Introduction

In Osasco, Brazil, an industrial city on the western flank of Sao Paulo, the past is buried beneath a Wal-Mart Supercenter and a Sam’s Club at the intersection of Avenida MariaCampos and Avenida dos Autonomistas. Here the Eternit asbestos cement factory was shuttered in 1993 and demolished in 1995 after 54 years of operation. Here three generations of workers — pouring asbestos into giant mixers with cement, cellulose and water, emptying bags, cleaning machinery — were immersed in fiber-rich white dust, setting themselves up for diseases that would debilitate many of them in retirement and kill some of them in excruciating fashion. Scores have died since the mid-1990s, at least 10 of mesothelioma, a rare malignancy that eats into the chest wall and dispatches its victims swiftly. Aldo Vincentin succumbed at age 66 in July 2008, only three months after his diagnosis. “They knew about the dangers of the materials and they didn’t protect my husband,” his widow, Giselia Gomes Vincentin, says of Eternit. “I think many people will still die.”

Backed by a global network of trade groups and scientists, the multibillion-dollar asbestos industry has stayed afloat by depicting Osasco and similar tragedies as remnants of a darker time, when dust levels were high, exotic varieties of the fire-resistant mineral were used, and workers had little, if any, protection from the toxic fibers. There is evidence that dangers persist: Perilous conditions have been documented from Mexico City to Ahmedabad, India. And yet, despite waves of asbestos-related disease in North America, Europe, and Australia, bans or restrictions in 52 countries, piles of incriminating studies, and predictions of up to 10 million asbestos-related cancer deaths worldwide by 2030, the asbestos trade remains alive and well.

Asbestos is banned in the European Union. In the United States it is legal but the industry has paid out $70 billion in damages and litigation costs, and asbestos use is limited to automobile and aircraft brakes, gaskets and a few other products. The industry has found new markets in the developing world, however, where demand for cheap building materials is brisk. More than two million metric tons of asbestos were mined worldwide in 2009 — led by Russia, China, and Brazil — mostly to be turned into asbestos cement for corrugated roofing and water pipes. More than half that amount was exported to developing countries like India and Mexico.

Health officials warn that widespread asbestos exposures, much as they did in the West, will result in epidemics of mesothelioma, lung cancer, and asbestosis in the developing world. The World Health Organization (WHO) says that 125 million people encounter asbestos in the workplace, and the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that 100,000 workers die each year from asbestos-related diseases. Thousands more perish from environmental exposures. Dr. James Leigh, retired director of the Centre for Occupational and Environmental Health at the Sydney School of Public Health in Australia, has forecast a total of 5 million to 10 million deaths from asbestos-related cancers by 2030. The estimate is “conservative,” Leigh says. “If exposures in developing countries lead to epidemics extending further in time, the numbers would be greater.” Leigh’s calculation does not include deaths from asbestosis, a non-cancerous, chronic lung disease. Another study, by two researchers in New Delhi, suggests that by 2020, deaths from asbestos-related cancers could exceed 1 million in developing nations.

Behind the industry’s growth is a marketing campaign involving a diverse set of companies, organized under a dozen trade associations and institutes. Backing them are interests ranging from mining companies like Brazil’s SAMA to manufacturers of asbestos cement sheets like India’s Visaka Industries. The largely uncharted industry campaign is coordinated, in part, by a government-backed institute in Montreal and reaches from New Delhi to Mexico City to the aptly named city of Asbest in Russia’s Ural Mountains.

An analysis by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has tracked nearly $100 million in public and private money spent by these groups since the mid-1980s in three countries alone — Canada, India and Brazil — to keep asbestos in commerce. Their strategy, critics say, is one borrowed from the tobacco industry: create doubt, contest litigation, and delay regulation. “It’s totally unethical,” says Jukka Takala, director of the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work and a former ILO official. “It’s almost criminal. Asbestos cannot be used safely. It is clearly a carcinogen. It kills people.”

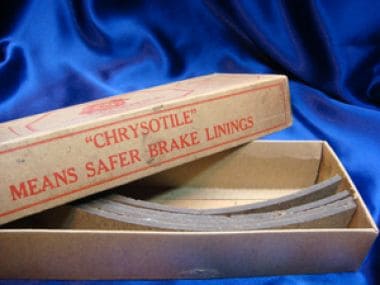

Industry-funded researchers have mounted a prolific response, placing into the scientific literature hundreds of articles claiming that asbestos can be used safely. Their argument is that chrysotile, or white, asbestos — the only kind sold today — is orders of magnitude less hazardous than brown or blue asbestos, which the industry stopped mining in the 1990s. “It’s an extremely valuable material,” argues Dr. J. Corbett McDonald, an emeritus professor of epidemiology at McGill University in Montreal who began studying chrysotile-exposed workers in the mid-1960s with the support of the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association. “It’s very cheap. If they try to rebuild Haiti and use no asbestos it will cost them much more. Any health effects [from chrysotile] will be trivial, if any.”

Health and labor officials recoil at such statements. “No exposure to asbestos is without risk,” the Collegium Ramazzini, an international society of scholars on occupational and environmental health, said in a recent paper. “Asbestos cancer victims die painful, lingering deaths. These deaths are almost entirely preventable.”

Last fall, the American Public Health Association joined the Collegium, the World Federation of Public Health Organizations, the International Commission on Occupational Health, and the International Trade Union Confederation in calling for a global asbestos ban. In 2009, a panel of 27 experts convened by the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer reported, “Epidemiological evidence has increasingly shown an association of all forms of asbestos … with an increased risk of lung cancer and mesothelioma.” The panel also found there was new evidence that asbestos causes cancer of the larynx and the ovary.

But the asbestos industry has signaled that it will not go away quietly. Promotion of pro-industry studies is joined by campaigns of political lobbying and ad buying to ensure that asbestos is freely marketed in fast-growing countries. Consider some of the events just this year: In a March 16 letter, the head of the Asociación Colombiana de Fibras, a chrysotile trade group in Bogotá, Colombia, asked World Bank president Robert Zoellick to “soften your position” on the compound, arguing that projections of 100,000 asbestos-related deaths a year were based on “old data.” (The bank announced last year that it expects borrowers to use asbestos alternatives whenever feasible.) In documents obtained in Colombia by ICIJ, the association boasts of creating a spinoff in Ecuador to try to shape government regulations and decries the emergence of the “international prohibitionist movement” against asbestos. “We have to start a wide campaign among all the chrysotile associations in the world to counteract [the movement], sending communications to the directors of the World Health Organization and International Labor Organization,” state the minutes of a 2008 board meeting.

In a Jan. 7 letter, a lawyer for India’s Asbestos Cement Products Manufacturers Association scolded Dr. T.K. Joshi, an occupational medicine specialist in New Delhi, for making “baseless” allegations against chrysotile and frightening workers. The lawyer demanded that Joshi retract his “yellow reporting” or, he implied, face legal action. A few weeks earlier, the association had placed an ad in The Times of India, that nation’s leading English daily, headlined, “Blast Those Myths About Asbestos Cement.” The ad claimed, among other things, that the cancer scourge in the West had come during a “period of ignorance,” when careless handling of asbestos insulation resulted in excessive exposures. Such exposures are long gone, the ad said, noting that asbestos cement products are “strong, durable, economical, energy efficient and eco-friendly.”

A troubled history

Fire- and heat-resistant, strong and inexpensive, asbestos — a naturally occurring, fibrous mineral — was once seen as a construction material with near-magical properties. For decades, industrialized countries from the United States to Australia relied on it for countless products, including pipe and ceiling insulation, ship-building materials, brake shoes and pads, bricks, roofing, and flooring.

Ominous reports about the health effects of asbestos began appearing in Europe in the late 19th century. By 1918, American and Canadian insurance companies were refusing to cover asbestos workers because of rampant lung disease. In 1930, the ILO issued a warning: “All [asbestos] processes from extraction onwards unquestionably involve a considerable hazard.” In 1960, a South African pathologist confirmed a direct link between asbestos exposure and mesothelioma. And yet, uncontrolled use of asbestos only grew, peaking in the United States in 1973. By one estimate, 100 million Americans were occupationally exposed to asbestos during the 20th century.

The first asbestos lawsuit against an asbestos insulation manufacturer in the United States was filed in 1966. Internal documents showing corporate knowledge of the mineral’s lung-ravaging properties began to surface, and by 1981 more than 200 companies and insurers had been sued. The following year, the nation’s biggest maker of asbestos products — Johns Manville Corp. — and two other defendants filed for bankruptcy protection in an effort to hold off the tide of litigation. From the 1960s through 2002, more than 730,000 people filed asbestos claims, resulting in damage payments and litigation costs of $70 billion, according to a 2005 study by the RAND Corp. Of this, $30 billion actually went to claimants.

As the evidence against asbestos accumulated in the 1980s, the Scandinavian countries began to impose bans. But the biggest blow for chrysotile came in 1999, when the European Commission decreed that products made of white asbestos would be outlawed as of Jan. 1, 2005. The EU’s decision to ban was replicated by Chile, Australia, Japan, and Egypt, among other countries. Most flatly forbid use of asbestos, though a few still allow it in brakes and gaskets. Fifty-two countries eventually slapped restrictions on its use, including most of the developed world. Less hazardous but generally more expensive substitutes such as polypropylene fiber cement, aluminum roof tiles, and steel-reinforced concrete pipe have gained favor.

Yet chrysotile continues to be mined and used heavily in some parts of the world; in 2008, raw fiber exports worldwide were valued by the United Nations at nearly $400 million. Russia is the world’s biggest producer, China the biggest consumer. But Canada — which uses almost no asbestos within its borders but still ships it abroad — is the primary booster, a role it assumed in the 1960s when the country’s mining industry in Quebec was threatened by studies tying the mineral to cancer. The federal and provincial governments together have given C$35 million over the past quarter-century to the Montreal-based Chrysotile Institute, a nonprofit group that promotes the “controlled” use of asbestos in construction and manufacturing.

Controlled use is elusive in developing nations. ICIJ inquiries in a half-dozen countries, including on-site visits and interviews with local health officials and worker advocates, found spotty protection measures and widespread exposure to asbestos dust. This will likely produce outbreaks of occupational disease for years to come in places like India, China, and Mexico, experts say. “Anybody who talks about controlled asbestos use is either a liar or a fool,” says Barry Castleman, an environmental consultant based near Washington, D.C., who advises the WHO on asbestos matters. “If they can’t have controlled use in Sweden, they can’t have controlled use in Swaziland.”

The Chrysotile Institute

At the center of the debate is the Canadian government-backed Chrysotile Institute. The institute’s president, Clement Godbout, insists that his organization’s message has been misinterpreted. “We never said that chrysotile was not dangerous,” he says. “We said that chrysotile is a product with potential risk and it has to be controlled. It’s not something that you put in your coffee every morning.”

The institute is a purveyor of information, Godbout emphasizes, not an international police agency. “We don’t have the power to interfere in any countries that have their own powers, their own sovereignty,” he says. “We don’t have the resources to travel the world every day.” Godbout says he is convinced that large asbestos cement factories in Indian cities have good dust controls and medical surveillance, though he acknowledges that there might be smaller operations “where the rules are not really followed. But it’s not an accurate picture of the industry. If you have someone on a highway in the U.S. driving at 200 miles per hour, it doesn’t mean everybody’s doing it.”

The Chrysotile Institute has received $1 million from the asbestos industry over the past five years, according to Godbout, who says he doesn’t know how much was contributed in the previous 20, before he became chairman. Documents obtained under Canada’s Access to Information Act by Ottawa researcher Ken Rubin indicate that the industry gave more than $18 million to the institute from 1984 through 2001, meaning its total contribution to Godbout’s group is probably around $20 million.

The institute offers what it describes as “technical and financial aid” to a dozen sister organizations around the world. These organizations, in turn, seek to influence science and policy in their own countries and regions. Consider the situation in Mexico, which in 2007 used 10 times as much asbestos as its neighbor, the United States. Promoting chrysotile use is Luis Cejudo Alva, who has overseen the Instituto Mexicano de Fibro Industrias (IMFI) for 40 years. Cejudo says he is in regular contact with the Chrysotile Institute and related groups in Russia and Brazil, and gives presentations inside and outside of Mexico on the prudent handling of chrysotile. “If I knew that our industry kills people, that our products affect the population, I wouldn’t be here talking to you,” Cejudo says. “I am here because I have realized that many asbestos detractors exist, especially in Europe.” In the 1990s, he notes, IMFI members, along with their Canadian and American counterparts, agreed to stop selling asbestos to factories without adequate safety measures; this led to some plant closures. “We work hard with the government Health and Labor ministry representatives to create the regulations and to make constant visits to prove that the factories are following these regulations,” Cejudo says.

A more skeptical perspective comes from Dr. Guadalupe Aguilar Madrid, a physician and researcher at the Mexican Social Security Institute, which oversees public health under the federal Secretariat of Health. Aguilar maintains that the IMFI exists not to promote safety but to preserve the chrysotile market in Mexico. It has insinuated itself into both the Labor and Health secretariats, she said, and has had a “very big” influence over workplace and environmental rules. “When asbestos was banned in industrialized countries and [producers] started to lose money, they came to the developing countries to recover their investments,” Aguilar says. “After some South American countries banned asbestos, they focused on Mexico as their main manufacturer.”

Mexico ramped up imports of Canadian chrysotile in the 1970s, and its weak worker-protection laws have allowed dangerous conditions to proliferate, Aguilar says. About 70 factories in and around Mexico City manufacture asbestos cement, and an indeterminate number make asbestos brakes, boilers, and other products, according to Aguilar. All told, she estimates that 10,000 Mexicans work with asbestos at any one time, many without proper protection. As a result,Mexico can expect an epidemic of mesothelioma in coming years, Aguilar says. Her research shows that the number of deaths is rising steadily, as would be expected given the 30- to 40-year latency period commonly associated with the disease. Including mesothelioma and lung cancer, “we could be talking about 3,000 to 5,000 deaths from diseases related to asbestos every year,” the doctor says. She calls Canada’s chrysotile exports “deplorable.”

Another sister organization is the Brazilian Chrysotile Institute, based in the state of Goiás, site of the country’s only asbestos mine. A prosecutor in the state is seeking dissolution of the institute, a self-described public interest group with tax-exempt status. The prosecutor charges in a court pleading that the institute is a poorly disguised shill for the Brazilian asbestos industry, which provides virtually all its budget. Among other things, the group helped the Brazilian government fund studies rigged to benefit the industry, the prosecutor alleges. Having inflicted “social damage stemming from [its] illegal practices,” the institute should pay one million reais (about $550,000) in damages and a fine of 5,000 reais ($2,800) for every day it remains open, the pleading says. In a statement to ICIJ, a spokesman for the institute denied the allegations, saying the group “ensures the health and security of workers and users, protection of the environment and [provides] information to society.” Public records show that the institute has taken in more than $8 million from asbestos companies since 2006.

That a Brazilian prosecutor is even attempting to shut down the institute is unusual. Most if not all of the pro-chrysotile groups have friendly relationships with their host governments and appear to easily overpower public health advocates. In Russia,which produced one million metric tons of chrysotile in 2008, more than any country by far, Prime Minister Vladimir Putin pledged to assist the industry after a plea for help from a trade union chief. Putin “promised to support Russian producers of chrysotile, especially in situations where we find ourselves under political pressure at the international level,” Andrei Kholzakov, chairman of the union that represents workers at one of the country’s largest asbestos companies, Uralasbest, said in an April 2009 press release.

Perhaps nowhere is the industry as strong as in India, the world’s second-largest consumer of asbestos, after China. There are more than 400 asbestos cement factories in the Indian state of Gujarat alone, concentrated in the city of Ahmedabad, and the national market is growing at the rate of 30 percent a year, due mainly to construction in poor, rural areas, where asbestos sheet is standard cover for homes.The Asbestos Cement Products Manufacturers Association enjoys a “tight relationship” with federal and state politicians, says activist Madhumita Dutta. The state in which she lives, Tamil Nadu, owns an asbestos roofing materials plant, Dutta says, and there are similar arrangements in other states. “Things are a bit bleak,” she wrote in an e-mail to ICIJ. “The industry has grown and is expanding, their political clout getting stronger, their direct interventions in the government decision-making more apparent (through funding government studies), their propaganda more aggressive.” Government sources told ICIJ that the manufacturers’ association has received about $50 million from the industry since 1985, with annual allotments rising as anti-asbestos sentiment escalated. One of the group’s specialties is “advertorials” — faux news articles that extol the safety and value of asbestos products. The association’s annual budget now ranges from $8 million to $13 million, according to one member.

The ACPMA says on its website that the use of chrysotile in manufacturing “is safe for the workers, environment and the general public.” Earlier this year, however, authorities brought four criminal cases against owners of a 48-year-old asbestos cement factory in Ahmedabad, Gujarat Composite Ltd., alleging egregious health violations. At least 75 employees of the company have developed lung cancer over the past decade.

Though there are many uncertainties, researchers say that China appears poised for an explosion of asbestos-related illness in the not-too-distant future. Based on a formula developed by Antti Tossavainen with the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health — that one mesothelioma case occurs for every 170 tons of asbestos produced and consumed — at least 3,700 cases of the disease can be expected each year, not to mention thousands of cases of lung cancer, asbestosis, and stomach cancer. China has yet to see the level of disease experienced in Europe, the U.S. and other industrialized parts of the world, experts say, because per capita consumption of asbestos remained low into the 1970s. That’s no longer true, as China is now the world’s biggest user of the mineral. Takala, director of the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, estimates that 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese will die of asbestos-related ailments each year by 2035. The country has about 1,000 asbestos mines and production facilities, one million asbestos workers, and annual consumption of more than 600,000 metric tons of chrysotile.

Canada’s controversial role

No country has defended chrysotile as vigorously, and for as long, as Canada. When the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a rule banning asbestos in 1989, the government of Canadaparticipated inan industry lawsuit that overturned the rule. When France banned asbestos a decade later, Canada teamed up with Brazil in an unsuccessful World Trade Organization challenge. And when a United Nations chemical review committee recommended in 2008 that chrysotile be listed under Annex III of theRotterdam Convention — a treaty thatrequires exporters of hazardous substances to use clear labeling and warn importers of any restrictions or bans — Canada, India, and a few other nations kept the recommendation from winning the unanimous support it needed to pass.

It was the fourth time since 2004 that chrysotile had come up for consideration and the fourth time it had failed to make Annex III. It probably won’t come up again until 2011 at the earliest. “We knew it was not going to go through smoothly and unopposed,” says Sheila Logan with the United Nations Environment Programme, who was in the thick of negotiations on chrysotile in 2006. Annex III, Logan explains, is a “semi-blacklist, though there are many substances on there that many countries will continue to import. The fear [among exporters and users] is that countries will just take a blanket approach and say, ‘No, I’m not importing anything that’s included in the convention.’” Logan says she believes that chrysotile should be listed, even if — as some scientists claim — it is less carcinogenic than blue or brown asbestos, both of which belong to a family known as amphiboles. She draws an analogy: “An X-ray may be less dangerous than a gamma-ray burst, but I’m not going to stand in front of either of them. That’s my personal choice.”

Canada today is the world’s fifth largest producer of asbestos and its fourth largest exporter, shipping $97 million of raw fiber overseas in 2008. All this comes from just two mines, both located in Quebec. The Chrysotile Institute says the industry accounts for about 700 direct and 2,000 indirect jobs — hardly an economic juggernaut. But it survives despite mounting criticism: Both the federal and provincial governments have been besieged by letters from prominent academics, physicians, and others protesting Canada’s export of chrysotile. In a statement to ICIJ, the Quebec Ministry of Natural Resources made its case: “There are no valid reasons to halt chrysotile export since it can be used safely. [D]eveloping countries are in great need of this kind of material (as we were some years ago) to build good infrastructures. Furthermore, substitutes to chrysotile have not yet been proven to be safer.” In addition to funding the Chrysotile Institute, the ministry has given C$748,000 since 2004 to the Société Nationale de l’Amiante, an asbestos research group. No longer active, the group relocated its office to the ministry, which is in the process of settling its “past commitments and responsibilities,” a government spokesman said.

Christian Paradis, natural resources minister in Canada’s conservative government, is similarly supportive of the industry. Anative of the town of Thetford Mines, Quebec,Paradis once served as president of theAsbestos Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “Since 1979, the Government of Canada has promoted the safe and controlled use of chrysotile, [and] our position remains the same,” Paradis said in a statement to ICIJ. “Banning chrysotile is neither necessary nor appropriate. … All recent scientific studies show that chrysotile fibers, the only asbestos fiber that is produced and exported from Canada, can be used safely under controlled conditions.”

Fine for export, perhaps, but not for domestic use. In 2009, Canada sent nearly 153,000 metric tons of chrysotile abroad. More than half went to India; the rest went to Indonesia, Thailand, Mexico, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. At home it was a different story: Canada used only 6,000 tons domestically in 2006, the last year for which data are available. Canadian officials seem determined to boost production: The Quebec Ministry of Economic Development, Innovation and Export Trade is considering a C$58million loan guarantee to save the floundering Jeffrey Mine. The mine’s owner has announced plans to ship 200,000 tons of chrysotile per year to Asia if the money comes through.

Amir Attaran, an associate professor of law and medicine at the University of Ottawa, says he is ashamed of the nation’s stance. “It’s absolutely clear that [Prime Minister] Stephen Harper and his government have accepted the reality that the present course of action kills people, and they find that tolerable,” Attaran says. “Canada’s certainly aware that countries which purchase chrysotile do so in the absence of correct regulation.”

The scientists

On March 10, David Bernstein stepped up to the podium at the Society of Toxicology’s annual meeting in Salt Lake City, Utah, and announced the results of his latest study. An American-born toxicologist based in Geneva, Bernstein began researching chrysotile in the late 1990s at the behest of a mine operator in Brazil. He was now reporting that rats exposed to chrysotile asbestos for five days, six hours a day, had shown no ill effects whatsoever. Rats exposed to brown amosite, a type of amphibole, hadn’t fared so well. The chrysotile fibers were cleared quickly from the animals’ lungs and caused “no pathological response at any point,” even though the exposure level was 50 percent higher than that for amosite, Bernstein said. The fibers have very different appearances under magnification. Chrysotile fibers look like ultrathin, rolled sheets; amosite and other amphiboles look like solid rods.

The sponsor of the as-yet unpublished study was Georgia-Pacific Corp. of Atlanta, which once made a ready-mix joint compound — a gooey white substance used to seal joints between sheets of drywall — that contained 5 percent chrysotile. Georgia-Pacific has been sued in the United States by a number of mesothelioma victims who claim they were exposed to asbestos while sanding the dried compound. Bernstein’s latest study, done in conjunction with Georgia-Pacific’s chief toxicologist, Stewart Holm, could be good news for the company.

Bernstein is the most active of a dozen or so industry-backed scientists who have helped fuel the asbestos trade by producing papers, lecturing, and testifying on the relative safety of chrysotile. The industry has spent tens of millions of dollars funding their studies, which have been cited some 5,000 times in the medical literature as well as by lobby groups from India to Canada. Bernstein’s work alone has been cited 460 times. He has been quoted or mentioned in Zimbabwe’s Financial Gazette, Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post and other publications around the world. His curriculum vitae suggests that he’s been a one-man road show for chrysotile, giving talks in 19 countries since 1999. Among his stops: Brazil, China, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Korea, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam. The industry paid for all of his travel, Bernstein told ICIJ in an interview.

Indeed, all of Bernstein’s work on asbestos has been underwritten by the industry, and he has become its principal defender at scientific meetings and in other venues. Bernstein says he has no idea how much all his studies have cost and emphasizes that, in any case, most of the money goes to the laboratory in Basel, Switzerland, where the animal experiments are performed. Court documents show that one sponsor, Union Carbide, paid $400,623 for work by Bernstein in 2003 and 2005.

In an interview in his hotel lobby the day before his presentation in Salt Lake City, Bernstein said that Georgia-Pacific in no way influenced his chrysotile research, nor have any of his other corporate sponsors. “I would work for any group,” Bernstein explained. “I have no limitations. Unfortunately, the groups that don’t like this work don’t ask me.” He decried the hyperbole surrounding chrysotile — “It’s a hysterical thing; it doesn’t come from science” — and said he doesn’t believe the fragile white fibers cause mesothelioma. They could cause lung cancer, he said, if exposures were extremely high.

The relevance of Bernstein’s rat experiments to humans is contested by fellow researchers. For example, an expert panel assembled by the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry concluded that rodents clear short asbestos fibers from their lungs about 10 times faster than do people. Bernstein’s animals, moreover, were exposed over a relatively brief period of time. Many workers inhale asbestos over months or years, not days. “Not everyone exposed, even heavily, will necessarily develop disease, but data in the scientific literature show that as little as one day of exposure in man and animals can lead to mesothelioma, and a month or less of exposure in man doubles the risk of lung cancer,” says Dr. Arthur Frank, a physician and professor at the Drexel University School of Public Health in Philadelphia.

If Bernstein is chrysotile’s scientific ambassador, then 92-year-old J. Corbett McDonald is its longest-tenured champion. He is the author of three dozen scientific papers on chrysotile, and his work has been cited in the medical literature nearly 1,500 times. In a telephone interview, McDonald said he was approached by the Canadian government in 1964to study asbestos miners and millersin Quebec; he, in turn, appealed to the Quebec Asbestos Mining Association for funding, which it agreed to provide. The impetus for the research, McDonald said, was a paper by Dr. Irving Selikoff of New York’s Mount Sinai School of Medicine reporting that insulation workers with relatively light exposures to asbestos were dying of mesothelioma and other cancers at strikingly high rates.

A lesson from tobacco?

Minutes of the mining association’s November 1965 meeting, obtained by lawyers for asbestos victims, suggest that the group saw the tobacco industry as a paradigm: “The consensus of opinion seemed to point out that the QAMA should take into its hands the ways and means to conduct the necessary research instead of doing it through universities or letting it fall in the hands of the Government. As an example, it was recalled that the tobacco industry launched its own program and it now knows where it stands. Industry is always well advised to look after its own problems.”

Forty-five years later, McDonald remains resolute in his defense of asbestos. He says there is “very strong evidence” that contaminants in chrysotile, and not the chrysotile itself, caused excesses of mesothelioma among the Quebec workers. The toxic agent, he suspects, was tremolite, a type of amphibole. McDonald insists that his work was never influenced by the asbestos industry. Indeed, he wasn’t sure how much its leaders even cared about his work. “It used to worry us a bit that they took so little interest in the results,” he says.

McDonald’s tremolite theory — rebutted by studies of textile workers exposed to almost pure chrysotile, and just this year, a study of workers at a brake-lining factory — follows a pattern that Dr. David Egilman, a physician and clinical associate professor at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, calls ABC: anything but chrysotile. In fact, some researchers and defense lawyers have argued that mesothelioma could be triggered by a polio vaccine contaminated with a monkey virus. “Like the tobacco industry, they’ve been successful at manipulating scientific theories to confuse the public about the real risks of using asbestos,” says Egilman, who, like Frank and Castleman, testifies on behalf of plaintiffs in asbestos lawsuits.

Bernstein’s and McDonald’s studies have proved helpful to an industry under growing pressure to disband. Amphiboles such as the virulent blue crocidolite, which killed miners in South Africa for nearly two centuries before the nation imposed a ban in 2008, are virtually never encountered today. There are obvious economic incentives, skeptics say, to blame most of the asbestos disease in the past 50 years on obscure types of the mineral and imply that chrysotile, which accounts for 95 percent of all the asbestos ever used, is relatively benign.

“Is there a legitimate scientific question as to whether white asbestos is less dangerous [than blue or brown]? Yes,” Frank says. “But is it safe? No.”

Several key criticisms have been leveled at the researchers who defend chrysotile. They tend, for example, to focus on mesothelioma — the disease that comes up most often in litigation because it is considered amarker of asbestos exposure — and ignore lung cancer, which occurs more frequently. ”Chrysotile is just as potent [as amphiboles] in terms of lung cancer, and it might even be more potent,” says Peter Infante, former director of the Office of Standards Review at the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. They fixate on the amount of time chrysotile fibers spend in the lungs, failing to acknowledge that the fibers can do a figurative hit-and-run on cells, damaging DNA and precipitating cancer. And they buy into what WHO consultant Castleman calls the fallacy of controlled use — the idea that employers in the developing world are serious about dust suppression and ventilation.

Castleman has been researching asbestos cement substitutes — roofing and pipes made with cellulose fibers, ductile iron and fiberglass, for example — for the WHO and has determined that, at most, they cost 10 to 15 percent more to produce. By his reckoning, asbestos is not much of a bargain. “Obviously, the cost of death and disease and the eventual cost of even halfway properly managing asbestos cement structures wipes out any short-term savings of 10 to 15 percent,” Castleman says. As for another industry claim — that substitute products may be more dangerous than chrysotile — he notes, “They do not release carcinogenic dust whenever they are sawed, drilled, and demolished.”

Despite the reassuring studies and the million-dollar marketing efforts, the asbestos industry faces stiffening headwinds. The number of countries imposing bans or restrictions continues to climb, and groups of health and labor activists have sprung up in China, Brazil, India, and other high-use countries. The government of Canada, long considered a leader on environmental and health matters, has come under withering attack for pushing exports.

For his part, scientist Bernstein contends that his conclusion is the correct one: White asbestos can be used safely around the world. That the WHO, the European Union, and dozens of national governments disagree doesn’t bother him. “It’s not in my interest whether it’s the minority view or not,” Bernstein says. “I’ve always felt that science will prevail at the end.”

Ana Avila in Mexico City, Dan Ettinger in Washington, D.C., Carlos Eduardo Huertas in Bogota, Murali Krishnan in New Delhi, Roman Shleynov in Moscow, and Marcelo Soares in Sao Paulo contributed to this report.

Join the conversation

Show Comments