Introduction

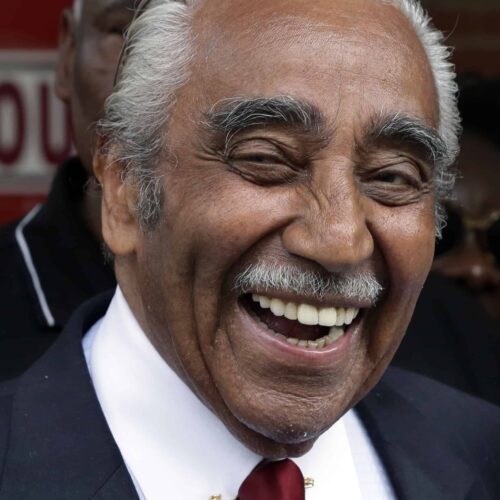

Rep. Charlie Rangel, D-N.Y., sure sounds like a man running for re-election.

“Contribute now to support Congressman Rangel’s fight for a deal benefiting everyday Americans!” reads a May 13 fundraising appeal from Rangel’s campaign committee to supporters, referencing a trade deal known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Click the words and a Rangel for Congress donation page pops up.

“Pitch in today to help me enact laws that open trade with Cuba,” another Rangel fundraising message sent May 10 states.

And after President Barack Obama’s State of the Union address in January, Rangel wrote his backers about standing with Obama “against Republican obstruction and opposition.”

Another come-on linking to a donation page follows: “Will you contribute to the fight for middle class economics?”

But these and other recent Rangel campaign solicitations are misleading, at best, because there is no Rangel campaign.

Rangel is retiring after his current term expires.

So whatever cash Rangel’s campaign committee raises this year won’t likely promote the 23-term congressman’s legislative agenda, or stymie conservatives, or surreptitiously angle him toward one more Election Day hurrah.

Instead, the money will fill Rangel’s own pockets.

The situation dates to June 23, when Rangel personally loaned his namesake committee $100,000 — immediately before defeating state Sen. Adriano Espaillat in a tight Democratic primary.

Rangel, who easily won re-election in November against token competition, now wants his cash back.

But there’s a problem: Rangel’s committee is effectively broke — it reported less than $4,500 to its name through March, according to federal records — and must raise cash to pay the congressman back.

“The congressman — he does not want to have any misinterpretation: this is for debt reduction, and he’s not running in 2016,” Rangel for Congress fundraiser Darren Rigger said of the committee’s fundraising efforts of late.

But the mere existence of such campaign solicitations is confusing. Indeed, it isn’t terribly transparent of Rangel, or any political candidate, to suggest they’re raising campaign money for one reason when they’re really raising it for another, said Daniel I. Weiner, at New York University School of Law’s Brennen Center for Justice, which advocates for campaign reform.

“There’s no truth-in-advertising provision in federal election law, though,” Weiner said.

Such financial drama is itself stunning given that Rangel not long ago ranked among Democrats’ most notable fundraisers.

Beyond filling his own coffers with ease, he spread hundreds of thousands of dollars last decade to charities and fellow Democrats via his campaign committee.

But when the U.S. House in 2010 censured Rangel for ethics and campaign finance misdeeds, his fortunes — both political and financial — waned. Rangel has maintained he did not do “anything corrupt,” although a federal appeals court this month rejected his attempt to overturn the censure.

Rangel’s quest to clear his campaign debts, including recouping the money he loaned his campaign, won’t be easy, and so far, few Rangel supporters or congressional colleagues are keen on helping him.

From Jan. 1 to March 31, Rangel for Congress raised just $9,155, according to federal records. Eleven individuals and one political action committee — Promise PAC, led by Rep. Marcia Fudge, D-Ohio — contributed an amount ranging from $250 to $2,000.

The campaign immediately spent most of this money, about $8,500, during the year’s first three months. The majority went to the New York City Department of Finance to pay an “administrative levy” bill, the campaign’s latest disclosure shows.

In addition to direct solicitations, Rangel’s campaign did conduct a fundraising event on April 20 in Harlem, where the minimum suggested contribution was $125.

An advertisement for the event said money raised would go to “support Charlie and his efforts.” But unlike many other Rangel campaign fundraising pitches of late, the message noted — with a preceding asterisk — that “Congressman Rangel is raising money to retire campaign debt.”

Rangel for Congress won’t have to report until July how much money it raised from the affair.

Another wrinkle in Rangel’s quest to get his hundred grand: Since Rangel says he’s not again running for Congress, his campaign committee must operate under federal campaign finance rules governing the 2014 election cycle.

That means someone who didn’t donate to Rangel last cycle could conceivably give up to $5,200 — $2,600 toward both Rangel’s primary and general election — to help the Rangel campaign pay back its candidate, said Paul S. Ryan, senior counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan election reform outfit.

But people who already donated the maximum to Rangel during his 2014 elections would be barred from helping Rangel’s campaign retire the loan.

And it’s not just Rangel himself who is technically owed money by the Rangel campaign.

The Rangel for Congress committee also owes nearly $36,000 to New York City-based consulting firm “RGS Group Inc.” for fundraising work it appeared to do during the 1990s.

Rangel’s campaign may, however, have outlived its creditor: New York state business records indicate RGS Group Inc., which formed in 1994, ceased operations in 2003.

The man listed in New York state business filings as the group’s contact, lawyer Richard Stelnik, said Monday that he “knows absolutely nothing” about RGS Group Inc. and that he’s “never had any interactions with Charlie Rangel.”

There’s also an RGS Group. Inc. registered in Delaware. It formed in 1995 and folded in 1999, according to state business records. It’s unclear if the two RGS Group Inc. entities are related.

Rigger, Rangel’s fundraiser, said no RGS Group Inc. official has attempted to collect on the debt Rangel’s committee reportedly owes it.

At minimum, Rigger says he’s “confident” the Rangel campaign will pay off its debt to Rangel, the man, by 2016.

So why would anyone donate to a lame-duck politician attempting to avoid eating a cool $100,000?

Kenneth Bialkin, a partner at law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom partner, said his $250 donation to Rangel on March 31 stems from the 84-year-old congressman changing his mind and attending a highly controversial speech to Congress by Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu.

Rangel did a “statesman-like thing,” Bialkin said.

Robert B. Blancato, president of Washington, D.C.-based government relations firm Matz, Blancato & Associates, also gave Rangel’s campaign $250, on March 30.

The reason, Blancato said, is simple: he’s known Rangel for about 40 years and considers him a close friend.

“He was a valued mentor to me,” Blancato said, “and when his people reach out, I’ll help how I can,”

Regardless of whether he gets his money back — Rangel could choose to simply forgive his campaign’s debt to him — the congressman need not worry about becoming a pauper in the twilight of his political career. .

Rangel, while not slam-dunk rich by congressional standards, is wealthier than average among his congressional colleagues. His estimated net worth in 2013 about $1.74 million, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

And although Rangel is known for his unabashedly liberal brand of politics, his most valuable assets were conservative: cash holdings, a mutual fund, a bond fund and a life insurance policy.

Read more in Money and Democracy

Money and Democracy

Financial facts about Rick Santorum (4)

Money and Democracy

Meet the ‘dark money’ phantom

Ohio lawyer at the nexus of nonprofit network is conservatives’ secret weapon

Join the conversation

Show Comments