant restriction the state places on political financing is a ban on PAC-to-PAC transfers, which when approved in 2010 ended what had become an extensive shell game of moving money through multiple PACs so its source was obscured by the time it reached the candidate.

People and corporations can still deflect attention from their donations by giving to multiple PACs, however. While some states have adopted rules that require a PAC’s name to reflect its true purpose, Alabama has not. The state has a plethora of “good government” PACs, which tell voters nothing about the committees’ funding or goals.

The state does have strong campaign finance disclosure requirements. However, until this year, no one was charged with monitoring contribution reports and investigating suspected wrongdoing. That changed in September 2015. A new law gives the Alabama Ethics Commission the authority to investigate alleged violations of the Fair Campaign Practices Act, with the aid of the secretary of state’s office. If the commission determines there is reason to believe the act has been violated, it may forward the information to the attorney general or a district attorney for prosecution.

Access to information

Alabama law does give citizens broad rights to access public records, with some exceptions. Generally, the public doesn’t have much difficulty getting routine state records, many of which are posted online.

But when requesters do have trouble, there is no central office for them to call and no appeals process set out in law except for filing a lawsuit in circuit court, a step that can be expensive and time consuming. Otherwise the only option is for the public or media to try to publicly shame officials into releasing records.

It took more than 15 months of such shaming and an attorney general’s opinion before the Hoover City Schools released payroll records requested by the Alabama School Connection, an online education news site.

Alabama Press Association general counsel Dennis Bailey said the lack of an appeals process is a huge hole in the open records law. But the press hasn’t pushed to fix that problem in recent years, frankly because it’s afraid what legislators might do if a bill to revise the law were introduced.

“The way it works in practice is that most of the time we end up getting information pretty quick and free,” Bailey said. “We don’t want to mess that up.”

Join the conversation

Show Comments