Introduction

In 1998, unbeknownst to most Americans, the United States had a military presence in a remote African war that drew little attention from the media. Unlike other U.S. interventions in Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti and Kosovo, there was no hand-wringing over whether a deployment was justified by U.S. national interests, whether troops would be spread too thin, whether American men and women should be put in harm’s way in a fight that had little to do with Main Street America, or whether the level of barbarity justified, on its own merits, the deployment of U.S. troops on humanitarian grounds.

The conflict in Sierra Leone, in which the rebels of the Revolutionary United Front displayed a ghastly predilection for amputating the limbs and noses of their victims, could certainly compete with the horrors of “ethnic cleansing” in Bosnia and Kosovo and the man-made famine engineered by warlords in Somalia. In November 1998, the RUF was in the middle of an orgy of looting, murder and decapitation, an operation codenamed “No Living Thing.”

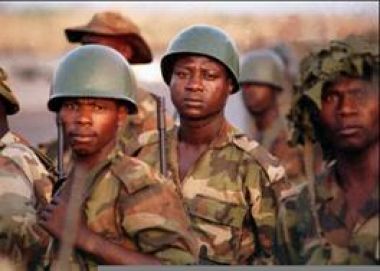

There was international intervention aimed at stopping the bloodshed. Sierra Leone’s demoralized and under-equipped national army was bolstered by Nigerian troops – flying the colors of the West African peacekeeping force, ECOMOG – and a handful of South African mercenaries in helicopter gunships who made constant forays into the battle zones to attack the RUF. In Freetown, the country’s capital, two large transport helicopters circled in the air, backing up the Nigerian troops.

This small U.S. contribution to defending Sierra Leone was not conducted by an elite unit of the Army, Navy or Marines, but by a private, Oregon-based company, International Charter Incorporated of Oregon (ICI), managed in part by former U.S. Special Forces operatives. ICI is one of several companies contracted by the State Department to go into danger zones that are too risky or unsavory to commit conventional U.S. forces. It also has been active in conflicts in Haiti and Liberia.Painted on their fuselages were American flags.

ICI’s role in Sierra Leone was to back up the Nigerian troops, providing transport and medical evacuation services. The hot combat, as one former ICI employee explained to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, was left to the South African mercenaries. But ICI personnel inevitably and often were shot at and forced to return fire, according to team members interviewed by ICIJ, a right these sources claimed was explicitly extended to ICI in a letter from then-U.S. ambassador to Sierra Leone, Joseph Melrose.

The State Department did not respond to requests for comment by telephone or through the Freedom of Information Act on whether such a letter was issued. ICI refused to respond to a number of questions put to the company on several occasions.

The United States had little real interest in Sierra Leone itself. U.S. involvement was driven by the fear that the instability and anarchy caused by the RUF and its sponsor, Liberian President Charles Taylor, would prove a danger to Washington’s ally Nigeria, an oil-rich nation that is the fifth largest supplier of crude to the United States. For ICI, the mission to Freetown was business, but it also advanced U.S. foreign policy.

ICI’s deployment is part of a global trend of military outsourcing and foreign policy by proxy that has become far more common since the end of the Cold War. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the nature of international conflict shifted from U.S.-Soviet competition in client states to regional and ethnic conflicts requiring peacekeeping or other engagement. At the same time, the end of Cold War resulted in reduced superpower defense budgets, forcing even high-ranking military officers to sell their talents in the public sector. This collision of supply and demand resulted in a new age of military and security services on the world market.

In fact, a nearly two-year investigation by ICIJ identified at least 90 private military companies, or PMCs (as some of these new millennium mercenaries prefer to be known), that have operated in 110 countries worldwide. Most of these companies – defined as providing services normally carried out by a national military force, including military training, intelligence, logistics, combat and security in conflict zones – are headquartered in the United States, Britain and South Africa, though the vast bulk of their services are performed in conflict-ridden countries in Africa, South America and Asia. Eleven of the companies identified by ICIJ are no longer active, and the operational status of 18 others could not be determined.

“Mercenaries” are officially outlawed under Article 47 of the Geneva Convention, which defines them as persons recruited for armed conflict by or in a country other than their own and motivated solely by personal gain. However, few modern PMCs fit that definition and, indeed, spokesmen for such companies insist they rarely engage in combat and provide military skills only to legitimate, internationally recognized governments. The ICIJ investigation found that a wide range of companies – from large corporations that offer military training, security, landmine clearance and military base construction to start-up entrepreneurs offering combat services and tactical training – are in what has become the complex and multibillion-dollar business of war.

Since 1994, the U.S. Defense Department has entered into 3,061 contracts with 12 of the 24 U.S.-based PMCs identified by ICIJ, a review of government documents showed. Pentagon records valued those contracts was more than $300 billion. More than 2,700 of those contracts were held by just two companies: Kellogg Brown & Root and Booz Allen Hamilton. Because of the limited information the Pentagon provides and the breadth of services offered by some of the larger companies, it was impossible to determine what percentage of these contracts was for training, security or logistical services.

Traditionally, the U.S. government provided military training to foreign governments directly. That changed in 1975, when Virginia-based military construction company Vinnell Corp. won a $77 million contract to train the Saudi Arabian National Guard to protect oil fields. The Saudi deal is considered the first time a U.S. civilian company obtained an independent contract to provide a foreign government with military services, a development initially greeted by significant media skepticism and vitriolic debate. Since then, the contract has been renewed with far less attention. Copies of 1991, 1995 and 2000 contracts, obtained by U.S. News & World Report and reviewed by ICIJ, show a total estimated value of nearly $500 million, and include training in counter-intelligence, “chemical defense” and other areas of operational security. Vinnell refused to comment on the contracts. From 1995 to 2000, subsidiaries of Vinnell’s parent company BDM reportedly obtained more than $150 million in contracts to provide logistical support and other services to the Saudi air force.

The U.S. Defense Department has increasingly turned to outside vendors for logistical support, one of the most heavily out-sourced sectors for the armed forces in both peacekeeping and wartime. In Bosnia, for example, the ratio of contractors to American soldiers has ranged from one in 10 to nearly one-to-one, according to various defense analysts. The trend gained momentum after the 1991 Gulf War, in which troops were heavily supported by a panoply of private contractors. A 1995 report of the Defense Science Board, a standing committee that advises the Pentagon on technological, scientific, and other issues, suggested that the Pentagon could save up to $6 billion annually by 2002 if it contracted out all of its support functions to private vendors, except those that deal directly with war fighting. The trend has persisted, as evidenced by a 2002 state-of-the-military review in which Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld emphasized the success of the department’s outsourcing of non-core responsibilities, stating that he would “pursue additional opportunities to outsource and privatize.”

Brown & Root is hardly the only PMC that raises questions about the revolving door. Frank Carlucci, who served as defense secretary in the waning years of the Reagan administration, was chairman of BDM when it acquired Vinnell; he is still chairman of the Carlyle Group, a merchant banking firm that owns BDM and counts a plethora of former government officials, including former President George H.W. Bush, his secretary of state, James Baker, and his director of the Office of Management and Budget, Richard Darman, as consultants, advisors, and executives. During Carlucci’s tenure at BDM, the company greatly expanded the number of contracts it had with the U.S. government; by 1994, the company had revenue of $774 million, up from the $295 million the company grossed in 1991, the first full year that the Carlyle Group owned the company.The strong links between the U.S. government and many of the private military companies that contract with them has presented questions regarding the revolving door between government and the private sector. In 1992, the Pentagon, then headed by Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, paid Brown & Root Services $3.9 million to produce a classified report detailing how private companies could help provide logistics for American troops in potential war zones. Later in 1992, the Pentagon gave Brown & Root an additional $5 million to update the report. Brown & Root (now called Kellogg Brown & Root, or KBR) is a subsidiary of Halliburton Corporation, which Cheney, the U.S. vice president, headed as CEO from 1995 to 1999. Brown & Root was also awarded contracts in 1995 and 1997 to provide logistical support in the Balkans, where the U.S. military has been enforcing the 1995 Dayton Peace accord that ended the war in former Yugoslavia. Those contracts mushroomed to $2.2 billion worth of payments over five years, according to the General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress.

Wall Street has noticed the booming business of both foreign and domestic PMCs. Security companies with publicly traded stocks reportedly increased in value at twice the rate of the Dow Jones industrial average in the go-go 1990s. Revenue from the global international security market was projected to rise from $55.6 billion in 1990 to $202 billion in 2010, an estimate that has risen sharply since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. The stock of guard providers Wackenhut Corp. rose 26 percent between Sept. 10 and 17, while that of Armor Holdings Inc., which provides a wealth of products and services for the military and law enforcement, traded at 31 times its 2002 projected value. Fortune magazine named Armor Holdings, a Florida-based conglomerate, one of “America’s 100 Fastest Growing Companies” in 1999. The company specializes in security products and services with myriad subsidiaries involved in everything from bulletproof vests and fingerprinting powder to computer security systems and landmine reduction services.

Like the defense industry generally, the trend among PMCs has been toward mergers, acquisitions, and consolidation. In August 2001, Armor Holdings acquired O’Gara-Hess & Eisenhardt Armoring Company, the world’s largest armored transport provider, boosting its 2001 earnings to $292 million. L-3 Communications, which has nearly $2 billion in annual revenue, was formed in April 1997 with the purchase of business units that were spun off after Loral Corporation and Lockheed Martin merged in 1996. L-3 Communications bought Military Professional Resources Incorporated (MPRI), which consults for and trains armed forces around the world, in July 2000.

As the industry continues its rapid growth, foreign governments are trying to figure out how — or if — to regulate it, thereby deterring PMCs from becoming vehicles for clandestine foreign policy, arms trafficking, or simply waste and mismanagement. The United States and South Africa are the only countries that exercise some regulatory oversight of domestic PMCs; other governments have acknowledged the need for the services PMCs offer, but have yet to develop a structure to oversee them.

In early 2002, the British government’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office released a report titled “Private Military Companies: Options for Regulation.” The report argued that PMCs could actually aid in low-intensity conflicts and proposed regulating them as soon as possible rather than leaving them to operate unchecked. The British press, however, had a field day with the notion that “mercenaries” would take the place of blue-helmeted U.N. soldiers, and a public outcry ensued. The report also pointed to the United States as the only place in the world where PMCs have become “major military corporations,” effectively licensed for over two decades “without apparently giving rise to major problems.”

A ‘national resource’

MPRI – headquartered in an office suite that looks more like a Fortune 500 company than a military command center – is located in northern Virginia, home to the Pentagon and the galaxy of defense-related companies that orbit it. Portraits of MPRI’s founders and CEOs in uniforms decorated with the stars and bars denoting the highest ranks of the U.S. military line the office walls. President Carl Vuono served as army chief of staff from 1987 to 1991 and oversaw the U.S. invasion of Panama and the Gulf War; Harry E. “Ed” Soyster was the former head of the Defense Intelligence Agency; and Crosbie Saint was the former commander of U.S. Army Europe.

MPRI was founded in 1988 as a military training consultancy by three generals who found themselves retired years earlier than they expected. “The concept was that there’s a national resource in retired military people,” Soyster told ICIJ. By providing training privately, MPRI’s founders saw themselves as freeing scarce infantrymen for combat. The company grew to become profitable in a couple of years and, in May 2002, MPRI reported annual sales of $95 million. According to MPRI’s Internet site, the company employs 700 people and has more than 12,000 former servicemen from the military, law enforcement and other fields available on a contract basis. The company’s first customer was the Defense Department, which hired MPRI to staff a colonel’s training course, and its business still consists largely of defense contracts for training and support services.

According to Soyster, as the Cold War ramped down, the company saw another potential market in former Warsaw Pact states trying to move toward NATO aid and membership. After seceding from Yugoslavia, Croatia approached MPRI to restructure its military. “They literally came to us and said, ‘we know what we want but we don’t know how to do it because we’re a bunch of Communists,'” Soyster said.

The MPRI contract with Croatia, signed in September 1994, was one of the first training contracts between a modern PMC and a foreign government, Soyster boasted. It turned out to be a mixed blessing for the company. The United States had wanted to restrain Serb-led Yugoslavia without a messy U.S. military commitment and saw a reinvigorated Croat military as essential to that goal. MPRI officials said at the time that the company’s contract was simply to teach the Croatians Western military principles and that tactical training was not included in the plan. In August 1995, less than a year after MPRI moved in, the Croatian army launched a lightning offensive that recaptured Serb-held enclaves of Croatia – a battlefield success the Croats had been unable to achieve in the previous four years. The Croat offensive led to further military action by the neighboring Bosnians against Serb-held positions that ultimately resulted in peace talks ending the Yugoslav war. But the military push forced more than 150,000 ethnic Serbs from their homes and left an “ethnically cleansed” Croatia.

A 1996 report by a U.S. congressional subcommittee found that the Clinton administration had encouraged Croatia to allow arms from Iran and other countries to transit its territory in violation of a U.N. arms embargo in order to bolster beleaguered Bosnian forces. Congressional investigators looked into MPRI’s role in the region, but their final report, much of which remains classified, said there was no evidence to back up European accusations that the U.S. government directly contributed military intelligence and weapons to the Bosnian army.

Soyster denies that MPRI acted under the tacit direction of the U.S. government in the Croatian deal. “We went over and taught democracy transition because that is what (the Croatians) wanted. They didn’t ask us to do anything else, and we wouldn’t have risked the reputation of this company to give that,” he said.

MPRI’s operations became controversial again in 1999, when the State Department temporarily suspended its contract to equip and train the Bosnian army, a program outlined in the 1995 Dayton Peace accord. News reports attributed the suspension to concerns that weapons from the program were being diverted to Muslim guerrillas in the neighboring Serbian provinces of Kosovo and Sandzak.

In addition, a number of British companies have moved to expand operations and set up shop in the United States. London-based TASK International, which cites its niche market as the training of military and police forces, recently established an office in Miami – a move, the company’s director of operations explained, to handle contracts the company holds in the Caribbean. The company is currently training the Jamaican police and in the past has trained the presidential guard in Nigeria, the royal police in Malaysia and the special forces of the United Arab Emirates.Far away from the corporate office of MPRI, dozens of small companies across the United States are quietly offering downscaled versions of military training, according to ICIJ’s investigation. Even smaller outfits are going global, establishing offices and training centers in multiple countries or boasting of the ability to send mobile training teams anywhere in the world. The Nevada-based Sayeret Group says it has tactical teams that can deploy to anywhere in the world in support of security, protection and direct action operations. Pistris Inc., a Massachusetts-based maritime security company which maintains its own fleet of vessels, also claims it can provide fully equipped, mobile protection teams to provide waterborne security of oil fields, ports and vessels throughout the world. Trojan Securities International, a company established by former British military and American law enforcement, maintains training centers in Arkansas, where the company is based, as well in Ecuador to accommodate the company’s work in Latin America.

Though these groups may seem marginal, several have received new, multimillion-dollar contracts from the U.S. government since Sept. 11.Blackwater Lodge of North Carolina, Surgical Shooting Inc. of California and Automation Precision Training of Virginia were awarded contracts worth more than $60 million by the U.S. Navy in September 2002 for military training.

Many of these companies also train foreign clientele, both abroad and at their U.S. facilities. Ground Zero U.S.A., based in Marion, Alabama, lists an international training schedule for 2002 that includes programs in England, Scotland, Ireland, Mexico, Canada and Norway, and Sayeret can provide a mobile training team to travel to any location in the world at the client’s request, according to Sayeret Group President Duke Piper. Piper told ICIJ that the company takes special care to vet clientele and works closely with an investigative firm that runs background checks on all prospective clients. Though he declined to divulge what foreign clients the company has trained since its founding in 1991, Piper said Sayeret had recently worked with Philippine law enforcement personnel.

While Piper believes self-regulation within the industry is necessary, he admits that little oversight currently exists for those who choose to bypass the licensing system. “There are no regulations or laws saying you have to do X, Y, Z. It’s more of an integrity or ethical issue that comes into play,” Piper said, adding that “some people do choose to operate behind the scenes or under the table.”

Underwhelming oversight

Though the U.S. system for licensing PMCs was constructed to prevent exactly those kinds of operations, oversight of the process – and of the contracts themselves – is far from comprehensive. Defense services, including training, are considered military products under U.S. law, and their overseas sales are regulated just like American-made guns or tanks. The International Traffic in Arms Regulations Law (ITAR) requires PMCs to obtain approval from the State Department before selling their services to a foreign government. State’s Office of Defense Trade Controls reviews contract proposals to ensure they do not violate sanctions or other U.S. policy.

However, PMCs can also sell their services abroad through the Defense Department’s Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program, which does not require any licensing by State. Under FMS, the Pentagon pays the contractor for services offered to a foreign government, which in turn reimburses the Pentagon. Vinnell’s contract to train the Saudi Arabian National Guard and MPRI’s contracts to train the Macedonian and Bulgarian militaries came under the FMS program. Steve Schooner, a government contract expert and law professor at George Washington University, said companies will often seek FMS support in order to avoid the lengthy ITAR licensing process and gain the backing and stability of the U.S. government.

The politics inherent in the licensing process subject it to lobbying from companies and government entities, alike. Through corporate consolidation, some PMCs also have gained considerable resources to work the licensing process. For example, MPRI now has the power of L-3 Communications’ substantial legal department behind it. And sometimes, one department of the government will lobby another on behalf of a PMC. An April 2001 Pentagon memo, obtained by ICIJ, noted that MPRI “may need our help or moral support in getting the … license from State,” necessary for the company’s proposed contract to train military forces in oil-rich Equatorial Guinea, which the Pentagon memo referred to as the “Kuwait of the Gulf of Guinea.”

Soyster acknowledged that MPRI’s applications for overseas export licenses include descriptions of how the company’s presence in a given country would benefit U.S. interests. Charles Snyder, the deputy secretary of state for African affairs, said that in reviewing licenses, such as MPRI’s proposal for Equatorial Guinea, his staff considers the contract’s value to U.S. policy in the region. “We can see some merit in using an outside contractor, because then we’re not using U.S. uniforms and bodies,” he said. “A country like Equatorial Guinea is going to get [training] from somewhere, so we’d rather have U.S. contractors on the ground. That way at least we’d have feedback from professional trainers as to whether this is having any impact or not.”

Under ITAR, Congress must be notified of all defense services contracts worth more than $50 million, though in practice, the State Department generally submits all potentially contentious applications to Congress, said Douglas Johnson, spokesman for the department’s Office of Defense Trade Controls.

The public, however, has little if any chance for a glimpse into the reach of PMCs. The Arms Export Control Act – which ITAR amended – still stipulates that the names of countries and types of defense articles involved in each contract “shall not be withheld from public disclosure unless the President determines that the release of such information would be contrary to the national interest.” According to Johnson, State Department lawyers have interpreted the clause to mean that all information outside of a list of countries and defense articles should be withheld. Therefore, the only information available to the public about contracts between a private U.S. military company and a foreign government is which country the contract was performed in and what services were exported – and then only through the Freedom of Information Act. (In May 2002, the Justice Department issued new guidelines allowing companies to challenge the release of information about them to the public under the Freedom of Information Act, further hindering public disclosure.)

After contracts are approved, oversight is weak. The General Services Administration maintains a list of companies barred from doing business with the government, but no single government-wide agency monitors the performance of companies that do get contracts. Schooner, the federal contracts expert, said that while government agencies began using performance evaluations of outside contractors six years ago, implementation is “spotty at best.”

The Defense Department tasks several different agencies with oversight, depending on the type of contract. In the Balkans, for example, agencies responsible for contracts include the Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army Europe, Defense Contract Management Agency, Defense Contract Audit Agency and Army Task Force Commanders. A May 2002 GAO report that looked at extra costs incurred in 2001 by the Defense Department’s overseas contingency operations found that no one in the Defense Department knew the number of contractors in the Balkans, what they were contracted to do or the government’s obligations to them.

Oversight is further weakened, according to Schooner, by the increased use of “cost-type” contracts, in which the government pays the contractor a base amount, along with additional fees for services that are often initiated by the contractor and later approved by the government.

A September 2000 GAO report found that effective oversight of Brown & Root’s contract in the Balkans was impaired by the government’s confusion about its authority over the contract and insufficient training of Army auditors, among other things. The report also found that although the Army had a process in place to review Brown & Root’s requests for “new work” or additional services – which comprised more than 90 percent of the fees paid under the contract – the requests were approved but not routinely reviewed. Between 1996 and 2000, the GAO estimated that Brown & Root collected more than $2.1 billion in additional costs, which nearly doubled the amount agreed to in the original contract. Brown & Root called the GAO criticisms “subjective opinion.”

In February 2002, Brown & Root paid $2 million to settle a lawsuit filed by the U.S. government that claimed the company inflated prices for maintenance and repair work at the Fort Ord military installation in Monterey, California. Brown & Root denied any wrongdoing and said it settled the suit only to avoid further litigation. In a review of nearly a dozen private military company contracts, ICIJ found that the contractors frequently were tasked with creating their own performance evaluations. In its multiyear contract to provide simulation exercises for U.S. troops in Europe, Logicon, an information technology company owned by defense giant Northrop Grumman, was required to prepare a “Quality Control Plan” laying out evaluation processes. DynCorp’s contract to provide security guard services for U.S. Army installations in Qatar required the company to create a quality control program that, while mandating regular meetings with the government, contained “processes for corrective actions without dependence on government direction.” The contract also licensed DynCorp employees to use deadly force and gave them access to classified information.

‘Winners and losers’

Despite scandals and poor reviews, the contracts keep piling up.

Amid the government lawsuit against Brown & Root – and the critical GAO report – the Army awarded the company a 10-year contract in December 2001 to provide base-support work overseas under its Logistics Civil Augmentation Program, or LOGCAP, the value of which could run into the billions of dollars.

Some of MPRI’s overseas ventures have produced unsatisfied customers. In Colombia, the company was contracted in 2000 to help restructure the Colombian military as part of Washington’s war on drugs. But Colombian defense officials called the training useless and said MPRI advisors had “reinvented the wheel,” noting that no one on the company’s staff in Colombia spoke Spanish. Reportedly under pressure from Colombia, the Pentagon did not renew the one-year contract. Pentagon officials publicly backed the company’s performance, and Soyster told the St. Petersburg Times that MPRI had fulfilled the requirements of its $4.3 million contract.

In Macedonia, where MPRI has been operating since 1998 as military advisors for the Macedonian armed forces, the army chief of staff lambasted the company’s reforms in a July 2002 interview with a local newspaper as “catastrophic mistakes” that created military units only on paper.

In Nigeria, where MPRI was tasked to overhaul the Nigerian military, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Victor Leo Malu questioned MPRI’s proposal to cut almost a third of the armed forces as well as the motives behind the company’s request for sensitive documents and information.

Soyster attributes much of the dissatisfaction to those who might find themselves on the outside of MPRI’s suggested reforms. “There are winners and losers if you make changes, and (Malu) could have been a loser,” he said of the Nigerian general, who was later replaced as army chief of staff.

DynCorp, another recipient of sizable contracts, was caught in a scandal in 2000 when two employees deployed on the company’s $15 million annual contract for logistical support in Bosnia and Kosovo alleged that several of their colleagues had colluded in the black-market trade of women and children. DynCorp later said the company did not tolerate such behavior and fired those accused of the offenses. According to media reports, DynCorp also fired the employees who made the allegations for unrelated charges, including allegedly tampering with time cards. Both sued the company for wrongful dismissal, and an employment tribunal in Britain, where one suit was filed, ruled in August 2002 that the dismissal was unfounded and retaliation for the disclosures. A DynCorp spokeswoman said the company planned to appeal. The other suit was settled out of court soon after.

Defense contracts are among the government’s most expensive and numerous, and the companies that win them among the country’s largest – companies that legislators don’t want to alienate. A review of lobby documents from 1995 to 2001, obtained by ICIJ, shows that PMCs take a strong hand in their futures through lobbying. Wackenhut, Brown & Root, Booz Allen Hamilton, Betac Corp., Armor Holdings, Logicon and Cubic Corp. have all employed lobbyists to advocate for their interests on Capitol Hill. Most lobby on Defense Department appropriations and national defense authorization bills, the major spending legislation for the Pentagon. In addition, Betac lobbied on intelligence authorization bills, Logicon on outsourcing of government programs and Armor Holdings on “foreign relations for export of products.”

These companies are often the only ones capable of providing the large-scale and complex services and products the military needs. A factor is the change in the nature of warfare: in the United States, fewer individuals are doing the actual fighting, while massive support systems are required to maintain the world’s most modern forces. The requirements of high-technology warfare have dramatically increased the need for specialized expertise, which often must be drawn from the private sector. In Afghanistan, for example, contractors from Northrop Grumman were hired by the Air Force to man Global Hawk, the newest and most advanced surveillance plane, because they designed the unmanned drone and had the expertise to run the system. As a result, the line between frontline activities and logistical support is further blurred.

But small contractors also play a role. ICI of Oregon, with a permanent staff of just five employees (they contract additional employees as needed), reported annual sales for 2001 of $8.8 million. The company was incorporated in 1994 by Brian Boquist, a Special Forces lieutenant colonel in the Army Reserve who is making his second run for a seat in the U.S. Congress. Boquist is also a former executive of a subsidiary of Evergreen International Aviation, a private air freight company based in Oregon that has reportedly taken on sensitive missions for the U.S. government.”There’s a view that if companies do bad things, that’s just too bad because the nation’s defense is more important than anything else and there are some firms we can’t not do business with,” Schooner said, citing high-tech weapons manufacturers as an example. “There’s a long-running tradition that the government tends to debar small and unimportant contractors because it can, and tends not to debar large important companies because it can’t – we need them.”

ICI has aided extremely risky peacekeeping operations in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Haiti, and evacuated peacekeepers, aid workers and diplomats from combat zones. In one instance, an ICI helicopter was dispatched from Freetown to a remote village in Sierra Leone to collect a senior Nigerian officer. But in the 30 minutes it took the ICI crew to reach the village, rebels had attacked and the helicopter came under anti-aircraft fire. “I said, someone is here, and they’ve got some heat, but where is my army?” a member of that ICI team said in an interview. “I could see we didn’t own the village anymore, and I’m about to be shot out of the sky. We drove [flew] up the road, looking for the guy we needed to get out. Then I saw 300 of our guys [Nigerians] running down the road in complete disarray, with their leaders in front.” The helicopter landed but was mobbed by the desperately fleeing soldiers and had to take off again, with men hanging from the helicopter’s doors and landing skids as it flew out under heavy fire.

ICI brings an unorthodox approach to the conflicts of the third world. For a start, its pilots fly in Russian helicopters and use Russian crew. One former ICI employee described the Russian Mi-8 helicopters as “damn ugly, but they’re tough as woodpecker lips – they fly and they keep flying.”

ICI – whose Web site boasts that the company was the “1998 U.S. Dept. of State Small Business Contractor of the Year” – also has been supporting a U.S. military training program in Nigeria. In addition, the ICI Foundation, a charitable organization founded by Boquist, developed a medical training program under U.S.-government auspices in southern Sudan, where Washington has pumped in at least $13 million in recent years in support of the rebel opposition. (DynCorp is another key contractor in southern Sudan.)

That a small company like ICI has been involved in so many operations is indicative of the changing nature of war. The lean military of the new millennium cannot be everywhere at once, so contractors fill in the gaps. That need grew exponentially when the Bush administration responded to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks with its war on terrorism.

The increasing scope of the war has led to a bonanza for PMCs. For example, ArmorGroup, the services arm of Armor Holdings, was hired by the British government to provide security for British embassies around the world after a diplomat was killed in a bombing believed related to the al Qaeda network. Kellogg Brown & Root has built camps in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for U.S. detainees and is providing logistical support for U.S. military bases in Uzbekistan. MPRI says it is supporting homeland security in the United States and hopes to be hired to train the newly constituted Afghan army.

Many worry, however, that the inadequate oversight system now in place will never be able to keep up with the sheer volume and geographical spread of the hundreds of Pentagon contracts being issued. The May 2002 GAO report predicted that weak oversight would remain a problem. “With the involvement of contractors in the efforts to combat terrorism, the potential exists for a similar condition (as in the Balkans) in Afghanistan and the surrounding area.” At the request of the Senate Armed Services Committee, the agency has begun a review of the oversight of defense contractors in deployment missions worldwide. That report is due out in mid-2003.

Samiya Edwards contributed to this report.

Join the conversation

Show Comments