Introduction

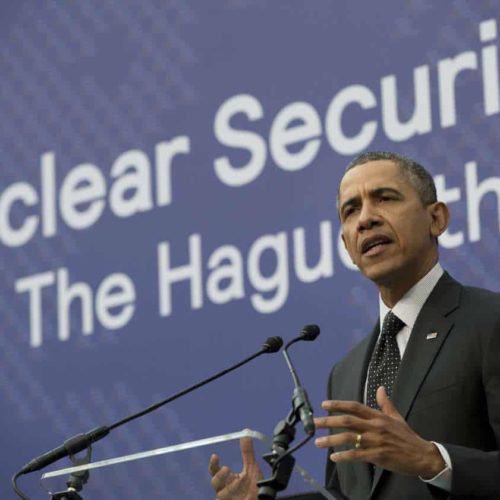

Since the start of his presidency, Barack Obama has been clear that one of his major goals was to secure nuclear weapons and materials, and as recently as March, at the Nuclear Security Summit in Holland, the president declared that “it is important for us not to relax but rather accelerate our efforts over the next two years.”

Instead, to little notice, the administration has decided to spend money at an even greater rate than before to refurbish and modernize nuclear weapons while slashing the amount it is spending to prevent terrorists from making or getting their own.

According to a new analysis of nuclear security spending by a bipartisan group at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the administration in its proposed 2015 budget chose to cut nuclear nonproliferation programs in the Energy Department by $399 million while increasing spending on nuclear weapons by $534 million.

In addition, despite missing a self-imposed deadline of April 2013 for ensuring that nuclear materials were safe from terrorists across the globe, the White House at about the same time rejected a confidential Energy Department-sponsored plan to accelerate those efforts by 2016, the year Obama is slated to convene a fourth international summit on the issue.

The proposal, which appears in a May 2013 report obtained recently by the Center for Public Integrity, was intended to address the huge amount of unfinished work in the Obama administration’s nonproliferation plan.It said that more than two tons of portable, easily-weaponized uranium were still being held in scores of nuclear research reactors, while the world’s supply of another nuclear explosive, plutonium, was growing at a rate of about 740 bombs’ worth a year.

Despite progress, there remained enough nuclear explosive material in the hands of civilians to cobble together 40,000 atomic bombs.

The 12-page May 2013 report called for an acceleration of efforts to lock down or eliminate more of these dangerous materials — as well as radioactive isotopes that could be used in bombs that could contaminate large urban areas. But the White House, after an interagency struggle that climaxed at a Cabinet-level meeting in January, produced a 2015 budget proposal that slighted many of the report’s key recommendations and reduced spending on nonproliferation programs. It did so, officials and experts say, to ensure the government could devote more funds to refurbishing and modernizing the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

“As they were putting the administration’s budget together, there were debates,” said Matthew Bunn, a former White House official and professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “Should they provide more money for nonproliferation, or more money for weapons? It’s clear that weapons won that debate.”

Laura Holgate, the White House senior director for weapons-of-mass-destruction terrorism, did not dispute the budget analysis, but said the reductions in nonproliferation spending reflected the achievement of many of President Obama’s goals.

“The President’s nonproliferation and nuclear security priorities were protected,” she wrote in an email. “The decreased budget reflects natural and predictable declines based on project completion. The U.S. commitment and capacity to support global nuclear security activities remains strong and unparalleled.”

The report describing urgent unfinished business in nuclear security was prepared by the staff of the Global Threat Reduction Initiative, part of the National Nuclear Security Administration, a semi-independent arm of the Energy Department. The NNSA also oversees the production of nuclear warheads, so internal budget skirmishes between those who favor nonproliferation and those who seek more spending on the nuclear arsenal are frequent.

For the current year, fiscal 2014, Congress authorized $1.95 billion in spending by the NNSA on nonproliferation programs. The White House budget for 2015 proposes $1.56 billion — a 20 percent reduction.

In fiscal 2010, NNSA spending on nuclear weapons was about three times as high as for nonproliferation. Under the proposed White House budget, weapons spending would outstrip nonproliferation spending by over five-to-one.

The NNSA report said that because of the administration’s four-year effort, “the world today is unquestionably more secure from the threat of nuclear terrorism than it was four years ago.” But the report added that there were “still serious threats that require urgent attention.”

“Experts continue to believe that terrorists are seeking a nuclear or radiological weapon — either by making one or stealing one,” the NNSA report says. “A handful of highly enriched uranium (HEU) or plutonium the size of a grapefruit is all that is needed to make a nuclear bomb with the potential to kill hundreds of thousands of people. A small capsule of cesium the size of a pencil is enough for a radiological ‘dirty bomb’ that could contaminate an entire city and result in billions of dollars in economic devastation.”

To blunt these threats, the NNSA report — marked “For Official Use Only” — sought to set the following ambitious, new goals, to be achieved by December 2016:

-

It called for removing or eliminating 1.1 metric tons of weapons-grade uranium and 400 kilograms — over 880 pounds — of plutonium from sites around the world.

-

It urged the removal of all highly-enriched uranium — that is, uranium that could be fashioned into a bomb — in eight more foreign countries by the same date.

-

It proposed that the administration make a better accounting of existing plutonium stocks, decide the best ways to dispose of it, and persuade other countries to balance production with consumption so that the net global stockpile will finally begin to shrink. This would be a major accomplishment, since the world’s total accumulation has instead been rising steadily, by 100 metric tons since 1998.

-

It proposed accelerating U.S. efforts to convert research reactors that use weapons-grade uranium to burn a form of uranium that cannot easily be used to fuel weapons — calling for 13 more such reactor conversions by the end of 2016.

None of these proposals was adopted.

Postponing goals

“Despite President Obama’s well-deserved reputation as an advocate for nuclear security, the Obama administration has been cutting nuclear security programs year after year for most of its term in office,” wrote Bunn, a former Clinton White House official; William Tobey, deputy administrator for the NNSA’s Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation office during the Bush administration; and Harvard researcher Nickolas Roth, in their own, 32-page report.

Besides flagging these reductions, the Harvard report’s authors said they anticipate reduced spending on nonproliferation programs in the State and Defense departments, a conclusion based on congressional reports and briefing notes, discussions with agency officials, and internal documents, including a copy the NNSA report — which the Center obtained separately.

The 2015 budget proposal would leave enough money to upgrade security for just 105 buildings where dirty bomb materials are stored — 53 in the United States and 52 abroad — by September 2015, the end of the fiscal year, according to the Harvard study’s analysis.

That would leave about 12,800 buildings worldwide in need of such upgrades, and delay completion of the work from 2025 to at least 2044.

The proposed 2015 budget would also cut $40 million from the reactor conversion program, instead of boosting its funding as the program managers sought. As a result, the Harvard study says, the conversion program would not be wrapped up until 2035, instead of 2020. “That is 15 more years that weapons-usable nuclear material will continue to be used — often in inadequately protected facilities,” it stated.

The 2015 budget provides enough funds only to eliminate or secure about 1,540 pounds of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium abroad by 2016, about half the goal that the program managers sought.

While the NNSA proposal called for securing radiological materials at 450 foreign and domestic sites by the end of 2016 that could be used to make a so-called dirty bomb, a conventional explosive device designed to spread dangerous radioactive material over a wide area, the budget provided funds for only 410 such sites. While that gap may seem small, the proposal noted that just a tiny amount of one such isotope — cesium chloride, widely used to sterilize blood — could wreak havoc in a major city.

Budget documents submitted to Congress by the administration also contain no mention of the proposed goals of removing weapons-grade uranium from eight additional countries, eliminating plutonium on three continents, and halting the net growth of foreign civilian stocks of plutonium, according to Bunn.

Bunn said some administration officials concluded that the more ambitious agenda was impractical, because countries with remaining stocks of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium have resisted giving up those materials. But he said the government will have a hard time locating needed funds if those countries’ policies shift.

The cuts followed a bruising debate within the administration over a bid by newly-appointed Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz to get an extra billion dollars from the Office of Management and Budget so he could expand both nuclear weapons and nonproliferation spending at the same time. The extra funds would have had to come from the Pentagon’s allotment, in a budget transfer.

But the Defense Department opposed the idea, having provided $4.5 billion to DOE over the past four years to keep the weapons programs moving along, albeit at a slower pace than the Pentagon wanted.

And so, during a Cabinet-level meeting to resolve the dispute in January, a former White House official said, Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall, nonproliferation coordinator on the National Security Council, agreed with Sylvia Burwell, director of the Office of Management and Budget, that nonproliferation spending would be reduced while weapons programs were protected. Sherwood-Randall was subsequently nominated by Obama to be the deputy energy secretary.

The former official, who spoke on condition he not be named in order to characterize the internal deliberations, said that there was a consensus that the administration’s four-year nuclear security effort had already accomplished the easier, high-payoff projects. “They had basically achieved their goals,” said the official. “The stuff that was left was the stuff that was hard to do.”

When asked at the Aspen Institute’s security forum July 25 why President Obama’s 2009 goal of securing all vulnerable nuclear materials in four years had not been met, Laura Holgate said the White House effort had aimed to “make a big dent” in the world’s civilian stockpiles of nuclear materials.

“I don’t think … we can say it was not met,” she said. “What he was talking about is a global effort over that four-year time, like a sprint in the middle of a marathon. Nuclear security is perpetual. As long as you have materials, you have to have security. The point of the speech was to say let’s work as hard as we can, over the next four years, to make a big dent in the amount of material that is vulnerable. And we’ve succeeded.”

“In that time 12 countries eliminated all fissile material on their territories that could be used in a weapon, including Ukraine,” she said. “Think how differently we would be thinking about the Ukraine situation now if the 50 kilograms of highly-enriched uranium — that’s a couple of bombs worth — were still at that Kharkiv Institute, which the rebels have taken over. That’s a very different situation than what we would have today.”

Derrick Robinson, deputy press spokesman for the NNSA, added that some of the ideas in the internal proposal that were not funded might still be put into “out-year budget projections.” He also said they may wind up being “funded by countries other than the United States or through international organizations,” such as the International Atomic Energy Agency, a UN group.

A popular policy among Republicans

According to a study by the Center for Nonproliferation Studies, the Obama administration will spend at least $179 billion from 2010 through 2018 to maintain the United States’ nuclear stockpile.

Because of plans to replace the “triad” of land-based missiles, nuclear-armed subs and nuclear bombers, the Center reported last September, the costs are expected to grow to $500 billion over the next 20 years.

Those costs include billions to repair, replace and modernize components to extend the shelf life of many of the the roughly 7,400 warheads and bombs in the nation’s aging nuclear arsenal. Sen. Jeff Sessions, an Alabama Republican, at a March 5 Senate Strategic Forces Subcommittee hearing, called the White House’s proposed nuclear weapons budget “pretty close to where we need to go … It seems like we have had a move that recognizes the triad’s importance and the need to modernize nuclear weapons.” In the same hearing, he later tempered his praise with criticism of what he said were delays in the modernization effort.

As the program was getting underway in 2010, Vice President Joseph Biden defended it by saying it was part of the path toward the administration’s goal of a nuclear weapons-free future.

“This investment is not only consistent with our nonproliferation agenda; it is essential to it,” Biden said in a speech at National Defense University in Washington. “Guaranteeing our stockpile, coupled with broader research and development efforts, allows us to pursue deep nuclear reductions without compromising our security. As our conventional capabilities improve, we will continue to reduce our reliance on nuclear weapons.”

The White House’s decision to favor new bomb-building over nonproliferation angered arms control advocates and some Democratic lawmakers, but was welcomed by Republicans, who have found themselves in close agreement with Obama’s White House and Defense Department appointees.

“The administration is actually [the] first to come to our assistance in fighting back reductions” to nuclear weapons-related spending, a Republican congressional staff member commented.

Critics of the administration say its budgeting reflects excessive zeal to implement Obama’s pledge, made during Senate debate over ratification of a 2010 nuclear arms treaty with Russia, that he would spend many billions of dollars to refurbish and modernize the nuclear weapons that remained after agreed reductions.

At a Senate Energy and Water appropriations subcommittee hearing April 9, Sen. Diane Feinstein, D-Calif., pressed Moniz on the issue of reducing nonproliferation spending. “What I see are additional cuts to well-managed programs that have made this country safer from nuclear terrorism, at the expense of increased funding for poorly-managed nuclear weapons programs,” she said.

Moniz responded that the administration had made a commitment to “sustain the fundamental [nuclear weapons] stockpile posture,” and that “regrettably — and I say that quite honestly, quite regrettably — within our relatively small part of the [defense] budget we must support weapons, nonproliferation, naval reactors, environmental cleanup and intelligence programs.”

Tobey, one of the Harvard study authors, said he was “perplexed” by the administration’s decision to cut the proliferation budget.

“If you listened to the president’s rhetoric at the nuclear security summit in the Netherlands [in March], he talks about stepping up our game and not coasting to the finish” of his administration’s nonproliferation drive, Tobey said.

Daryl Kimball, executive director of the Arms Control Association, said, “There is a mismatch between the administration’s budget request and their statements about the urgent need to accelerate efforts to work globally to secure weapons-usable nuclear materials. We think this mismatch needs to be corrected. The administration needs to put its money where its mouth is.”

Read more in National Security

National Security

Russian gas company hires D.C. lobbyists

Major shareholder is part of Putin’s ‘inner circle’

National Security

Nuclear weapons lab employee fired after publishing scathing critique of the arms race

Los Alamos lets a 17-year employee go after retroactively classifying his published article

Join the conversation

Show Comments