Introduction

In the name of job creation and clean energy, the Obama administration has doled out billions of dollars in stimulus money to some of the nation’s biggest polluters and granted them sweeping exemptions from the most basic form of environmental oversight, a Center for Public Integrity investigation has found.

The administration has awarded more than 179,000 “categorical exclusions” to stimulus projects funded by federal agencies, freeing those projects from review under the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA. Coal-burning utilities like Westar Energy and Duke Energy, chemical manufacturer DuPont, and ethanol maker Didion Milling are among the firms with histories of serious environmental violations that have won blanket NEPA exemptions.

Even a project at BP’s maligned refinery in Texas City, Tex. — owner of the oil industry’s worst safety record and site of a deadly 2005 explosion, as well as a benzene leak earlier this year — secured a waiver for the preliminary phase of a carbon capture and sequestration experiment involving two companies with past compliance problems. The primary firm has since dropped out of the project before it could advance to the second phase.

Agency officials who granted the exemptions told the Center that they do not have time in most cases to review the environmental compliance records of stimulus recipients, and do not believe past violations should affect polluters’ chances of winning stimulus money or the NEPA exclusions.

The so-called “stimulus” funding came from the $787-billion legislation officially known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, passed in February 2009.

Documents obtained by the Center show the administration has devised a speedy review process that relies on voluntary disclosures by companies to determine whether stimulus projects pose environmental harm. Corporate polluters often omitted mention of health, safety, and environmental violations from their applications. In fact, administration officials told the Center they chose to ignore companies’ environmental compliance records in making grant decisions and issuing NEPA exemptions, saying they considered such information irrelevant.

Some polluters reported their stimulus projects might cause “unknown environmental risks” or could “adversely affect” sensitive resources, the documents show. Others acknowledged they would produce hazardous air pollutants or toxic metals. Still others won stimulus money just weeks after settling major pollution cases. Yet nearly all got exemptions from full environmental analyses, the documents show.

This approach to stimulus projects has left the Obama administration at odds with its usual allies in the green movement. Some environmental advocates told the Center the goals of creating a clean energy economy and more jobs don’t outweigh the risks of giving money to and foregoing supervision of repeat violators of anti-pollution laws.

“Why bring somebody who was a known bad actor and give them government money and a categorical exclusion for their project?” asked David Pettit, a Natural Resources Defense Council lawyer who has litigated cases under NEPA.

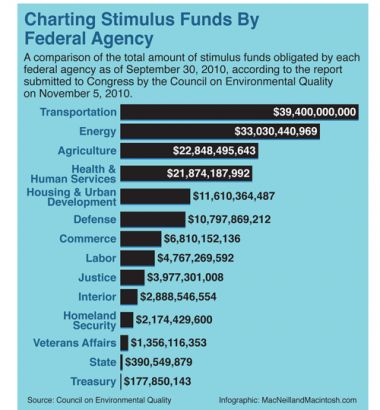

Top-level administration officials and career employees who granted the so-called categorical exclusions under NEPA defend their decisions. They argue that these exemptions were essential to accelerate more than $30 billion in stimulus-funded clean energy projects, allocated by the Energy Department, which they say have already created 35,000 jobs. They note that the department frequently grants NEPA exemptions to projects of all kinds. And in the long run, they say, the exempted stimulus activities will serve to boost energy efficiency and curb pollution.

“What we are doing is providing federal funding to increase energy efficiency and increase the use of clean energy,” said Scott Blake Harris, the Energy Department’s general counsel, who has ultimate responsibility for its NEPA decisions. “I think that sends a good message to the entire American public, whether or not there are companies that have decided to do environmentally good things after doing bad things.”

Passed by Congress in 1969, NEPA provides one of the few proactive protections in an environmental enforcement system that typically relies on penalties after harm has afflicted the environment and human health. The federal law requires companies to study possible benefits and threats to the landscape, wildlife, or human health before proceeding with a major federal project, giving officials one last chance to intervene if the work imposes a “significant impact.” Ultimately, NEPA is meant to ensure environmental factors weigh as much as economic ones.

Industry groups and their legislative allies on Capitol Hill have long complained that NEPA compliance can delay projects by months and even years, tying up companies with public notices and scientific studies costing millions of dollars. Those concerns influenced the administration’s decision to grant NEPA exemptions to streamline the environmental review process for “shovel-ready” stimulus projects that could create jobs quickly in a recession and yield “green energy” benefits down the road, according to interviews with key players.

The decision stands in sharp contrast to the administration’s recent effort to shore up the NEPA process for offshore drilling projects in the wake of the Gulf of Mexico oil spill. The Interior Department has stopped issuing categorical exclusions for drilling projects and instead is requiring more extensive environmental reviews, after a White House report revealed BP had secured a NEPA waiver for its ill-fated Deepwater Horizon rig based on outdated information.

The Energy Department — which has granted stimulus money to oil firms, chemical companies, and coal-burning utilities — has handed out similar waivers to recipients with some of the nation’s worst environmental compliance records. Among them:

- an electrical grid upgrade project in Kansas led by Westar Energy, the state’s largest coal-burning utility, which settled a major air pollution case by paying a half billion dollars in penalties and remediation costs. The Energy Department granted the NEPA waiver to Westar’s project, funded by a $19 million stimulus grant approved on the same day the settlement became official.

- a wind farm project in Texas, as well as an electrical grid upgrade project in five additional states, undertaken by Duke Energy of Charlotte, N.C. The department granted the NEPA waiver to both Duke projects, funded by a combined $226 million in stimulus grants, even as the energy corporation continues its decade-long defense against two of the biggest air-pollution cases in the nation’s history.

- a project to create clean-burning biofuel from seaweed led by the chemical giant DuPont, which faces two class-action lawsuits over water contamination caused by its toxic chemical known as C8. The department awarded DuPont’s biofuel project $8.9 million in stimulus funds in February, an amount nearly equal to the record environmental fine the company paid in 2005 to settle allegations that it hid the dangers of C8 from federal regulators for two decades.

In all, the Center has found roughly three dozen companies with past environmental problems that won NEPA exemptions for stimulus-funded projects from the Energy Department. Those projects total $2 billion — or 6 percent of the department’s total money awarded so far.

“It’s outrageous to give these companies these big breaks when they haven’t earned a bit of trust from the communities around them,” said Joe Kiger, a Parkersburg, W.Va., school teacher suffering from liver disease. Kiger filed a 2001 class-action lawsuit alleging he and thousands of citizens were being poisoned by DuPont’s C8 in their drinking water. His suit ended in a multimillion-dollar cleanup effort and a medical study funded by the company for area residents devastated by cancer and other ailments.

“I’m all for the stimulus, and I’m all for job creation,” he added, “but not at the expense of the environment and human health.”

Question of Whether Ends Justify Means

The case of a Wisconsin ethanol plant with a long history of pollution problems demonstrates how little emphasis the administration placed on environmental compliance in regard to the stimulus.

Documents obtained by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, which collaborated with the Center on this article, show ethanol producer Didion Milling received $5.6 million in stimulus money for an energy-efficiency project just weeks after a federal court ruled the company had repeatedly violated the federal Clean Water Act. Didion landed the NEPA exemption in March for expanding its plant in ways that, the documents state, “conserve energy.”

State and federal officials concede the Energy Department’s screening process relies on a boilerplate environmental questionnaire in which companies are trusted to provide relevant information about their activities, including which ones might qualify for a NEPA exemption.

Facing increasing pressure to speed delivery of stimulus money to a sluggish economy, Energy Secretary Steven Chu boasted to the nation’s governors at a February meeting that his department would be issuing categorical exclusions for some of the $80 billion in stimulus activities aimed at advancing cleaner-burning energy. The goal, he said, was to “get the money out and spent as quickly as possible.” There was little mention of environmental protection, or the fact that likely recipients of stimulus funds in the oil, gas, coal, and biofuel industries might have histories of violating environmental laws.

“We’re talking about billions of dollars here,” Chu told the governors. “It’s about putting our citizens back to work.”

Energy Department employees involved in NEPA reviews acknowledge that companies with “horrible” compliance histories — especially at the state level — can slip under their radar. They say the department lacks permitting and enforcement authority that would enable them to easily access such information. Even so, they say a company’s current and past environmental record is irrelevant.

“As a government, I feel we always have to give somebody a break. You’re always entitled to come back again,” said Fred Pozzuto, a department NEPA compliance officer. “We have to always be forgiving and look at this on a project-by-project basis.”

The Energy Department’s general counsel echoed the sentiment. “We know that some people have violated [environmental] regulations in the past. That’s not a shock to us,” Harris said, explaining that he’d give a categorical exclusion to a company “even if the CEO were indicted,” if the project warranted it.

Administration Created Exemptions After Congress Rejected Idea

The idea of granting blanket NEPA exemptions for stimulus recipients was first raised in Congress when the law was being crafted in early 2009. Industry groups claimed the environmental review process would hold up shovel-ready projects. Some governors called for greatly streamlining NEPA requirements.

Sen. John Barrasso, the Wyoming Republican, offered an amendment to the stimulus bill clearing projects whose NEPA reviews would take longer than 270 days. Two dozen industry groups sent senators a February 4, 2009, letter, backing the proposal, warning that “NEPA must be expedited in order to protect the projects and the jobs.”

Environmental advocates mounted a robust protest.

“Inevitably, in the course of congressional consideration, special interests will assert that we cannot afford the NEPA process in a time of national urgency,” 31 groups argued in a January 13, 2009, letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Rep. James Oberstar, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, and Sen. Barbara Boxer. “The truth is we cannot afford that kind of leap-before-you-look rashness.”

The green groups prevailed. Lawmakers declined to insert a broad exemption into the stimulus legislation. Instead, senators passed an amendment, negotiated by Boxer and Barrasso, mandating “expeditious” NEPA reviews using “the shortest existing applicable process.”

But what failed legislatively is now, in effect, happening administratively. Over the last year and a half, federal agencies have relied on regulatory fiat to create exemptions for stimulus projects under existing NEPA regulations, which allow for exclusions of whole categories of actions the government determines won’t “individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the human environment.”

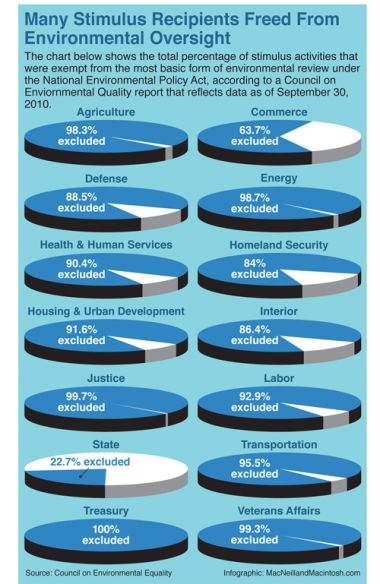

In filings with Congress, the administration has reported handing out categorical exclusions to 96 percent of stimulus projects so far — a total of 179,452. Among that total are nearly 4,800 new NEPA exemptions handed out in just three recent months, according to the latest report. By contrast, administration officials have required just 864 total projects to undergo the most comprehensive environmental review under the law.

The White House Council on Environmental Quality, which oversees the government’s compliance with NEPA, told the Center it does not keep historical records on NEPA reviews and could not say how the categorical exclusions for stimulus projects compared to those given to federal projects in past years.

The Energy Department, for its part, has granted NEPA exemptions to 99 percent of all stimulus projects it has funded so far, representing 8,012 actions costing $33 billion. Normally, according to Energy officials, the department requires about 10 percent of the projects that it funds to undergo some form of an environmental analysis, yet it has devised its own strategy for swiftly moving stimulus projects along.

Energy officials say the nature of the legislation — and its three-year timeline for doling out money — has yielded an emphasis on funding projects that would not automatically trigger a full environmental review, which can average two years to complete. “If it doesn’t require new construction,” one employee explained, referring to the categorical exclusion, “it’s pretty easy to CX.” They have first turned to proposals from firms seeking categorical exclusions because, as Harris explained, “you can go through the CXs more quickly.”

The department has also carved out regulatory exceptions for entire programs of stimulus money. For instance, with a single signature, one NEPA officer cleared all stimulus-funded projects to upgrade electrical grids with more efficient technology.

“The planned activities will involve the utilization of existing facilities and infrastructure to accomplish the goal of establishing a Smart Grid,” the officer’s July 7, 2009, decision explained.

The so-called Smart Grid Investment Grant Program involves many of the nation’s biggest-polluting utilities, including Westar and Duke. Companies that received the large grants along with NEPA exemptions say their projects are simply installing new equipment like smart meters and high-speed sensors on existing distribution systems, and therefore don’t threaten the environment.

“We’re basically adding communication infrastructure on top of what is already there so it is not disturbing the environment,” Duke spokeswoman Paige Layne said about the exemption the company got for a grid project that will eventually cost $204 million. That project has yielded 82 jobs so far.

Environmental advocates, however, say it is too simplistic to conclude that none of the 100 or so “smart grid” projects will harm the environment. They insist that exclusions should be made on the merits of each project, as the law envisioned.

“There is wide room for over-reliance on and outright abuse of the categorical exclusion process by federal agencies,” said Steven Mashuda, senior attorney at Earthjustice, who has challenged such decisions at other departments.

Energy officials counter that NEPA officers had to examine each project in order to discard the ones that did not fall under the broad exemptions. For example, they say they rejected all smart grid proposals calling for building new substations or digging up existing transmission lines.

They defend the overall NEPA screening process for stimulus activities as “extensive.” Review officers consider a project’s details, they say, as well as its funding objectives. Sometimes they consult the department’s project managers or the companies themselves. Other times they request additional documentation. “The CX is a NEPA review,” one officer said, albeit a “minimal” one.

Environmental lawyers disagree. “To say a categorical exclusion is a form of NEPA review is, to put it politely, rhetoric,” said Niel Lawrence, an NRDC senior attorney.

Environmental advocates suggest that intermediate levels of review might make sense in certain circumstances. One possibility, they suggest, would be to require every project that could have an environmental effect to undergo a less extensive review, known as an environmental assessment. Advocates see the assessment as kind of a screening test to ensure that a project does not require more intensive scrutiny.

“There are a lot of things the DOE has in its power that would provide incentive for a company to behave,” said Lawrence.

Lawrence and other environmental advocates also suggest Energy officials identify a “threshold” number of past or pending environmental violations that would automatically trigger a heightened NEPA review for any firm pursuing project funding.

‘Clean’ Does Not Always Mean ‘Green’

One of the most frequent arguments offered by department officials for the speedy processing of stimulus-funded clean energy projects is that they will help, not hurt, the environment. Some have expressed unwavering confidence that none of the NEPA-exempted projects would result in significant harm.

“I’d eat my hat if [NEPA officers] got something wrong,” Energy’s Harris told the Center, referring to the exclusions.

But the debate goes beyond the judgments of NEPA officers. According to documents, the Obama administration has unequivocally concluded that one of the Energy Department’s biggest stimulus outlays — a $1.37 billion loan guarantee for the massive Ivanpah solar power installation to be built on federal lands in California’s Mojave Desert — will negatively affect the environment.

The solar plant represents one of the few dozen stimulus projects required by the department to undergo the most comprehensive NEPA review. It was approved by both the department and Interior’s Bureau of Land Management earlier this year even after the environmental analysis had found that it would have a “direct, adverse” impact on 3,471 acres of prime habitat for the endangered desert tortoise, according to a copy of that study obtained by the Center.

The installation, undertaken by BrightSource Energy, has been scaled back to address some environmental concerns — reducing its footprint by 15 percent, for instance, and requiring 7,300 acres of “mitigation” to help deal with impacts. Yet the final “environmental impact statement” concludes that “there would still be long-term impacts to biological resources in comparison with the No Action Alternative.”

The final report also cautions that the project could worsen air quality in a pristine section of federally protected lands. The project, it states, “would still cause direct, adverse impacts to air quality …”

Administration officials have said that they believe efforts to alter the proposed solar installation to minimize pollution will keep it from violating NEPA. On October 7, the Bureau of Land Management cleared the stimulus project for construction. It was one of several massive, renewable energy projects the bureau had “fast-tracked” in order to enable companies to break ground before year’s end, thereby meeting a deadline to collect stimulus dollars.

Past Pollution Records Not A Factor In Most Exemptions

NEPA compliance officers have acknowledged that they couldn’t spend much time on the crush of stimulus applications. About 60 NEPA officers inside Energy were assigned to certify the thousands of categorical exclusions processed over the first 18 months.

Energy officials confirm the officers did not research applicants’ past pollution records; instead, they relied on information volunteered by companies in standard forms outlining their work, budget, and management plans. Applications included a questionnaire, about a dozen pages long, asking about potential effects on the environment, from radioactive waste to special wilderness areas.

An aerial view of Duke Energy’s coal-burning Gallagher Generating Station, in New Albany, Indiana. Duke paid $93 million to settle an air pollution case against the plant last year. Credit: John BlairHistorical violations were almost never a factor.

Didion’s stimulus grant for expanding its ethanol plant in Wisconsin offers a case study.

Less than a month before its approval, a federal judge ruled Didion’s plant had violated the clean-water law multiple times in recent years. In April, the company settled a state lawsuit by paying $1.05 million for 23 air and water claims dating back to 1999.

Today, the Environmental Protection Agency’s compliance database shows Didion receiving 11 violation notices since 2005 — among the most for any Wisconsin company. The agency has labeled it a “high priority violator.”

Nonetheless, Didion’s application to the Energy Department for a stimulus grant and NEPA waiver shows officials never sought — and Didion never disclosed — details of its environmental compliance record. In fact, the company did not answer several questions on the questionnaire.

For instance, the form asked what permits would be required, how solid waste would be hauled, and what emissions would result.

“Summarize the significant impacts that would result from the proposed project,” it said.

Didion left that one blank.

“That’s commonly not filled out by many companies, unfortunately,” explained Mark Lusk, the NEPA officer who approved Didion’s waiver.

Lusk and other officers recognize the “trust factor” inherent in the questionnaires. They try to verify a company’s answers, they say, consulting site maps and databases on soils or floodplains. What matters to them are the permit-related questions, which indicate major or new construction.

In Didion’s case, the company is installing new equipment at its ethanol plant, “things that are easy to do and should not have a negative impact,” Lusk said. He did not see any red flags in Didion’s case, he says, and did not look into the company’s past compliance problems.

Neither did Angela Harshman, the Energy Department employee who handled Didion’s stimulus grant. In a June 22 e-mail, she told the Wisconsin Center that background checks typically encompass “financial capability,” such as past audits, and “information via an environmental questionnaire.” Administration officials say those who monitor the stimulus dollars might flag previous environmental violations — if they involved potential criminal activity.

That would not include Didion’s million-dollar civil penalty to settle its violations.

Dale Drachenberg, the company’s vice president of operations, declined to comment on the stimulus grant and NEPA exemption, instead focusing on the project’s benefits. Didion will use 25 percent less power for every gallon of ethanol it produces, he said in a statement, and will hire 75 construction workers and 10 fulltime employees.

“Since the day we started construction on our ethanol production facility,” he said, “we’ve made innovation and conservation top priorities.”

To Karen Dettman, a neighbor of Didion’s plant in Cambria, Wis., who has lived with its spills and smells, the justification seems more like “green energy at any cost.”

Some NEPA Exemptions Are Conditional

Some of the department’s NEPA exemptions have been conditional, giving polluters initial permission to spend money on researching and developing a technology in a laboratory while leaving the door open for a second environmental analysis when the company breaks ground.

DuPont’s nearly $9 million stimulus project falls into that category.

Energy’s categorical exclusion decision, dated Jan. 29, explains DuPont is cultivating a “commercially viable process” to create seaweed-based biofuel that “offers significant advantages over fossil fuels and ethanol.” The form indicates the NEPA exemption was granted partly because the project entails “bench-scale research,” or experiments in a conventional laboratory setting. And it notes the project’s second phase — field testing described as “involving a 5-10 hectare macroalgae pilot aquafarm” — requires another NEPA decision before DuPont can proceed.

In its three-page questionnaire, DuPont reports that the project carries environmental risks, such as the use of “hazardous or toxic materials,” “additional chemical storage,” and “additional waste handling capabilities.”

“Does the proposed project have highly uncertain and potentially significant environmental effects or involve unique or unknown environmental risks?” the form asked.

DuPont checked “yes.”

Energy officials say they believe there was little risk in the first phase, and the second NEPA decision, which is now pending, will hinge on whether DuPont meets required milestones set for its initial lab work.

In a statement, DuPont stresses the company “has not applied for an environmental exclusion” for the project’s second phase, but rather is “following the necessary process set forth by the Department of Energy.” It states, “Each project that we work on includes, by our own policy, a comprehensive and individualized product stewardship program.”

That’s little consolation to environmental advocates who have long fought DuPont, and who believe the chemical giant can’t be trusted.

“It makes no sense to have environmental protection laws if we are going to circumvent them and exempt companies from having to follow them, especially companies like DuPont with long histories of pollution violations,” said Rick Abraham, a consultant who helped the United Steelworkers uncover high levels of the toxic chemical C8 in water supplies in a half dozen states with DuPont plants.

Such distrust is grounded in years of epic pollution battles. Kiger, the 62-year-old teacher who lives about a mile from a DuPont plant in West Virginia, remembers the day when a one-page letter arrived at his home from the local water service warning that traces of an “unregulated chemical” — C8 — had been found in the drinking water.

Tracing C8 to DuPont’s plant, which has used the chemical to make Teflon products since the 1950s, the letter called it “persistent” and “slow to be eliminated from the blood stream of people,” yet stated DuPont “is confident these levels are safe.”

“It was incredible,” recalled Kiger, who became a lead plaintiff in the first of three class-action lawsuits filed by West Virginia, Ohio, and New Jersey residents alleging DuPont’s C8 had contaminated their water. His suit ended in a $108 million settlement paid by the company to clean up six water districts and conduct a health study of 80,000 people.

Internal DuPont documents uncovered in the litigation triggered an EPA enforcement case in 2004 that would yield a record-breaking civil penalty. The documents showed DuPont had tracked C8 in neighboring water supplies at levels beyond its own safety standard years before Kiger received his letter. By December 2005, DuPont had settled the EPA case by paying $16.5 million for eight toxic substances and hazardous waste violations dating back to the early 1980s.

Two years later, the company agreed to pay nearly $70 million in penalties and remediation to resolve air-pollution claims against four of its sulfuric acid plants in four states. In April 2009, EPA pursued DuPont on allegations it illegally dumped mercury from a polymer fiber facility, imposing a $59,000 fine.

None of these violations were raised in DuPont’s November 2009 stimulus questionnaire. The office that awarded the company its grant and NEPA exemption has since revised its form to ask about “any notices of violations … related to health, safety, or the environment within the last three years.”

To Kiger, whose neighbors are still suing DuPont alleging ongoing C8 pollution, the NEPA exemption seems like another way for the company to game the system.

“That’s like giving a kid a piece of candy and telling him you cannot eat it,” he said.

Are “Smart Grid” Exemptions Smart?

The most sweeping NEPA exemptions, however, went to cover all grant recipients in the $4.5 billion smart grid program to make electrical grids more efficient. And they have created one of the most dramatic ironies in the debate over the administration’s strategy.

On March 26, EPA regulators filed a 72-page decree in a Kansas federal court formalizing a $500 million settlement of charges that Westar Energy had caused 16 years of unpermitted emissions of smog and haze, one of the Obama administration’s biggest air pollution victories.

That same day, the Energy Department signed yet another agreement with Westar, granting it millions in stimulus dollars for a smart grid project in its home state. The money — delivered on March 29 — came with a NEPA exemption.

Westar executives say Energy’s process for approving the company’s NEPA waiver involved a “comprehensive” questionnaire and “a fairly detailed analysis” of their smart grid project, known as “SmartStar,” which has yielded 12 jobs so far while saving others.

Brad Loveless, the company’s environmental director, describes the activities much like Energy officials: “It’s our basic, standard, above-ground upgrade,” he said. The department stresses that Westar’s project will make the electrical grid more efficient, thereby reducing the need for coal-fired power.

Westar’s questionnaire, dated August 2009, suggests the work has at least one environmental impact. The company reports it will handle “small amounts of mercury” contained in 1,750 old electric meters, recycling the toxic metal “as a universal waste.”

Loveless and fellow executives say they never discussed Westar’s past environmental violations with Energy officials during the process. According to department employees, every smart grid project was subject to a blind evaluation, meaning the NEPA officer did not know a company’s name or other identifying information.

Meanwhile, EPA was trumpeting its settlement with Westar. In February 2009, the agency sued Westar alleging the company had evaded permit requirements under the federal Clean Air Act, from 1994 to 1997, causing more than a decade of unauthorized air emissions at a coal plant outside Topeka.

Company executives say the five claims of air violations at the plant have no bearing on a stimulus project located in another region of the state. Westar “has never agreed with EPA’s contention,” they argue; it settled with the agency because it was already investing millions of dollars in scrubbers to curb air pollution at the plant.

“There’s a reasonable approach to considering a company’s record in the grant and waiver process, but that record should be looked at holistically,” said Westar’s Jim Ludwig. “I think we’ve clearly passed any kind of threshold.”

Yet the fact that Westar would be freed from environmental oversight so soon after it was penalized under the clean-air law has left some residents in disbelief.

“They haven’t proved they have the communities and their responsibilities for pollution as a top priority,” said Gary Anderson, a 67-year-old retired accountant who lives downwind from the company’s coal plant. “I don’t think we should leave it up to Westar to do what’s right.”

Before Gulf Spill, BP Refinery Won Stimulus Grant

BP’s ill-fated Texas City refinery — site of that deadly 2005 explosion — has also managed to qualify for a NEPA exemption for the first phase of a stimulus project. Under the grant, industrial gas maker Praxair has led an experiment to capture carbon emissions from the refining process and store them underground in nearby oil fields, to both enhance peak-oil production and reduce greenhouse gases linked to global warming.

In October 2009, the Energy Department awarded $1.5 million to Praxair for preliminary planning and data collection. The company, which was to construct carbon-compression facilities, brought in pipeline operator Denbury Resources as a partner to “potentially purchase the CO2,” as its August 2009 application states. BP was to provide land and “necessary utility infrastructure” at its refinery.

At the time — just eight months before the disastrous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico — BP was set to be fined an unprecedented $50.6 million by federal regulators for failing to fix safety hazards contributing to the 2005 refinery blast, which killed 15 workers and injured 170. The penalty would mean the oil giant had violated its criminal plea agreement over the incident. Denbury, too, was facing repeated notices of violations for a series of small pipeline spills, one of which yielded a $12,500 fine in 2008.

The department awarded the stimulus money for initial design and engineering work, as well as field testing for what would become a demonstration site for carbon capture. It granted Praxair the NEPA exemption in November 2009 for the project’s first phase, leaving open the possibility that an environmental review might be required if the project proceeded to a second phase.

In its questionnaire, Praxair estimates its early work would produce 10,000 pounds of non-hazardous “lab or sampling waste.”

Praxair declined to comment on the Texas City refinery’s record of environmental and safety violations, stating that the NEPA exemption was for an engineering study only. It did not pursue phase two because, Praxair explained, “the risks and uncertainties were not commensurate with potential benefits of the project at this time.” BP, for its part, stresses that it provided Praxair with the information it needed to complete its stimulus application for the first phase. “BP has had no further involvement,” said Scott Dean, a company spokesperson. And Robert Cornelius, director of operations for Denbury, told the Center, “We do take environmental compliance very seriously.” He attributed Denbury’s past fines to its practice of buying oil fields in disrepair, explaining that the company has invested $3.5 million in new equipment to prevent future spills.

Energy employees insist they would have conducted some form of an environmental review if the project had continued. In April, the company failed to apply for additional stimulus money to move into the next phase.

Still, the mere fact that the refinery received any stimulus money and a NEPA exemption alarms some involved in earlier battles with the refinery. “I wouldn’t let Charles Manson date my daughter, even if they claimed he was rehabilitated,” said Brent Coon, the Texas lawyer who represented victims of the BP refinery fire. “And BP can’t be taken by the government at its word.”

“At some point,” he said, “you have to recognize you cannot rehabilitate the offender.”

Temporary Construction Does Not Raise Red Flags

One thing that Energy officials say would disqualify any stimulus project from getting a NEPA exemption is new construction. Yet the department has spared Duke Energy’s $21.8 million wind-storage battery project — and its construction and installation work — from having to undergo an environmental review.

Energy’s categorical exclusion decision, dated March 16, explains Duke is constructing “a concrete pad to place four (4) tractor-trailer sized batteries upon,” each of which will store wind-generated power for existing turbines at the company’s Notrees Windpower Plant, in Goldsmith, Texas. The form indicates the NEPA waiver is partly for “R&D or pilot facility construction,” and lays out a restriction: “Keep all temporary roadway work near substation.”

Duke and Energy officials alike describe such work as benign: The container-like batteries will enable the company to distribute wind power during peak electrical demand, says Duke’s Greg Efthimiou. Pozzuto, the NEPA officer who approved the exemption, notes that the firm’s wind farm sits on a remote patch of disturbed land, the substation and turbines already in place.

“It’s essentially the same thing as a few tractor trailers pulling up to a restaurant,” he said, “and parking there for a while.”

In its questionnaire, dated August 2009, Duke estimates that the battery-storage unit “is approximately the size of 20 18-wheeler truck beds,” and acknowledges that “some land adjacent to the substation temporarily would be affected.” It stresses, “Any environmental impacts will be limited to this small footprint.”

To Duke and Energy officials, the stimulus dollars will help enhance the company’s renewable energy operations, thus reducing its coal plants’ environmental footprint. Some environmental advocates, on the other hand, cannot forget that Duke has spent the past 10 years contesting two of the biggest air-pollution cases in the nation.

In December 2000, the EPA sued Duke, alleging it had refurbished eight plants in North and South Carolina without proper permits, spewing illegal haze, smog, and soot for years. The suit has yielded multiple technical rulings, including one in 2007 from the U.S. Supreme Court. Company executives and lawyers involved in the suit agree Duke has been cleaning up the plants, largely because of a state law forcing it to do so.

Duke has fought equally hard in a second suit involving six plants in Indiana and Ohio owned by Cinergy, which merged with Duke in 2006. After a decade of legal twists, a jury in 2008 ruled against one of the plants. In a 59-page opinion, dated May 2009, a federal judge blasted Duke for what he called its “apparent inability to appreciate the relevance of the regulatory scheme and the jury’s verdict” by failing to cut the plant’s emissions following the verdict.

The judge ordered the company to shut down the facility, yet Duke appealed. On October 12, a federal appellate court reversed the jury verdict, ruling that Duke’s Cinergy had not been required to obtain permits under state regulations at the time. According to the appellate ruling, the reversal comes even though renovations at the plant had increased air pollution — and even though the state had amended its regulations to require a permit for such renovations — because federal regulators had yet to approve those amendments. Meanwhile, when the company lost another jury verdict over a second Indiana plant last year, it agreed to settle the air pollution violations by paying $93 million in penalties and remediation costs.

Company executives point out that the EPA originally claimed 55 air violations, yet has prevailed on six. And throughout the litigation, they say, Duke has invested $5 billion in scrubbers and cut the coal plants’ pollution by 70 percent.

“Our record on reducing emissions speaks for itself,” said Duke’s Tom Williams, “and we will continue to reduce emissions over time.”

Duke officials confirm the department did not discuss the air-pollution cases, or any environmental compliance issues, before clearing the wind storage project from NEPA.

“You cannot let something Duke Energy did at a plant in another state and on another issue hold up this particular project,” Pozzuto explained.

To Kerwin Olson, of the Indiana-based Citizens Action Coalition, the company’s aggressive defense of the air-pollution cases seems reason enough. “All Duke Energy does is fight regulations and work to remove environmental and health protections,” he said. “They do little to nothing to clean up.”

Kate Golden, staff writer at the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, contributed to this article.

Join the conversation

Show Comments